From the moment it was unveiled - with an impromptu antismoking protest wrecking the opening ceremony - to its conclusion tomorrow, Antony Gormley's One & Other, often known as the Fourth Plinth Project, has been a focus for controversy and debate. For some, his invitation to 2,400 people to spend one hour alone on an empty stone plinth is a fantastic piece of art that has created a collective portrait of Britain among the stern, stone statues of London's Trafalgar Square - that traditional centre of protest and celebration in the UK. For others, it is a squalid symbol of creatively barren exhibitionism.

What is certain is that when the last plinther is lifted off their perch, there will be a vacuum. Because within 24 hours of its opening on July 6, this public art project had, as Gormley observed, become as much part of the British summer as Royal Ascot or the Henley Regatta. "I was expecting it to stand out like a sore thumb," he says. "But within hours of it starting, it was absorbed into the daily life of the city."

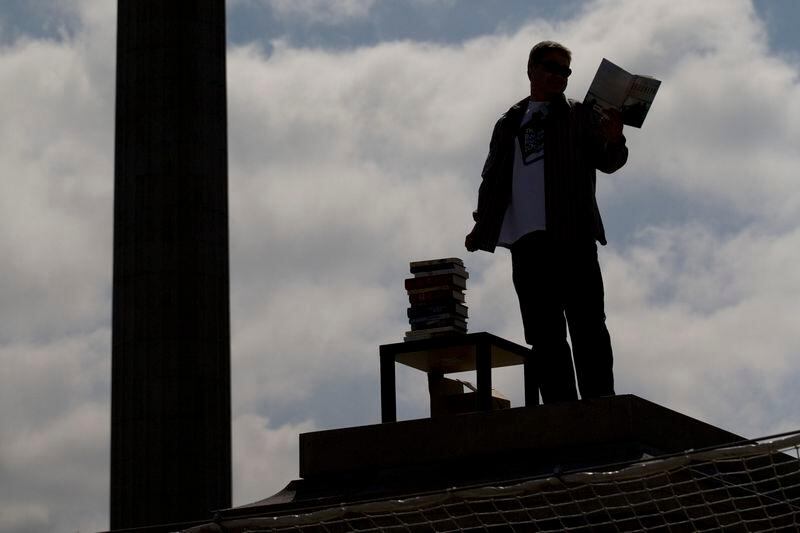

The project is now so much a part of life that only a small crowd - usually made of tourists, relatives and friends - gathers around each plinther who stands high above the square. An audience will gather if they see a man in a Godzilla costume demolishing a cardboard replica of the London skyline or a woman taking her clothes off, but quite often people can walk by without giving the living statue a second glance.

But the debate around the project has not gone away. Writing in the Guardian newspaper last week, the art critic Jonathan Jones wrote: "It is a portrait of a society in which people will try anything to get their voices heard, even stand on a plinth, but where no one can hear what they're saying." In July, Janet Daley in the Sunday Telegraph was more fierce: "For many who have been simply bemused or faintly exasperated by the defiant narcissistic vacuity of contemporary art, the Gormley project... is a step too far. It is a defiling of a civic space that belongs to the country... which should be treated with dignity and respect."

But these voices in public print, though the loudest, are not necessarily the ones that sum up people's reaction to the project. Sky Arts has presented a weekly programme on One & Other and streamed the plinth appearances live on the internet day and night. Figures show that there have been 7.3 million hits and nearly 700,000 people have logged on for an average of more than nine minutes, which indicates that the project has become something of a worldwide phenomenon.

John Cassy, the channel's director, says: "That shows you are getting a lot of people to sample public art. It's sparked a bit of debate and got people talking about it - and that has got to be good." Certainly over its lifetime, the plinth has displayed a huge variety of activity. The participants were chosen by a regionally weighted computer programme and so have come from all over the UK - and though the majority seem to have been in their 20s or 30s, all age groups have been represented.

Many people have used the plinth to convey a personal message, perhaps to say how much they love someone or to propose marriage. Others have become protesters, taking their hour as a means of raising concerns about everything from the war in Afghanistan to child cruelty to the state of bee-keeping. Unexpected numbers have sat drawing or knitting, making their own art. An enormous number have used their hour in the public eye to reveal all. "The British do love taking their clothes off," says Cassy. This has prompted shocked passers-by to occasionally call the police, but being naked is not an offence under British law.

There has also been a lot of dressing up and a lot of dancing; one of the most memorable plinthers managed to engage a good proportion of the audience in a spot of line dancing. Other people just wave and wiggle around in a rather pointless manner, some dance or move with a fair degree of professionalism. On three of the occasions I have visited Trafalgar Square to see what was going on, I have been faced by men with bikes. One lost his bicycle in the down blast from a helicopter that arrived in the square to tend to a nearby emergency, and spent a considerable time on his stomach trying to retrieve it from the netting that surrounds the plinth. The helicopter was rather more exciting.

But to expect entertainment from the plinthers, is, Gormley says, to miss the point of the exercise: "People have assumed the piece is about performance but it absolutely is not. The burden is on the viewer, not on the person on the plinth, to investigate this representation and discover what it means. "There was an assumption that being a spectacle was enough, but it wasn't. The people on the ground looking up are the other half of the picture. Those plinthers who were able to deal with that and weren't unsettled by it brought some of the best results to the project."

Sandy Nairne, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, which is around the corner from Trafalgar Square, has experienced that burden of expectation first-hand. He initially chaired the committee that shortlisted Gormley as an artist to fill the vacant fourth plinth with his work. His gallery has streamed the results into its entrance hall, and its Youth Forum has been heavily involved in blogging and tweeting about the piece.

Nairne also placed himself on a reserve list of residents who would step in if a designated plinther failed to turn up. So it was, with 10 minutes notice, that he found himself sitting on the plinth with only a sketch pad for company. "It was quite fascinating," he says. "It's pretty high and you do feel a long way up. And the way you are taken to the plinth in a mechanised cherry picker does make you feel that you are in a contemporary version of a tumbril.

"I don't think I was exactly nervous but the adrenalin was certainly running around by the time I came down, particularly. You do feel under pressure because you've got the time and you're very exposed. I took my sketch book and focused on that because I will never see that view again and it was what I wanted to do, but it was pretty boring for people watching. There was a certain amount of heckling and someone called out: 'Entertain us!'"

Nairne says that when Gormley proposed the project, he was struck by its "brilliant simplicity". "As I remember it, it was a single sheet of paper with 'one person, one hour, one year' written on it." The year was rejected as impractical; even 100 days has represented a logistical undertaking, requiring the creative company Artichoke - which takes each participant through the health and safety requirements of their time on the plinth and ferrys them there and back as each hour ends - to man an unsightly temporary office in the square 24 hours a day.

In every other respect, however, Nairne says the project has fulfilled expectations. But he doesn't agree with Gormley's view that it represents a portrait of Britain. "It's a portrait of people who want to go on the plinth." Gormley says: "What it has been is a very formidable impression of lots of thoroughly good things about being English, like tolerance of a wide range of behaviour and an agreement to do things that might be thought of as being very silly just for the sake of it. I think there have been extraordinary moments of peace as well as of mayhem and I feel very lucky to have got away with it."

One man appeared on the plinth at 4am, dressed in jacket and wing collar, dancing on his own with no one watching. "It was very moving," Gormley says. A striking quality of One & Other is the way it has allowed people such as this man - ordinary people who are not normally celebrated by statues or websites or loud debate in papers - their moment of glory. For Gormley, this is a fulfilment of its aims.

"The basic proposal is: can we use the frame of art not as a zone of idealisation or of hyperbole but simply, by occupying that frame, look at ourselves? The piece has achieved that aim absolutely. "And it is often at the point of failure, of cessation of performance, that the thing becomes most telling - at the moment the plinthers run out of things to do and have to have a breather or the moment when you get the town crier sitting at the edge of the plinth looking at his e-mails. Those moments are precious."

The project has drawn attention to people in two different ways. For those in the square, the individual is dwarfed by the size of the buildings and statues around them; viewed on the web, the plinther comes into sharp focus, brought into close-up by the television cameras and lights. "It's ironic that the most intimate connection with the plinthers is by the most distant media," Gormley says. "The lights and mics that were linked with the net upped the ante about it being a frame. It became a test site where the tension between it being a playpen on the one hand and a kind of concentration camp on the other was quite severe. It was a place of meditation and of interrogation."

In the end, the reaction to One & Other depends very much on the viewer's response to that interrogation. It is possible to see it as an abnegation of creativity, as an opportunity for exhibitionists to show themselves in a poor light. But it is also possible to watch those frail individuals standing below the vastness of Nelson's Column and the National Gallery's soaring portico and admire the spirit that sustains them in their hour-long vigil.

Whatever their opinion, many people have been struck by the project's great good nature, its spirit of benign enjoyment. Detractors say that is all part of its feebleness. But for those who value tolerance, eccentricity and an ability to enjoy oneself in the face of overwhelming odds, there is something curiously inspiring about One & Other. For 100 days, it has helped to make Trafalgar Square a place of life and debate. It has stimulated arguments, opened minds and given 2,400 people an unlikely forum for self expression. It will probably be missed it when it has gone.