Hollywood likes stories about eccentric recluses, whether they are holed up in their mansions, like Edie Beale's Grey Gardens or Charles Kane's Xanadu, or creating works of genius in obsessive isolation. Perhaps that's because there's something of the madman-genius in all great directors: for every outgoing Woody Allen or Quentin Tarantino there's a publicity-shy Stanley Kubrick or Terrence Malick, generating wild rumours about their introverted behaviour.

In the wake of Malick's Palme d'Or-winning The Tree of Life, much has been made of the director's long-term commitment to avoiding the usual publicity game of interviews and appearances. No red-carpet appearance at the Cannes International Film Festival last May, no photographs allowed, no comments on the film's success. When the Cannes screening ended, the usual cutaway shot of the director's reaction was replaced with one of Malick's empty chair.

Films: The National watches

Film reviews, festivals and all things cinema related

[ Film ]

The director's behaviour, too, seems to follow the script of the isolated perfectionist. Malick started writing the screenplay that would become The Tree of Life decades ago. He is meticulous in researching his period pieces; for his 2005 Pocahontas story The New World, he digitally added a now-extinct parakeet to footage of 17th-century settlers arriving in Virginia, taught actors a dead Native American language and planted historically accurate strains of corn and tobacco.

Malick is also notorious for editing and re-editing radically different versions of his films right up to their release - something that has alienated actors in the past. Adrien Brody complained publicly when much of his role was cut from Malick's Second World War drama The Thin Red Line; other actors, including Billy Bob Thornton, Martin Sheen, Gary Oldman and Mickey Rourke, had their parts cut completely.

It has been reported that The Tree of Life had a similarly fluid script and conception. Although some aspects of the film - the lighting, the period detail - were tightly controlled, the director encouraged actors to improvise, and deliberately threw cast and crew off their stride mid-take to encourage spontaneity. Child actors would be told to run, unplanned, into a scene, and cameramen would be shoved while filming to give them a different angle.

Malick's sometimes eccentric behaviour, added to his need for extreme privacy, encourages journalists to paint him as a classic, Citizen Kane-style recluse, but there are different reasons why directors and others end up shunning the limelight. Stars can go into hiding because they're plagued by inner demons, but sometimes they are forced to retreat by outside pressures, while some simply cannot be bothered to expend energy on anything other than their craft.

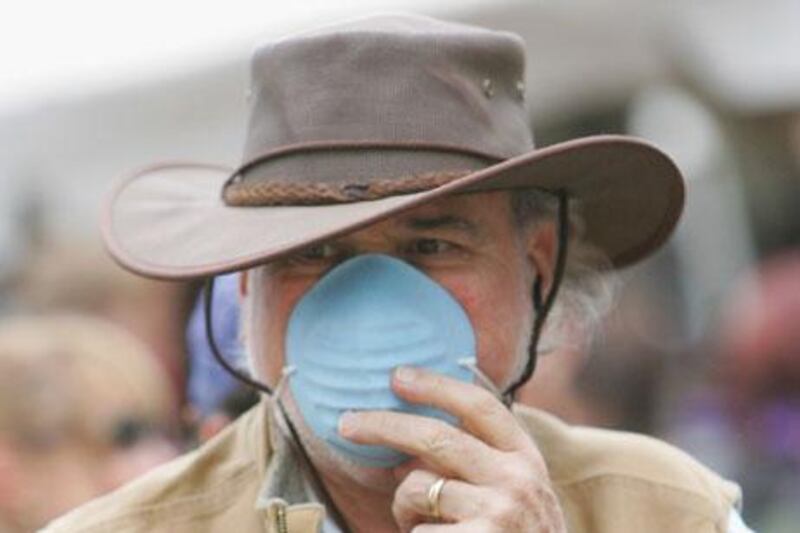

Howard Hughes and Stanley Kubrick were examples of the first sort of recluse. While stories abound of Hughes's mental health issues - his staff manual on how to open a can of peaches by scrubbing it first and not letting the can touch the bowl, the three months he spent in a studio screening room without leaving, his extreme fear of germs - Kubrick's eccentricities, which some have speculatively linked to Asperger's syndrome, are less extreme.

But both were, by all accounts, obsessive. Those close to Kubrick have talked of his secrecy, coldness and perfectionism as a director. He spurned publicity, worked and lived in a mansion in Hertfordshire in the UK, and refused to fly to other countries - which meant that films set elsewhere, such as Lolita and Full Metal Jacket, in fact were shot in Britain; for the latter, dozens of palm trees had to be shipped over to try to recreate war-torn Vietnam in the outskirts of London.

The Wachowski brothers and Ingmar Bergman fall into the second camp. Bergman had a breakdown after being arrested for tax fraud, and gave up filmmaking for almost a decade, while Larry Wachowski's personal life - dating a professional dominatrix, and supposedly being spotted in public dressed as a woman - must have been at least a contributing factor in the Matrix directors' commitment to keeping a low profile.

And finally, there are the likes of John Hughes, who abandoned directing at the top of his game in the early 1990s and moved back to Chicago to live quietly until his death in 2009. It is into this category of recluse that Malick fits best: people who are simply happiest away from the madness of the film industry's centre. He does not lack the sort of perfectionism that marked out Kubrick as special, but he is also reported to be a warm, friendly man, both on set and off.

The actor Brad Pitt, who plays the father in The Tree of Life, spent many of his promotional interviews for the film explaining Malick, who took a 20-year break from filmmaking between Days of Heaven (1978) and The Thin Red Line (1998). Speaking to The Guardian newspaper, Pitt pointed to the facts that the director - "an extremely internal man" - had been a Rhodes scholar in philosophy, and had translated the German philosopher Martin Heidegger.

"When he started making films in the 1970s," Pitt said, "you just made films. Today there are two parts to the job: you get to make something, but it's also become incumbent on us to suddenly sell our movies, and that's just not his nature. Terry's more the painter, or even the guy that's plastering the walls or laying the stone. He's just a very humble, sweet man."

Malick's always going to be seen as slightly eccentric by the Hollywood establishment, but avoiding playing the fame game could be the sanest move he has made.