Special economic zones are back in fashion across Africa as countries scramble to replace revenue lost from falling commodity sales.

According to the Africa’s Pulse, the World Bank’s twice-yearly analysis of economic trends published last month, economic activity in Sub-Saharan Africa slowed in 2015 to its lowest rates since 2009. GDP growth averaged only three per cent, down from 4.5 per cent in 2014.

With lagging commodity prices driving the downturn, many countries are looking at special economic zones (SEZ) with a renewed sense of urgency.

It is not hard to see why. SEZ’s provide specific geographic locations that are usually immune to host country’s laws regarding import duties, labour relations and local partner requirements. These incentives lure businesses to set up operations that they otherwise might not consider relocating. Over time, they help the host country to diversify its economy.

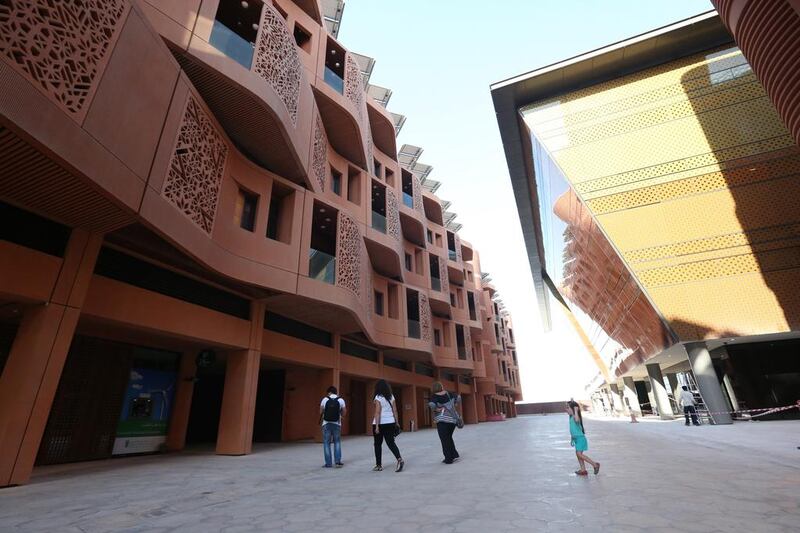

SEZ’s have been a central theme in the UAE’s development, such as Abu Dhabi’s Masdar Free Zone used to attract investors that are helping move the economy away from oil dependency. Across the UAE, 21 such zones have drawn 20,000 businesses to the Emirates, a global success story for the concept.

Many sub-Saharan states that have enjoyed years of unprecedented growth as the world sought their raw minerals are now hoping to use SEZs to the same purpose.

One such is located in East London on the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa, where the results are paying off. Up to three international motor manufacturers are considering moving in to begin building vehicles to sell across Africa and beyond.

“Suddenly we are getting more interest from companies,” says the chief executive of the facility Tembeli Zweni. “They will save on start-up costs because we would have this huge facility.”

The facility already houses component manufacturers that provide parts for local manufacturers already present in South Africa such as BMW, Ford and GM. South Africa has the continent’s only car making industry, and has about eight manufacturers in all.

While the three newcomer car companies have yet to be named, they are believed to be Asia-based. A feature of SEZs is that they are often industry specific, allowing investors to pool manufacturing resources. The East London SEZ is working toward providing a single-vehicle paint shop, says Ryan Bax, an Industry Analyst at Frost and Sullivan in Cape Town. Spray coating is a complex and costly process and a paint shop can cost up to US$100 million, he says.

In spite of the general economic downturn, the long-term prospects for Africa as a whole were good, Mr Bax says. “Vehicle manufacturers are quite bullish on Africa, and are looking at the long term picture.”

Sooner or later countries south of the Sahara will see an economic recovery, and with it, a demand for vehicles.

“Manufacturers are not really looking at South Africa where the outlook is flat but to the rest of the continent were growth is still happening,” Mr Bax says.

Instrumental in SEZs opening up across Africa is the influence of China, where such zones have underpinned the country’s spectacular growth over the past two decades.

In Zambia, the Chambishi SEZ was developed largely with Beijing’s help and today has more than 43 firms representing a $1 billion commitment, according to the Zambian ministry of commerce, trade and industry.

Nigeria’s Lekki Free Trade Zone in Lagos was also largely underpinned by Chinese investment and expertise, and it too has close to $1bn of investments.

In Ethiopia, the Huajian Shoe Manufacturer from China set up two production lines that can produce 2,000 pairs per day, for export to the United States and European markets.

Many more, too, are on the way. Of Africa’s 54 countries, most have SEZs or are planning them.

However SEZs are not a guarantee of success, especially as competition between them increases.

“Development cannot be simply imported,” says Yejoo Kim, a research fellow at the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University near Cape Town.

“The host government is the most significant actor, creating a business friendly environment and setting up institutional arrangements that can attract investors. The Chinese government was successful in this regard and that is what African countries should learn.”

Even as China is the standout example of this model, the country is also experiencing difficulties that show the limitations of SEZs, Ms Kim says.

In trying to spread the economic benefits they have brought to coastal cities, Beijing has allowed inland regions to open their own zones.

“So SEZs are mushrooming all over in China. This competition can result in a race to the bottom. Countries and cities have to provide incentives such as tax exemption, free land, electricity and water, a cash grant and so on in order to attach investors,” Ms Kim added.

As they chase investors with ever more generous benefits, these zones can cannibalise a dwindling pool of capital and often provide little by way of return for the community that sets them up.

Apart from growing competition, Africa has another enduring problem to any economic endeavour – lack of infrastructure. This adds to the economic burden of developing such zones to standards expected by investors. Nigeria has, frankly, terrible electricity infrastructure and the Lekki zone had to install gas-powered generators to ensure an uninterrupted power supply.

Difficulties aside, for many African countries there is little alternative to the SEZ model. Angola has gone from one of Africa’s best-performing economies to one of the worst.

Last year it signed legislation that will pave the way for a SEZ. Landlocked Uganda, too, has started luring investors to its own hub and recently signed the Turkish industrial conglomerate ASB Group as an anchor tenant.

In the race to economic diversity, SEZs are probably the only viable option for Africa.

business@thenational.ae