In October 2013, to coincide with World Space Week, Warner Brothers released Gravity. It grossed US$723 million (Dh2.65 billion) worldwide at the box office, and for good reason: Alfonso Cuaron's operatic masterpiece set in space brought back a sense of awe to the art of cinema. In many ways, it also redefined the concept of sci-fi in filmmaking, with some critics heralding it as a "contemporary space thriller", instead.

Gravity struck a chord with the average cinema-goer for two reasons: on one level, it helped us understand the perils that astronauts take on so bravely as part of their profession. For all the scientific advancements we've made through the decades – and for all the entrepreneurial bravado of the likes of Elon Musk and Richard Branson – space exploration is still fraught with danger. And Gravity used this aspect of the vocation rather effectively to create a nail-biting thriller that worked at its own languid pace. And in casting Sandra Bullock as a "woman in distress" in the celestial beyond, battling with her inner demons (the accidental death of her daughter is an underlying motif in the movie), Gravity becomes more than just a sci-fi spectacle. It becomes part of an inner monologue: an existential trope that makes for groundbreaking cinema, with the screen symbolising an oracle asking the audience: "How far can you run to hide from the truth?"

The milieu of outer space and space travel, while providing Hollywood a canvas to make huge technological leaps in special effects, has given its writers and directors a context to explore the human condition. For instance, in Robert Zemeckis's Contact (1997), Dr Ellie Arroway (played by Jodie Foster in one of her most underrated performances) is a SETI, or Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, expert seeking "contact" with life beyond Earth.

She is successful in her diligent efforts, only to meet an alien that impersonates her deceased father. An equally telling moment in the film is when Dr Arroway's candidature to "represent" our planet to aliens is scuppered by a committee member who brings to light her atheism: based on this, she is deemed unfit to be an ambassador for Earth to aliens. Contact, like Gravity, again brings to high relief the anxieties and beliefs that nail us to this planet. It creates for great fictional tension in both the films.

Similarly, Denis Villeneuve's Blade Runner 2049 (2017), set in a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles, features a tribe called "replicants", or bio-engineered humans. Again, like Gravity and Contact, it shows us that while science has the capacity to marvel us mortals with its ability to instil fake memories in cyborgs, it is ironically, in fact, the state of being human that has the highest currency in such a dystopia. Ryan Gosling, who plays a "replicant" named K, faces his biggest existential crisis and breaks down on realising that he is, after all, not human. Science fiction, for all its lofty imagination and tech wizardry, is all about mankind's collective zeitgeist, which more often than not, has been dark.

Aside from the existential crises highlighted in some of the "spaced-out" films above, political disillusionment and environmental catastrophes are constant metaphors in science fiction. For all the aeronautical advancements of the Apollo era (1960 to 1972) that allowed science fiction to become "reality" on screen, the bleaker truths of Planet Earth have always been leitmotifs in films set in outer space. In Sunshine (2007), directed by Danny Boyle, for instance, it is 2057, the sun is dying and a mission is sent to re-ignite the star. The fragile disaster-prone environment of a spaceship thus becomes a metaphor for our disregard for Planet Earth – and the consequences that have befallen us as a result.

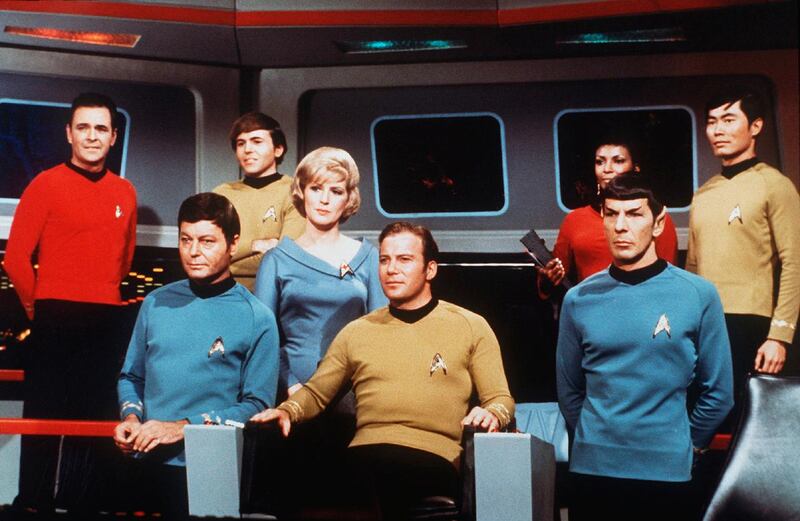

Some of the most successful science fiction franchises are undoubtedly Star Trek (which debuted in 1966) and the Star Wars series (1977) – they blended our fascination with outer space with their own patented mythologies to create a universe unto itself. It made for great popcorn entertainment, but one could never quite find a deeper meaning beyond the spectacle and the plethora of merchandise these franchises inspired. However, in the 1970s, often considered the heyday of the genre, rising above these blockbusters, came a science fiction classic that has fascinated cinephiles for decades: Ridley Scott's Alien (1979).

When Alien hit cinemas, the slasher movie as a genre had begun to come into its own – creating concerns about the depiction of women in films. It was barely a year since Jamie Lee Curtis had become the world's most successful "last girl standing" with John Carpenter's utterly brilliant Halloween (1978). Merging the genres of horror and science fiction, Ridley Scott crafted one of the decade's most cherished gems. In fact, to many film critics, Alien is a feminist sci-fi horror film. "It was pitched as "Jaws in space", but director Ridley Scott's Alien couldn't have been more different to Steven Spielberg's blockbuster. Unlike Jaws (1975), Alien didn't indulge in attacks on female skinny-dippers. Instead, it channelled a second-wave feminism to reflect and critique the slasher genre's spectacle of violence against women," said Sadek Kessous in The Independent. Set in a spaceship contaminated by a monster, all the men in Alien die violent deaths, leaving leading lady Sigourney Weaver as the … last girl standing." It's a great subversion of the form.

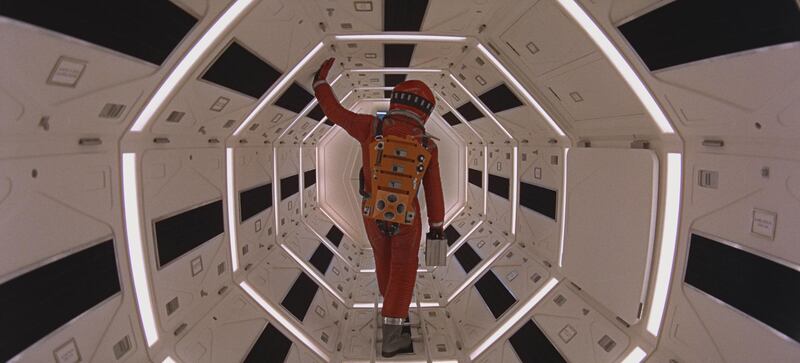

Almost all science fiction films owe their craft to two works of art: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Frankenstein is the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a monster in his laboratory to horrific results. In creating a doomed scientist working with advanced technology, Shelley, 200 years ago, forewarned humankind of the dangers of technocratic hubris: this is not very different to some of the warnings that contemporary science fiction wishes to draw to our attention.

Similarly, 50 years ago, 2001: A Space Odyssey inspired film technicians for generations to come. From Ridley Scott to Steven Spielberg to George Lucas, many directors have also acknowledged the film's legacy in having created a market for the "science fiction blockbuster".

______________________

Read more:

Film Review: Sriram Raghavan's 'AndhaDhun' is a must-see

Chris Evans hangs up Cap's shield after wrapping 'Avengers 4'

Is Salman Khan's 'Bharat' set to be an absurdist masterpiece?

______________________