The unpaved desert road to Gabal Elba mountain is marked by small sand hills that stretch for miles and miles.

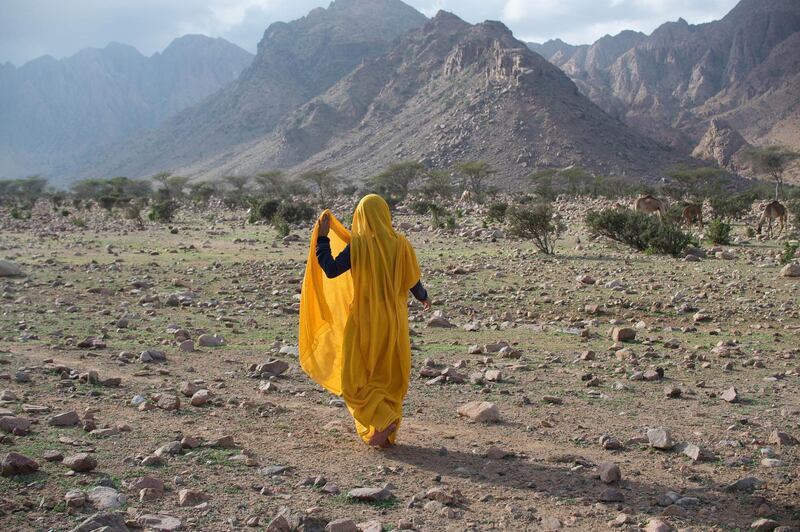

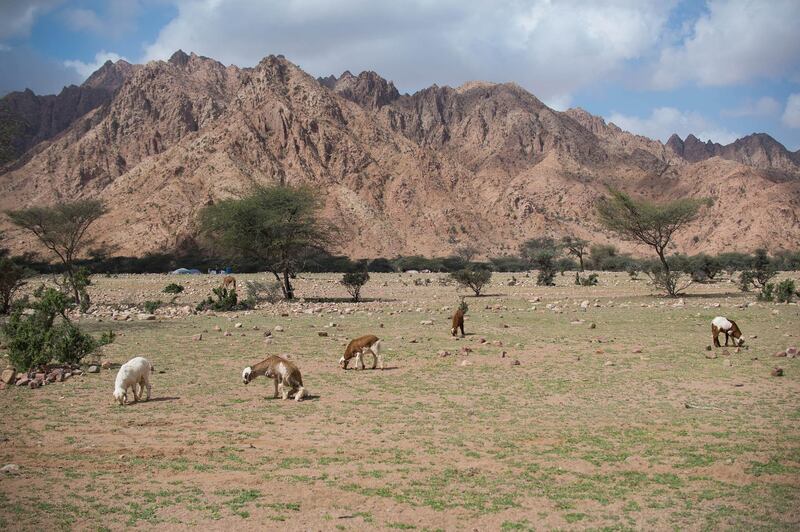

Subtle signs of life — scattered wooden huts and water tanks — gradually appear as the road goes deeper into the protectorate. The desert becomes greener, hinting at the mountain's closeness. There are more huts and more people. Wide spaces are left between each hut, so as to give each family a degree of privacy. A few men from the semi-nomadic Bishara tribe can be seen walking through the valleys with grazing herds of goats wandering around them.

The richness of biodiversity in the protectorate, located in Egypt's south-eastern corner by the Sudanese border, is unparalleled throughout the country. The mountain and the 36,000 square kilometres which surround it were declared a Protected Area (PA) in 1986 and are home to a great variety of animal and plant life. However, many of the region's species are now thought to be endangered.

"Gabal Elba is considered a semi-tropical habitat, and it is very special for Egyptians because it contains this sort of African biodiversity that we don't see in our predominantly desert habitats," says Noor Noor, an environmentalist.

The tribal life

There are two indigenous tribes that live by Gabal Elba in the winter and spring seasons — the Bishara and the Ababda. Members of the Rashayda tribe can also be found in the region, but to a lesser degree and they are not considered indigenous to the protected area.

Ali Dorah, a member of the Bishara tribe, and a professional birdwatcher who lives between Halayeb and the mountain, says that "customs determine where [tribes] gather and stay in the valleys". He says that the different tribes usually stay close to wherever the rain falls.

According to the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency studies, the tribal women build "portable matting houses" for their families to live in until they migrate elsewhere, especially when the scorching summer sun starts to beat down.

"The people of the mountain are considered independent and they rely on the water springs of Elba," says Dorah. "The population around the mountain increases along with the winter rain and the growth of goats and sheep."

________________

Read more

Hike the ancient Bedouin lands on the Sinai trail

Living in the shadows: Yazidi women tell of ISIS hell

Inside the dhows of Abu Dhabi's Mina Zayed

Fadi Kattan: The Palestinian chef dishing gourmet cuisine under occupation

________________

For the rest of the year, the tribe moves between Egypt and Sudan.

The Bishara tribe mostly speak an unwritten language called Beja, and some of them speak Arabic as well. The tribe has a rich and largely undocumented oral tradition. For example, Dorah recited one myth about a dog that used to help a manhunt goats. One day, when the pair caught a goat, the man took the meat, did not allow the dog to eat it and threw him the bones instead. The dog was upset and ran away, so the man and his wife walked around to look for him, calling out the dog's name, "Kotob … Kotob." Eventually the man and the woman became lost and were separated from one another.

"To this day, when the people hear birds calling out, they say that it is the sound of the man and the woman calling out for one another and their dog," Dorah said.

According to Dorah there are 60 to 80 large [extended] families living in the protected area.

The Ministry of Environment says there are no statistics about the number of the entire region's population, but unofficial estimates suggest there are 20,000 people living here.

The impact of climate change

These communities depend on their livestock as well as charcoal production for their livelihoods. The men also work in the camel trade, and sell other goods such as sesame and honey, Dorah says.

During the winter and spring, the clusters of mountains and their peaks turn a bright green, a sight which is difficult to find anywhere else in Egypt. Unfortunately, over the past years, the amount of vegetation on the mountain has decreased.

"Climate change has led to a decreasing amount of rain," Dorah says. Due to drought "the natural resources, both in terms of plants and animals, which used to support the stability [of life] in the valleys have deteriorated".

“The plants and the animals depended on the water,” says Dorah.

"Many plants are now incapable of surviving in their original locations, and fewer plants mean less plant-eating animals and eventually fewer carnivores," Noor says.

Given that ownership of the protected area has historically been contested between Egypt and Sudan, it is under intense scrutiny by the Egyptian authorities. Because of this, it is difficult to gain access to Gabal Elba as the authorities demand clearance from the intelligence services before allowing visitors in. The zone has been under the control of the Egyptian government since the 1990s.

According to Abdel Galil Hewaidy, an environmentalist and professor of geology at Cairo's Al-Azhar University, the Bishara tribe, who can be found across both Egypt and Sudan, once enjoyed freedom of movement. Since disputes over Halayeb and Shalateen intensified between the two countries, this freedom has lessened for the nomadic tribes.

"The border line was something that existed just on the map," Prof Hewaidy says. "People would move freely across these borders, and they would trade."

Towards the end of former president Hosni Mubarak's rule, as the zone become more disputed, Egypt gained more leverage over the area. This ended up limiting how people got around "as any sort of movement could be interpreted as political," Prof Hewaidy says.

Eco tourism in its future?

The heavy military restrictions make Gabal Elba "very very hard to get to," according to Noor who says this "is both negative and potentially positive because it could mean potential protection from tourism hunting".

Red Sea Governor Ahmed Abdallah, previously stated the Gabal Elba protectorate would soon be placed on "the environmental tourism map".

However, access to the protected area remains difficult as tourists have to get permits from Egypt's intelligence services before going.

Osama El Ghazaly, an environmentalist in the nearby Wadi El Gemal National Park, has not yet observed government action on tourism but said there have been a lot of youth-led initiatives over the past four years aimed at bringing visitors the protected area.

"Gabal Elba has a lot of potential. There is hiking, birdwatching, safaris and camping. Environmentally conscious tourism can really help the local communities there," El Ghazaly says.