'A spectre is haunting Eastern Europe: the spectre of what in the West is called 'dissent' … It was born at a time when this system, for a thousand reasons, can no longer base itself on the unadulterated, brutal and arbitrary application of power, eliminating all expressions of nonconformity. What is more, the system has become so ossified politically that there is practically no way for such nonconformity to be implemented within its official structures."

When the Czech playwright and statesman Vaclav Havel - whose state funeral was held in Prague yesterday - wrote these words in 1978, Czechoslovakia was under the domination of the Soviet Union. Obedience and conformity were strictly enforced and any semblance of dissent rapidly shut down. The state officially responded to any defiance of party control with severe persecution.

Havel was trying to make sense of what appeared, to him, senseless: the role of the individual in maintaining a system that was so oppressive. Yet his words could just as equally have applied to the Arab republics over the past few years.

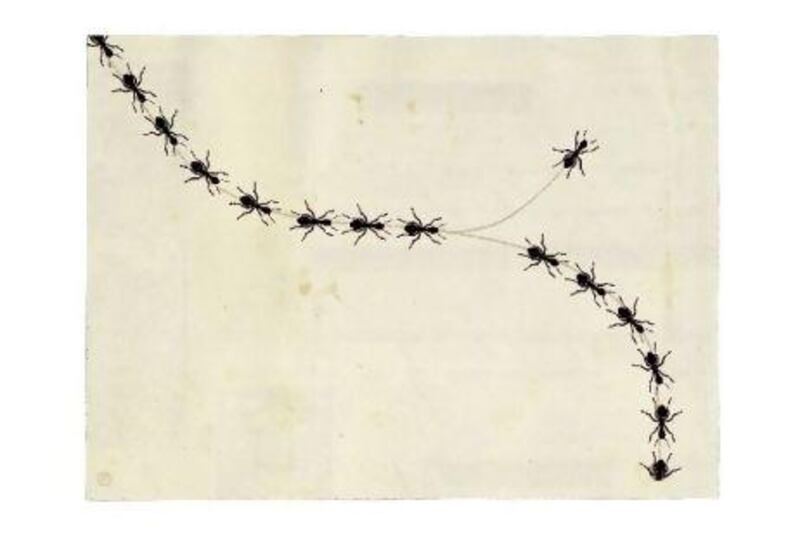

In his essay, The Power of the Powerless, from which those words above were taken, Havel wrote about a greengrocer putting the slogan "Workers of the World Unite!" in his window.

"Why does he do it?" asked Havel. "What is he trying to communicate to the world? Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world? Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals?"

The point, Havel wrote, was that the greengrocer knew the slogan was meaningless and didn't believe it. Moreover, no one reading the sign would believe it themselves, nor assume that the greengrocer believed it. It was meaningless, devoid of the content it purported to display.

Yet displaying such a sign profoundly mattered. It mattered, argued Havel, because it provided a panorama of power, a way of doing what everyone else was expected to do, in order not to stand out.

"The greengrocer had to put the slogan in his window, therefore, not in the hope that someone might read it or be persuaded by it, but to contribute, along with thousands of other slogans, to the panorama that everyone is very much aware of."

It was part of what must be done to live in society, the path of least resistance. Yet by following that path, the greengrocer was contributing, along with everyone else who displayed similar signs, to a totalitarian society.

Havel was writing at a time when dissent was dangerous in Eastern Europe, a phase of history that has passed from much of the region, although it is tragically reappearing in Russia. Yet the logic of the panorama of power remains alive, as can be seen in today's North Korea.

Here, following the death of Kim Jong-il, mouthing declarations of allegiance to North Korea's new leader is vital, even if they are hollow. The images of the Dear Leader and his father, the mythical stories of their past and their deeds, all of these are part of a panorama that citizens must participate in.

The cult of personality and the stability of the regime depend on these symbols. To challenge them in even the smallest way is to challenge the entire edifice of power.

(It is harder to judge, with such limited information coming out of the hermit state, whether the individual mourning is a genuine outpouring of grief, a reaction to a long-standing personality cult, or part of a panorama of power that requires such mourning, because not to be sufficiently sad is to suggest disloyalty.)

The panorama of power also thrived in many Arab republics for a very long time. In particular, it existed in countries that attempted to enforce a cult of personality, such as Iraq under Saddam Hussein or Syria under Hafez Al Assad. Yet even in those republics without a cult of personality, there was a cult of believing in the state, in mouthing platitudes about the president as the head of the country, a leader whose rule was legitimate. Egypt, Yemen and Tunisia would fall into these categories.

Offices and shops all across Iraq, Yemen and Syria displayed photographs of the president, not because they especially wanted to, but because the alternative was to invite questions and suspicions. Nobody said anything if you displayed a photograph of Hafez Al Assad. The questions only started if you didn't.

What is the danger of challenging this panorama of power? What is the danger to the greengrocer of merely not displaying the sign? What if the greengrocer simply takes it down?

Havel writes: "The greengrocer has not committed a simple, individual offence, isolated in its own uniqueness, but something incomparably more serious. By breaking the rules of the game, he has disrupted the game as such. He has exposed it as a mere game. He has shattered the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the system. He has upset the power structure by tearing apart what holds it together. He has demonstrated that living a lie is living a lie."

As much as displaying the sign was meaningless, not displaying it was not meaningless. Quite the contrary, it was infused with meaning. It was a severe challenge to the system and as such invited severe retribution, because these symbols of obedience mattered - it was important that everyone see these symbols, though none believed in them, a panorama of obedience.

That is precisely why, during the Arab Spring, small actions against the regimes brought enormous retribution. The Syrian uprising began because a group of children scrawled a revolutionary slogan on one wall in a small town far from Damascus. But they were arrested for it, because to commit even that smallest of transgressions was to show how lacking in clothes the emperor really was. And once people accept that the emperor has no clothes, it is impossible, to mix metaphors, to put the genie back in the bottle.

In Egypt, the regime collapsed because of a surprisingly small action: when a curfew was declared and protesters were warned to leave Tahrir Square, they simply didn't. The entire edifice of fear was based on the idea that the people would retreat in the face of violence. But they didn't. No one left and more streamed across the bridges to Tahrir. Faced with a such a small gesture, the whole edifice of fear collapsed, and Hosni Mubarak left.

Vaclev Havel and the world he was writing about have largely passed into history. But the panorama of power has not. The ability of individuals to hold up a system that weighs heavily on all of them is astonishing, and they do so to avoid being crushed under the weight of it.

There are still places where this panorama of power exists, countries such as North Korea, Algeria, Belarus or the Central Asian republics.

Havel may now be a historical figure, but his words remain a living reality for too many.

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist at The National.

From Prague to Damascus, the same lies and the same fears

The path of least resistance leads to a totalitarian society.

Editor's picks

More from The National