Henry Hayden has it all: fame, money, a beautiful home and a loving wife. He’s a best-selling author; one of those rare breeds who manage to combine extraordinary sales figures with critical acclaim.

This perfect existence is built, however, on a fundamental falsehood. Hayden doesn’t write his own books. It’s his unassuming and attention-allergic wife Martha who’s the real genius.

Noms de plumes are, of course, nothing new in the world of letters, but Hayden guards his secret so closely that even his editor, Betty, and publisher, Claus, have no idea that the manuscripts on which the fame and reputation of the Moreany Publishing House rest aren’t the work of the man who’s always claimed to have written them.

Hayden’s first novel, a thriller titled Frank Ellis, sold 10 million copies worldwide. It was adapted for the stage and screen, and is now a set text in schools, having arrived in their slush pile at just the right time to save them from bankruptcy.

Hayden has successfully executed this deception for eight years since he first submitted the pages of Frank Ellis to Moreany after discovering them collecting dust beneath his then wife-to-be’s bed.

Despite his happy marriage, incidentally, he’s also been having an affair with Betty for the duration of their working relationship, a liaison that’s suddenly escalated in complication given that she’s recently become pregnant and is pushing him to come clean with Martha.

But if he admits to one lie, it’s more than possible that all the others will come crashing down around him too? Instead, he makes a rash decision to end it with Betty once and for all, but his plan backfires and somebody ends up dead.

“You can’t image how awful it is to have a secret,” Obradin, Henry’s Serbian friend, the local fishmonger, tells him.

The author has made his buddy promise not to reveal any knowledge of his existence to fans seeking a glimpse of the famous writer in his hometown.

But Henry, having harboured secrets his entire life, knows better than anyone what it feels like. His may be more deeply buried than most, but he’s not alone. Each of the main characters in The Truth and Other Lies are keeping something close to their chests: Betty’s hiding her pregnancy from her colleagues; Claus his terminal cancer diagnosis; Claus’s nosey assistant Honor keeps what she sees and hears to herself; and even Hayden’s stalker, a nemesis from his schooldays who’s out to expose Hayden’s fraud, has his own skeletons in the closet. But this only adds a series of extra dimensions to the already tightly coiled, perfectly paced plot.

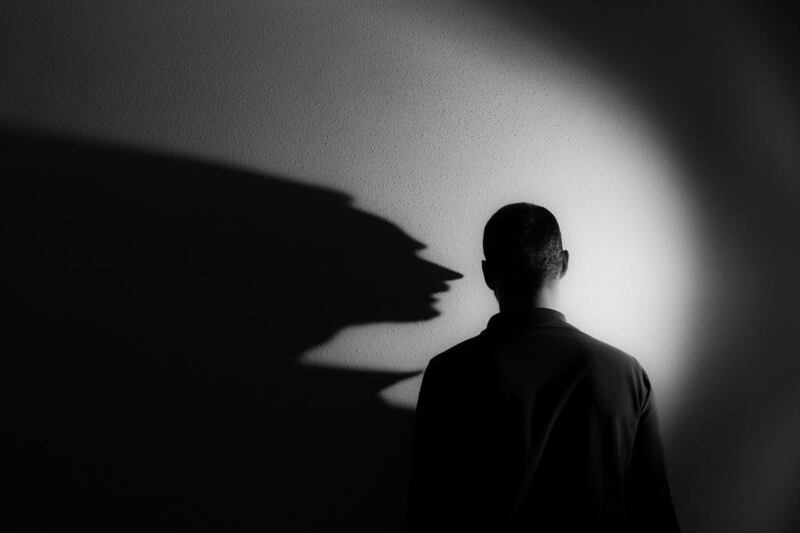

Hayden might well be incapable of writing the books he’s famous for, but this isn’t to say he’s not creative. Like Patricia Highsmith’s infamous Tom Ripley, he’s a product entirely of his own invention – his past is a “minefield” of unexploded bombs in the form of the countless untruths he’s told about himself along the way and the ellipses and omissions in his history. Nothing about him is real, but yet he’s a man who gives the impression of endless achievement, possibility and potential.

“Every sentence is a stronghold,” writes a critic of Hayden’s work, a phrase he admires.“It was so wonderfully pithy, Henry thought, it might have been something he would say. But it wasn’t. Nothing was his.”

The irony, of course, is that although he doesn’t write his own thrillers, he ends up orchestrating a real-life murder mystery and playing a subsequent cat and mouse game with the authorities on his tail; directing the people around him with the same whim and ease as an author positions his protagonists.

Arango is one of Germany’s most prominent screenwriters, and from the dexterity and speed with which he handles his plot here, one can see why.

Hayden is also a wonderfully multifaceted character, but Arango wields this complexity surprisingly gracefully, offering us a profile of amorality peppered with cruelty and kindness in equal measure – an intriguing, although often somewhat baffling mixture. The text is also beautifully translated by Imogen Taylor; Arango’s wry humour shines through: “Solving crimes is as difficult and laborious as committing them, with the difference that the lunchbreaks are paid.”

Lucy Scholes is a freelance journalist who lives in London.