In the three days that followed the Beirut explosion, my screen-time consumption was averaging eight hours a day. Transfixed by the uncanny imagery of a mushroom explosion defacing the city of my birth, I eventually descended into a physical lethargy and an inability to speak. My condition would only start to ease after I booked a flight back home and confirmed a crew for a week of story-hunting amid the carnage.

I last lived in Beirut 22 years ago when I was a film student. The city continued to inform the filmmaker I am for years to come as I made films in Montreal, Dubai and Berlin.

Its gardenia-lined alleys and majestic coastline grace my first films. Many years later, I would make Grandma, a Thousand Times in the city and capture a rich familial culture that charmed audiences. I needed to reconcile the city I carry within me with what remains of it. Capturing that on film was to be a way of coping – perhaps the camera can diffuse a shock that can blind the eyes and crush a heart.

A week after the explosion, Beirut glistens and gleams in its glass debris. Crushed glass covers the streets like Christmas snow. Shards swept into piles by residents flicker in the midday sun. In cracked mirrors and window panes, one can see scarred reflections of familiar streets. Many of the scars sustained by Beirut victims are from glass as well. The many who were seduced to their windows at the moment of the explosion absorbed its shards in their faces and bodies.

My cousin's daughter, Leya Jalloul, is one of them. A beaming 24-year-old, she sustained 100 stitches from a collapsing glass door at her local gym. Luckily, her eyes were spared. "Day after another, I appreciate these scars," she tells my camera confidently. "They are part of something I have lived."

Her words ring true for thousands with this defining injury. At Rizk Hospital, Dr Mawad confirmed that plenty of the city's glass had to be extracted from its people's flesh.

Beirut always bared its scars proudly. Its buildings are known for bullet holes and shelled walls where birds build nests. To each building, there is a singular look and a war story. But the port explosion damaged the city differently. Filming the neighbourhoods of Mar Mikhael and Gemmayzeh from the road facing the port, it seems as if the damage was caused by a biblical tempest. Buildings are thoroughly hollowed out by the pressure, sometimes with the back walls bursting open. Corrugated iron is bent in the same direction. One can picture the massive blow and its direction. I obsess, imagining the sound of all urban structures being deformed at once, before the glass fell down in a long shower.

The explosion dealt a final blow to Beirut's vanishing heritage. For a few years, the city's oldest houses have been falling one by one at the hands of relentless developers vying for prime locations for modern property projects. Many of the remaining houses were too old to withstand the explosion. As their owners struggle to repair and maintain, the developers are now trying to seal quick deals. Disaster capitalism is thriving amid the carnage. My interview with Nicole, a survivor's wife, was interrupted by three different calls from bidders on her destroyed car. "How do they find your number?" I asked. "They probably collect plate numbers and share them with insiders at the registry who pull phone numbers up for them," she said. Even private data is on sale for a price.

Regardless of the experience of the explosion, some stories were repeated by many. Everyone thought that the blast took place right on their street. All assumed they were the only ones injured, until they got to the street and saw others were as well. Many described to me an empty gaze that people had following the explosion, as they walked around aimlessly in their wounds. That empty gaze lingers still in many. In Beirut, voices are shrill.

A rage pervades when people speak of the crime perpetrated against them by their own government and the abandonment that followed, as they were left to salvage their lives on their own. The clean-up on the streets and the hot meals being delivered to some homes are all out of volunteer civilian efforts. No one I spoke to was offered compensation by the government or promised help to patch up their homes. Few want justice; many want revenge.

Nonetheless, the Beirutis seem to be hard at work, building and fixing, even without access to income or savings. As they help each other in a stellar display of civic duty, they vanquish the myth of sectarianism which kept politicians in power since the mid-1990s.

In the low-income neighbourhood of Karantina, the poor and the refugees languish out of sight. Even TV crews don't go there. Many of its residents live on rooftops behind corrugated iron on poorly built buildings. So their loss of life was high when the port exploded 400 metres away. The Syrians of Karantina are too aware of autumn coming soon. Rain is potentially life-threatening without a roof above one's head.

Around me and the people I interviewed, the coronavirus was still spreading like wildfire. At the time of my shoot, Lebanon was recording 600 cases a day. For days, I talked to people while muzzled by a C-95 mask, my hands covered in disposable latex gloves. People answered from afar, while a zoom lens compensated for the necessary social distancing. My diligent line producer ran back and forth between me and them to offer hand disinfectants. The pandemic challenges the empathetic core of documentary-making. I could not shake the hand of a single person I interviewed.

At night, Beirut is a city of ghosts. I took nightly strolls between Hamra and Ein Mreisseh, walking the paths that impressed upon me as a younger man. The smell of gardenia and the salt air near the Corniche are palpable still. But many shops are out of business. Some of my favourite childhood restaurants have shut down forever, as they were caught in the downward spiral of poverty and low demand. The few that remain offer limited menus and close early. My hotel in Hamra does not offer milk with coffee. "Demand is so low, we had to cut down on items," the manager tells me.

My feisty grandmother survived and wants to embrace life like many of my people. I visited her briefly, and painfully decided that she would be safer if we did not hug. We sat at a distance and spoke of family and people’s pains. The explosion flung her shisha pipe in the air and brought down a window pane. “It was like an earthquake,” she said. “Worse than anything they have done to us before. May they be damned.”

At 95 years old, she is almost the age of Lebanon. She can testify to what misery this country has seen.

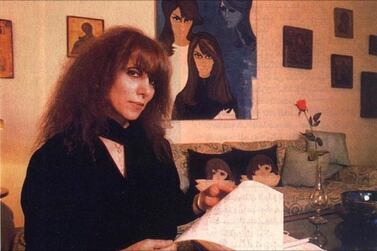

Mahmoud Kaabour is a Lebanese filmmaker who lives in Berlin. He is currently documenting the aftermath of the Beirut explosion