The powerful current forces its way down the riverbed and past the sandbanks, pushing the boat bobbing on its restless waters towards alternate banks of the great river. The trees lining the shore frame the pacy ride with a relentless green.

Suddenly a flame pierces through the wooded expanse, drawing attention to a cluster of low-rise buildings. A gas flare is burning off the side product of oil production - and visitors to the Yasuni National Park in Ecuador realise this idyll is no longer untouched.

In popular imagination, the major sources of oil are the wells plunged into the sands of the Middle East's deserts, or platforms that tower majestically above the ocean.

The reality is often very different. Much of the world's crude is derived from the steamy rainforests that cover the Latin American plains.

Ecuador holds Latin America's third-largest known oil reserves and pumps the bulk of its 500,000 barrels per day from an area known as theYasuni, or the "sacred land".

Ecuador's ecological richness is primarily associated with the Galapagos Islands, made famous by the work of the 19th-century British evolutionary scientist Charles Darwin. Yet, located at the intersection of the Amazon, the Andes and the Equator, the national park is home to almost unparalleled biodiversity.

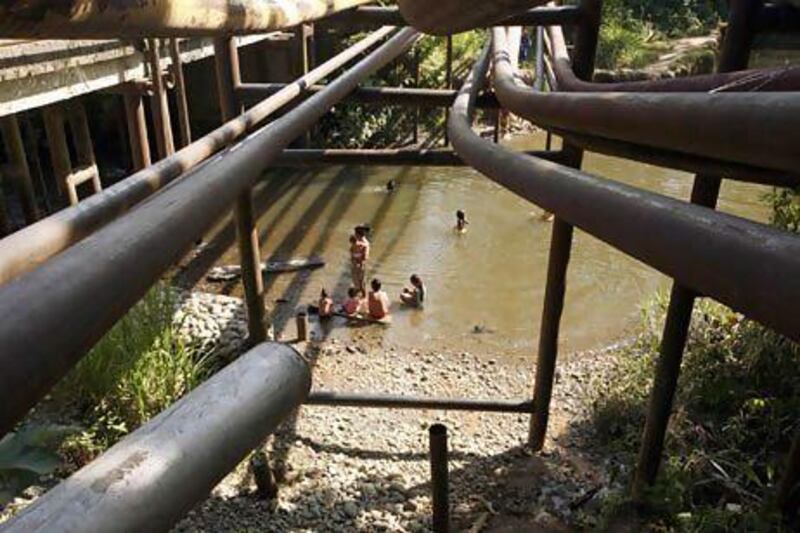

The vast forests of the Yasuni are already riddled with the manifestations of an active oil industry. Six companies are pumping oil in the national park and roads, pipelines and processing facilities scar the once-pristine landscape.

The sight of huge flames of flared natural gas rising above the vegetation is sufficient to wrench the hearts of environmentalists, but the Yasuni is no ordinary rainforest, say those who know it well.

"It's one of the most incredible places I've been to and I've travelled a lot. Every time you go out of the forest you see something new," says Bette Loiselle, a professor from the University of Florida who has done field work in the park for several months every year since the turn of the century.

One hectare of the park's wet and leafy forest contains more tree species and as many different insects as the whole of North America, for instance.

The area was spared the effects of climate change during the Ice Age, preserving its wildlife and acting as a refuge, and new varieties of mammals, fish and insects are discovered on a regular basis.

Yasuni's rivers are home to almost 400 different types of fish, providing a rich hunting ground for the rare river dolphin and more frightening predators such as the electric eel.

The delicate dance

The government in the capital Quito relies heavily on oil receipts to fund extensive social programmes and subsidies. The president Rafael Correa's re-election last month is in no small part thanks to the windfall resulting from high oil prices.

The left-leaning president was a close ally of the former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and is thus viewed with suspicion by the United States. But his largesse has made him popular with the electorate, which has extended his term in office for a further four years.

Oil is central to the president's agenda and it was a highly unorthodox decision by Mr Correa to promote a conservation project that will involve Ecuador forsaking a good part of the oil wealth buried under the Yasuni national park if international funding of its renewable energy sector materialises.

While much of the national park has been marked by oil exploitation, one area remains untapped in spite of its rich potential: the Yasuni ITT block contains some 846 million barrels of proven oil reserves, distributed in the Ishpingo, Tambococha and Tiputini oilfields that make up the block's acronym. This amounts to about a fifth of Ecuador's reserves. Probable reserves are estimated to be as large as the proven oil pools.

In spite of the mouthwatering prospect of boosting oil revenues, Mr Correa early on in his reign decided to try to spare the block from exploitation, and instead bring to life the Yasuni ITT initiative. The project relies on receiving US$3.6 billion (Dh13.22bn) from international donors by 2024 and governments, companies or individuals are welcome to contribute.

It is a delicate dance for the president.

"Correa often times navigates on two waters: his idealism and the practical need his revolution has for resources to keep up with his ambitious public expenditure plan," says Ana Maria Correa, a political analyst at the consultancy Prófitas, based in Quito.

There are no indications that the government is going to rein in its spending programme, and fiscal needs could triumph over environmental concerns.

"They have been successful in raising tax revenue, but if they are going to continue to spend at current levels oil is an essential source of revenue," says William Lee, an analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit. "Its going to be challenging to have this big untapped resource lying around."

International support

The project has the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which is administrating the trust fund that was created for the initiative late in 2010. Donors of $50,000 or more are issued with guarantee certificates, in which Ecuador's government pledges to return the donation in case it reneges on its promises and taps the ITT reserves.

Yasuni ITT is a bold and novel approach to conservation, and shows undoubted government commitment. The target sum is not only half of what the block's crude would fetch at 2007 prices, Ecuador would also receive significantly higher revenues for it at current market prices.

"[The oil price] is much higher at this point. They are willing to sacrifice that if the international community comes up with those $3.6bn," says Gabriel Jaramillo, a UNDP programme specialist who leads the organisation's trust fund efforts in Ecuador.

In return, the trust fund is designed to accelerate the country's transition towards renewable energy.

Already, Ecuador derives more than 60 per cent of its electricity from alternative sources such as hydropower and the aim is to increase that portion to up to 95 per cent by 2016, according to Professor Carlos Larrea at the Simón Bolívar University in Quito, one of the masterminds behind the initiative.

Donations going into the trust fund, also known as the "capital fund window", will be pumped into renewable energy projects as loans with an expected return of 7 per cent.

The interest from the loans will be paid into a so-called "revenue fund window" that will provide funding for conservation, social development of the country's indigenous tribes as well as research and development. The fund is, in effect, a foreign-sponsored sovereign wealth fund for national development.

Net avoided emissions

The Yasuni initiative is based on a broader concept of climate change mitigation, which the government has termed net avoided emissions.

Under this approach, developing countries could get paid for leaving hydrocarbon reserves untouched, while at the same time preserving a rich biosphere.

Mr Correa has endorsed the idea internationally, presenting it to the UN soon after becoming the president in 2007. His diplomats floated the idea again during the climate change negotiations in Durban and Doha.

"We are trying to create a particular space for Yasuni to become part of the multilateral system," says Daniel Ortega, the director for environment and climate change at the foreign ministry.

The concept is not dissimilar to efforts to protect the rainforest through the reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation programme, known as Redd, that is promoted by the UN.

But the forest conservation programme has yet to be integrated into UN climate change efforts and the Yasuni initiative will have to raise its fund without the help of an international framework, says Mr Jaramillo.

"I think many countries are waiting for issues such as Redd and many other issues to be settled before they can bring another proposal to the table," he adds.

The net avoided emissions concept has been met with scepticism by oil producers and traditional donor countries and has posed a problem for those seeking funding for the project.

"[For] the members of Opec, the Arab countries, the money cannot go for the non-extraction, because then they'd be agreeing that oil contaminates," says Ivonne Baki, the secretary of state for the Yasuni ITT initiative.

Donors such as Germany and Norway have also voiced concern, with the latter fearing oil exporters such as Saudi Arabia could start claiming compensation for reducing their production.

The people behind the initiative are keen to allay such fears.

"According to our proposal, the only place in which this mechanism can be replicated are biodiverse countries," says Prof Larrea. He believes other Latin American countries with large rainforests and Asian countries such as Malaysia could legitimately take Yasuni as a blueprint for conservation efforts.

Germany, a nation that cherishes its own forests, has been critical of the initiative. Dirk Niebel, Germany's minister for development and international cooperation, has dismissed the Yasuni fund as "giving money for doing nothing", before committing $50 million for investment in specific conservation projects in the national park.

Mr Niebel's remarks have caused irritation in Quito.

"The non-extraction of oil is an environmental service provided, so we have to get rid of the idea of paying for nothing," says Mr Ortega.

International scepticism may be irksome but the initiative has been pragmatic. Germany's contribution, while not committed to the capital window, is still counted towards the final target sum of $3.6bn.

So far, the vast majority of the roughly $330m in pledged contributions have not been into the fund itself, as the capital window has so far only attracted about $8m.

This may prompt a change in the marketing pitch.

"It's being discussed at the moment to strengthen the biodiversity function of the ITT initiative, to strengthen the social bit instead of focusing only on the net avoided emissions part of it," says Mr Jaramillo.

The allocation of capital is also under revision. The money currently available has been pledged towards a hydroelectric dam, funding the entire project.

Mr Jaramillo feels this is not the best use of resources and in future the fund could provide no more than a fraction of the project financing as seed capital, with private investors making up the shortfall. Generous tariffs for solar energy will help to attract private money.

The Yasuni ITT initiative sprang into life at the end of 2010 and has been campaigning for funding internationally only since the beginning of last year. While the haul over the past two years has been far short of the annual amount of donation needed to meet the target, there is optimism about the growing awareness of the project abroad.

Already, Yasuni has been on the cover of National Geographic this year and efforts are being stepped up to publicise the initiative in the international press and to make use of the marketing potential of the internet.

"The campaign to start raising money from the social networks will start this year," says Mrs Baki.

Government-level campaigning will not be neglected.

Discussions with the Arabian Gulf states are continuing, and Ecuador hopes to receive money from the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, whose contributions for alternative energy projects will be dispensed with the help of the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena).

Mrs Baki, who has family ties to the Middle East and counts Qatar's deputy prime minister Abdullah Al Attiyah as a childhood friend, has toured the Arabian Gulf to drum up financial support for Yasuni. She hopes Doha will be the first to contribute, setting an example for others.

"I think if one gives, then the others will follow," she says.

Yasuni is an example of the prominence of oil production and its effect on nature in Ecuador's political discourse. Mr Correa has not been shy to cast this theme into the international limelight and in the 2010 climate change negotiations in Cancún, Mexico, he proposed a tax on each barrel sold by Opec members.

Opec is studying the proposal, says Mrs Baki, which could lead to the creation of a new fund next to the existing Opec fund for international development. If only a few cents for every barrel is set aside, it would provide for 80 per cent of the money needed to combat climate change, says Mr Ortaga.

"We can talk about climate change, how to mitigate it and how to adapt to it, but until we know where the money to finance those activities will come from, [these] are essentially [just] good intentions," he says.

With the Yasuni ITT initiative, Ecuador has put words into action. The government will now have to work hard for the international support needed to turn its bold idealism into reality.