Not every Arab television channel can boast of a launch party at the Armani Hotel in Dubai.

Indeed, Wednesday's star-studded launch of the MBC Drama channel at the Burj Khalifa was something of an exception. For this is an industry populated by an increasingly vast array of satellite TV channels, and an equally vast array of funding levels.

Of the 500 people on the guest list, 100 or so were stars of showbiz.

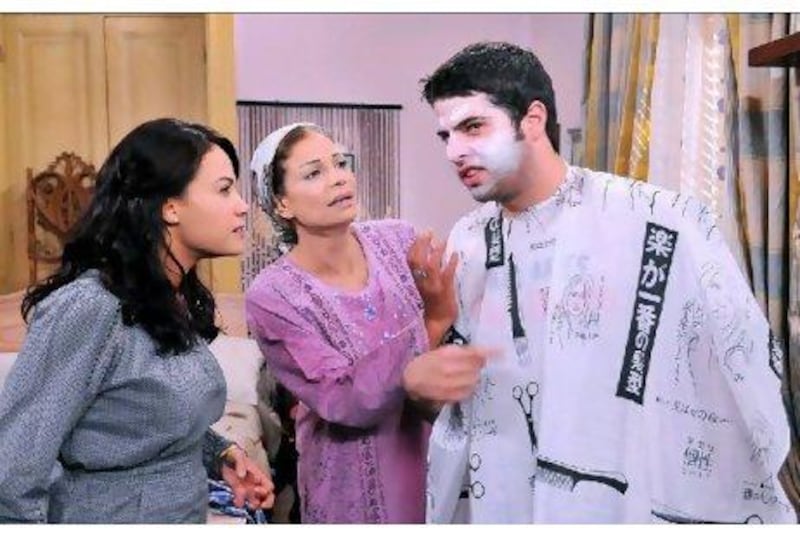

The Saudi broadcasting giant MBC Group is behind the new channel, which makes its first broadcast tomorrow. MBC Drama marks the 10th channel launched by the network, which is now approaching its 20th anniversary.

Yet the understated glamour of the Armani Hotel is not exactly the venue of choice for most channels in the region.

At the other end of the scale from the dominant MBC, there are small, independent TV channels, only a few of which are commercially viable. Many of these are run on a shoestring, or as vanity projects, or at a great loss.

For if MBC is an Armani-brand chaise longue, many other regional channels are like an old chair held together by bits of gaffer tape.

Consider the words of one executive based in the UAE, describing a visit to an independent news channel in the Middle East: "The set was, at best, rickety."

Oblique furniture-related comparisons aside, the Arab free-to-air satellite industry is certainly disparate.

The frenetic growth of the sector, driven by rising advertising spending during boom times, partly explains this scenario. According to the research firm Arab Advisors Group, there were 100 free-to-air satellite channels in the Arab world at the beginning of 2004. This had doubled by November 2005, and reached 370 less than two years later.

"The rapid increase in the number of free-to-air channels has been mainly due to the growth of advertising market that resulted in a large number of low-cost channels emerging," says Hadi Raad, a principal in the communication, media and technology practice at the consultancy Booz & Company.

"More flexible regulations in the Arab region have allowed the creation of channels (for example, call-TV channels) that did not previously exist. Moreover, a number of political channels, fully sponsored by political parties have emerged."

But since the advertising downturn, several analysts predicted the closure of underperforming TV stations.

The reasoning for this is that the dominant channels attract the lion's share of the audience - and therefore advertising revenue - while the smaller players miss out.

"The 80-20 rule applies: 80 per cent of the audience follow 20 per cent of the stations," says Jawad Abbassi, the founder and general manager of Arab Advisors Group. "Some of the channels get very little audience share."

Yet despite the warnings of some analysts, the total number of free-to-air satellite channels has continued to rise. There are 487 channels in the Arab world, of which about 80 per cent are broadcast in Arabic.

The rate of growth is, admittedly, slowing: more than 100 new channels emerged between August 2007 and March last year, while only another 13 stations launched up until April this year.

But the total number of channels is expected to rise further, probably to as many as 550, according to Mr Abbassi. "I don't foresee a drop in the free-to-air channels. I think it will stabilise at around 540 or 550," he says.

So in spite of other analysts' concerns, the TV landscape keeps expanding.

It is not surprising that there have been launches by established players such as MBC. Mazen Hayek, the official spokesman and group director of PR and commercial at MBC Group, says the audience of MBC Drama "will eventually reach millions". That is "a real incentive for all drama producers", he says. "They have a platform to air and reach a greater market."

But MBC is an exception to the rule.

Almost 30 per cent of the free channels are government-run. These are "not driven by profit or loss", says Mr Abbassi. It is for this reason that there has not been "a shake-up and consolidation" that many analysts predicted, he says.

Among the 70 per cent of channels that are privately run, there have been closures and new entrants. "These are the ones which you see going out and being replaced by others," he says.

But there is genuine growth in the number of "niche" channels - the kind that do not attract such large audiences, but can still be commercially viable.

Ahmad Kargar, the managing director of the independent fitness channel Physique TV, which is broadcast as a free-to-air satellite channel across the MENA region, acknowledges that some TV channels have closed. "There are always about 100 channels who have started airing but with no effective business plan. So every month some people are added to this list and some are going off air," he says.

But Mr Kargar adds that the number of channels geared towards a specific demographic is growing.

"Channels are getting more and more niche. One might not be able to start a music channel any more, as there are tens of those channels with little revenue to share," he says. "But niche channels are enjoying growth as their audiences are specific, and advertisers can make sure they are getting to the right consumers easily."

Mr Kargar points to changes in the delivery of TV channels - such as internet protocol TV and set-top boxes - as being likely to herald change in the free-to-air landscape. The advantages of such technology is that they allow for better targeting of households, whereas satellite-TV operators know comparatively little about their audiences.

Yet Mr Abbassi says the free-to-air satellite network "will remain vibrant in the region", pointing to an opportunity for more channels being produced by the private sector. "Maybe one channel wants to attract an audience of 5 to 6 per cent," he says.

And so, the growth in number of Arab TV channels looks set to continue. Shame about the rickety furniture, though.