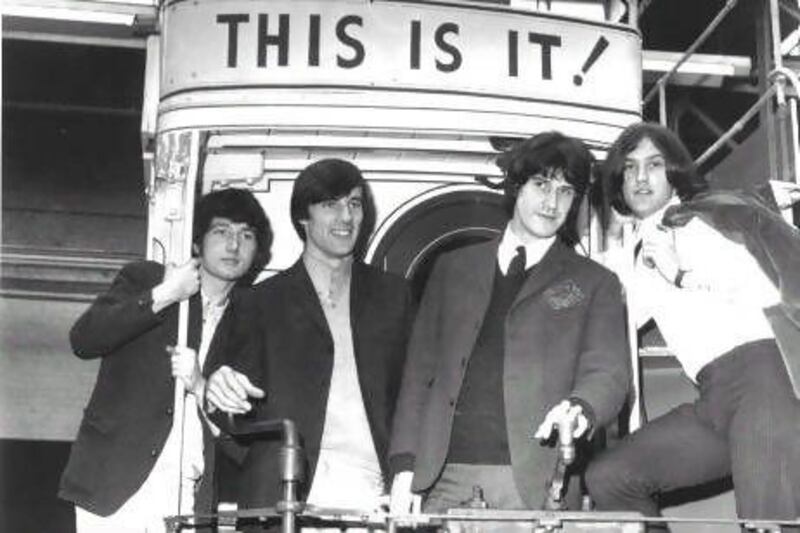

Before the London 2012 Olympic Games began, there was another Team GB flexing its muscles. This was not a competing team, but a formation selected by Danny Boyle, the director of the opening ceremony, and its remit was to illustrate on the soundtrack of that event the canonical nature of British music. Among its number were The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and The Who. And, even if not quite in medal position, it also included The Kinks.

To anyone who knows the group's work from its classic singles - from early compositions such as All Day and All of the Night to more wistful and romantic later work like Waterloo Sunset - this won't have been much of a surprise. But for those who have followed the group into more obscure work like The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society it came as an endorsement that the group (whose chief songwriter, Ray Davies, spurned prevailing trends and enjoyed mixed commercial fortunes) were nonetheless being recognised and celebrated as part of the most historic British music.

The Kinks, after all, might be seen as problematic. They were not the most spectacular, the longest-enduring or the biggest sellers of their generation, and so the question of how best to serve their legacy is a complex one, asking as it does immersion in an often arcane world. Over the past year, many of the band's albums have been reissued in deluxe versions, charting Davies's passage from leader of a sparky beat group to accomplished thematic composer. There has been a mono box set - a move that appeased Kinks audiophiles, but also that tacitly claimed parity with The Beatles, who also released a set of their mono albums.

Of late, Davies has also seemed concerned with legacy. In 2007 he released an album of new material, Working Man's Café, but he has also essayed Kinks songs with a gospel choir The Kinks Choral Collection in 2009, and made an album of performances of Kinks songs with famous fans including Bruce Springsteen, Metallica and Mumford and Sons, See My Friends, in 2010.

You could see these as naked efforts to find a new market for these great songs. More likely, these decisions are the work of a slightly odd, highly self-critical person who is still searching for a way to do best justice to his material. This, after all, is someone objective to the point of writing his autobiography in the third person.

This month, these faintly contradictory Kinks/Davies qualities (a body of work with several obvious highlights, yet with no single obvious entry point) are being appeased by two separate Kinks releases. A hits compilation Waterloo Sunset - The Very Best of The Kinks & Ray Davies looks to snare any Olympic-maddened soul who might be interested in hearing more from the group on the strength of the number of songs Davies has written about London (the second disc compiles 22 of them).

The second is a box set called The Kinks at the BBC that brings us five CDs and a DVD of the band's recordings at the corporation, spread over 30 years, from 1964 (live turns for the Light Programme's Saturday Club) to 1994 (a session for DJ Emma Freud). There are gaps (specifically, the 1980s, during which time the band focused their attentions on the US). But throughout the journey, one gains an idea not just of the path that The Kinks took creatively, but also - valuably - a credible notion of how that eccentric course was received at the time.

The first couple of discs find the group following a credo not unfamiliar to many of the greats of British rock music of this period: a commitment to recreating the raw sounds of imported records by black American artists. As these CDs relate, the band are not so much interviewed at this time as they are prodded slightly unsympathetically by Light Programme presenter Brian Matthew, their long hair as much a point of conversation as their music. And in fairness, if you were to judge the band on the strength of their cover versions alone (brittle takes on I'm A Lover Not A Fighter and Little Queenie), maybe their oft-mentioned shagginess would have been the most interesting thing about them.

What the first discs go on to recount, however, is an explosion of creativity. Alongside these covers, the band quickly created their own idiom, their eureka moment being the proto-hard rock of You Really Got Me ("A love song without saying 'love' and 'dove'," as Davies succinctly explains it here). They then quickly outgrew it. As little as three years later, Davies has mastered slyly vitriolic character songs such as David Watts, whose narrators subtly twist the knife on their subjects. With the marvellous Sunny Afternoon, Davies effectively invents the urban pastoral form. Here, the once-wealthy protagonist is forced to fall back on the simple pleasures after a swingeing visitation from the tax man. As even the most coiffure-minded presenter could discern, these were very different kinds of songs.

Throughout these discs, the band's evolving career and the changing music marketplace is subtly evoked. Not long into disc two, around 1968, Davies is confessing that he and the band no longer have much time to stop by at a radio station for awkward chats about their hairstyles - they're too busy working. Diversification is very much the mode from this point forward: Davies is writing songs for other artists, themes for films, and operas for television. His talent is even being supported by commissions from within the BBC itself: a couple of songs destined for Ned Sherrin's satirical programme Where Was Spring? are here. Ray's brother Dave is writing some successful songs himself. Interviewers begin to question why the band have stepped off the treadmill of releasing new singles every few months and ask if the group's lifespan is coming to an end.

It isn't at all - but both The Kinks and the BBC are changing. No longer a band for sharp-dressed young ravers, as disc two closes and the third begins, The Kinks have found a new audience among the cross-legged listeners to John Peel's late night shows, and are throwing open the doors of their music to new influences. In person, Ray Davies still sounds like a slightly vague north Londoner. In his music, he has by now adopted some of the musical idioms of the American South, and on ill-advised occasions (Ape Man; Supersonic Rocket Ship) an approximation of the accent of Jamaica.

Still, many fans remained on side with him throughout the band's divisive "theatrical phase", as a fantastic In Concert show from the Hippodrome in Golders Green in 1974 (disc three) makes clear. The set list is weighted towards satirical recent songs about urban redevelopment (Demolition; Money) but is just as significantly awash with Hammond organ, tuba and great bonhomie.

Come the 1977 Kinks Christmas concert (disc four), Davies' musical/theatrical revolution seems to have reached its logical conclusion, and the band has returned to more orthodox rock 'n' roll, seamlessly incorporating a selection of faithfully arranged hits from their 1960s catalogue in among new material. Having voyaged to new places with their recent material ("This is another phase The Kinks went through ..." Davies says self-deprecatingly at one point), The Kinks of 1977 seem quite happy to return home to their older songs, like a commuter contentedly returning to his suburban semi. They have, in effect, become their own preservation society.

"Preservation" is a key word for The Kinks - and for this box set, too. A particularly characteristic section of it, in this regard, is probably disc five. It contains material that was wiped by the BBC (it was BBC policy at the time, nothing personal) but which has been recovered from fan recordings. It's a lovely indication of the affection with which the band are regarded, and a very Kinks attitude. No one is saying that these are the first things you'd save in a fire, but they are definitely worthy of being looked after by somebody.

It's a quality that runs through this box set. It can't perform a miracle and create for the band the definitive, Sgt Pepper's-style statement The Kinks never themselves made. What it does, though, is keep abreast of the band as they go about their business, keeping a faithful record of moments that might otherwise be ignored, but which gathered together add up to something very significant indeed: preserving the old ways, as the band once put it themselves, from being abused.

John Robinson is associate editor of Uncut and the Guardian Guide's rock critic. He lives in London.