One of the curious – or not so curious – features of the critical response to Martin Amis's work is how quickly it turns personal. You can practically guarantee that at least half the reviews of this bumper assemblage of occasional journalism will begin with an anguished reminiscence of how the reviewer first stumbled upon Money (1984) in a university bookshop and read on, enraptured, until the final page was reached.

That this anguished reminiscence should sometimes end in a volley of complaints about the modern-day Mart, his life, opinions and domicile, is thoroughly understandable and in some ways entirely necessary. We grew up with Mart, us white, male, British 50-somethings; his were the books we read when we were young, and it pains us beyond measure when he lets us down. If there is a fair amount of letting down on display here – together with some absolutely A-grade literary journalism – then several of the volume's imperfections are to do with the genre in which it reposes. After all, it takes a very seasoned practitioner put to work over a three-decade stretch not to repeat him or her-self or to return with a kind of homing instinct to the subjects that set his pulse a-flutter.

Then again, even the most prodigious talent eventually finds itself writing at different levels and for different audiences, offering high seriousness about religion and terrorism in The Wall Street Journal and low(ish) comedy about (mis)adventures on the tennis court in The Guardian.

There is no getting round these calibrations, but to read the results en masse can sometimes lead to bewildering shifts in perspective – from the California pornography industry, let us say, to the 1999 Champions League final in a couple of high-octane pages.

Mart has always kept a weather, and with the exception of tennis, non-practising eye on sport, here represented by essays on Diego Maradona's memoirs and some highly astute reflections on the 'personalities' of Wimbledon. That aside, The Rub of Time can be divided into three main categories: the personal, the political and the literary. In category one, you notice straightaway the presence of a tendency that has barrelled its way through Mart's autobiographical writings for at least 20 years, which is to say its defensiveness. A piece entitled The Fourth Estate and the Question of Heredity laments the UK media's obsession with his and his family's affairs, while He's Leaving Home, a 2012 article for the New Republic about his relocation to New York, protests at the assumption that "I was leaving because of a vicious hatred of my native land and because I could no longer endure the well-aimed barbs of patriotic journalists".

That some of these assumptions about Mart and the kind of person he is were also shared by readers is confirmed by the authorial Q&A sessions conducted for British newspapers that he bravely reprints (sample questions: "Do you ever worry you have inherited some of your father's misogyny?"; "Why are you such a snob?"; and "How do you think you might have ended up spending your working life if your father hadn't been a famous writer?") As for the second allegation, if you define snobbishness as "judging by arbitrary criteria" then its only real victim here is Jeremy Corbyn, pinioned for the "up-to-date vulgarity of his syntax", possessing two poor A-Levels and belonging to a part of the 1970s left-wing demographic first encountered during Mart's apprentice years at the New Statesman ("There were identikit Corbyns everywhere – right down to the ginger beard, the plump fountain pen in the top pocket, and the visible undervest, slightly discoloured in the family wash.")

Not, of course, that any of this is of the slightest interest, for as Amis points out in a long piece about Philip Larkin, "writers' private lives don't matter, only the work matters". And the work that matters here is – unarguably, indisputably – the literary criticism. Naturally, we have been here before, and in some cases we have been here repeatedly (Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike), but it takes only a glance at the Larkin stuff (an introduction to Selected Poems, a review of the poet's letters to his long-term girlfriend Monica Jones), to reveal the depths of Mart's engagement, his habit of throwing out apercus in half a line that would detain most critics for a paragraph – for example, the thought that Larkin's longer poems resemble Victorian narrative poems – and his eye for individual physicality. Larkin, his godfather, is remembered for his "grave, cumbrous yet mannerly figure", which perfectly hits off the watchful but somehow gargantuan presence of the photographs.

Or there is Mart on the Andrew Davies TV adaptation of Pride and Prejudice ("The BBC's new serial has been touted in the press as revealing the latent 'sensuality' of Jane Austen's world: naturally it reveals the blatant sensuality of our own.")

That leaves only the politics and the public affairs (Trump, Romney, the Clintons, Princess Di), Mart's absorption with whom, I frankly confess, leaves me baffled, or rather disappointed, given the glories of what went before, notably the pieces of United States political reportage collected in The Moronic Inferno (1986) and Visiting Mrs Nabokov (1993).

Is it that he knew less about America then, but wrote better, or merely that Ronald Reagan possessed some faint vestige of charm, depth or humour to which his modern equivalents can't aspire?

The Rub of Time ends with a couple of book reviews from 2015, contributed, respectively, to Vanity Fair and the New York Times Book Review, and once again about Vladimir and Saul – oddly sedative affairs ("It is the prose itself that provides the permanent affirmation. The unresting responsiveness; the exquisite evocations…") and neither of them a patch on anything in The Moronic Inferno.

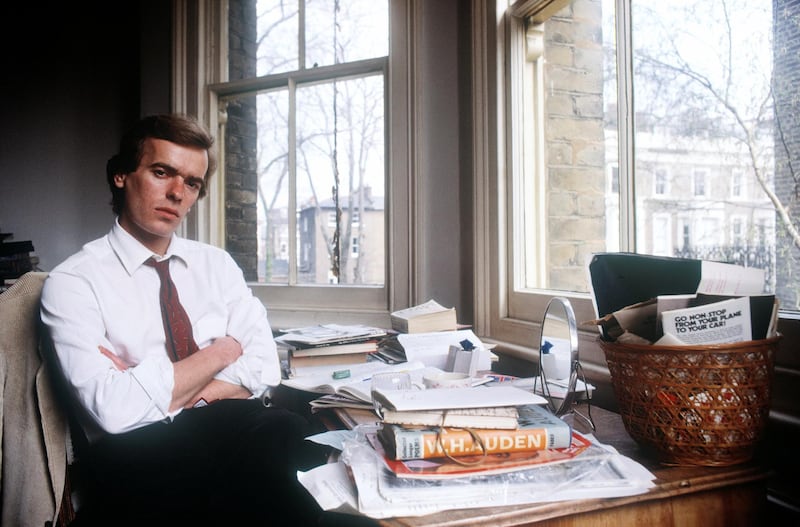

But this is not so much a case of the reviewer showing his age (68 and counting) as me showing mine, and remembering that long-dead world of 1980s Eng. Lit, through which young Mart – Jagger-like and disdainful – strode like a molten God.

_______________

Read more:

[ Suslov’s Daughter by Habib Abdulrab Sarori covers five decades of Yemeni history ]

[ Book review: Colin Grant crafts a thoughtful eulogy in A Smell of Burning: A Memoir of Epilepsy ]

[ New non fiction for September ]

_______________