In March 2015, Arab media reported that novelist Abdul Rahman Munif's library in Damascus had been vandalised and parts of it stolen. The renowned author of Cities of Salt, who passed away in 2004, had more than 10,000 books in his collection, including irreplaceable personal journals and manuscripts.

At first glance, news of the library’s theft seemed like another tragic outcome of the war in Syria. But the story of Munif’s library was more complicated than that.

Munif’s wife, Suad Kawadiri, issued a statement in April explaining the incident. While abroad she had allowed close family friends to stay at her Damascus apartment. When she returned, she found Munif’s library ransacked and her guests gone. Further details pointed to the involvement of a book collector who ran several repositories outside Damascus. Kawadiri felt helpless in the face of such loss, so she took her story to the press.

“Is Abdul Rahman Munif just nobody?” she asked in a Facebook message translated into English by Al-Araby Al-Jadeed. “Just because he does not have a citizenship, would he turn into nobody?”

Omar Nicolas, Kenan Darwich and Sami Rustom were all living in Berlin when they heard about Munif’s library. The Syrian trio had trickled into Germany over the past several years and formed the artist collective and publishing house Fehras Publishing Practices in 2015.

The case of Munif’s library seemed to touch on the collective’s interest in archiving and book publishing, so they decided to collaborate on a project, “When the Library Was Stolen.”

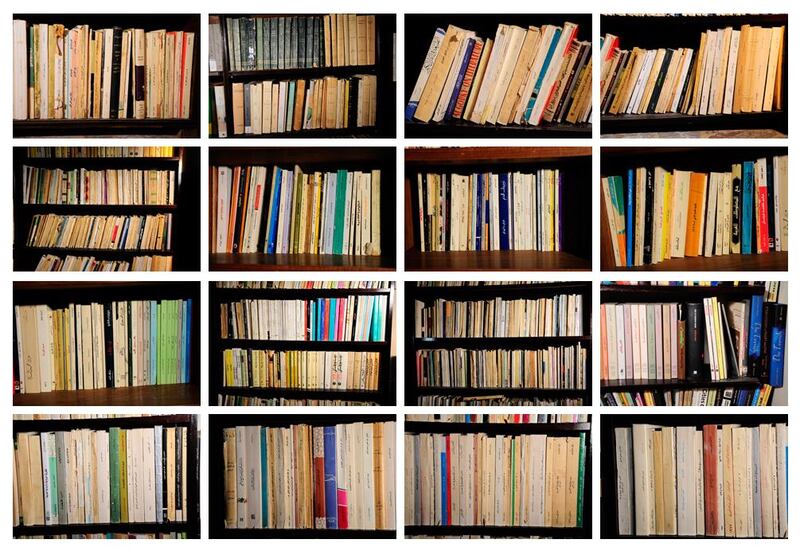

They arranged an opening exhibit in Berlin in June, displaying photographs of Munif’s remaining library alongside magnifying glasses to better examine the images: shelves upon shelves of titles on a staggering array of subjects, from poetry to military history.

The books represented an entire era of Arab intellectual history, even if parts of the collection were missing.

“The library of Munif reflects the history of publishing in the Arab world in the second-half of the last century,” said Darwich. “[It] contains valuable and rare books from the early 50s released by publishing houses from Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, Morocco and Sudan that no longer exist.”

The library represents the “nationalisation of publishing in the Arab world,” he said, when state ministries took over publishing ventures from private entities.

The Munif project will culminate in a September exhibition in Cairo, along with a book of essays “on the library as a space for cultural dialogue and a research source for history in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa,” said Fehras, responding collectively via email.

In the meantime, the members of Fehras are pursuing other projects that look at the displacement of archives in the region and what happens when publishing operations travel alongside the diaspora – not least because the artists themselves are a part of that diaspora.

Darwich, a publisher and curator, came to Germany from Damascus more than a decade ago to study at the Muthesius Academy of Fine Arts and Design. Nicolas, from Homs, is a book designer and performance artist. Rustom was the last to arrive in Berlin from Aleppo after working as a producer at a Damascus radio station and completing his BA in media studies; he now focuses on archival work. Munif himself was emblematic of an earlier era of roving artists in the Arab world.

Though often labelled a Saudi novelist, the Saudi government stripped him of his citizenship in 1963. Munif was born in Amman and then relocated to Baghdad, Belgrade and finally Damascus, where he would live until his death at the age of 71.

The theft of Munif’s library, according to Fehras, is “a reference for the displacement of libraries and books” in the entire region.

Had the library not been stolen, it might have remained an obscure, private collection. Its displacement made it part of a wider migration of books across the region due to war and conflict, part of what Fehras has labelled a “Series of Disappearances”.

The group’s forthcoming project looks at the role of flea markets and how they are instrumental in facilitating the spread of cultural knowledge throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa.

One of the most notorious book migrations, Fehras notes, took place during Lebanon’s civil war, when many of the country’s publishers and books found their way to Damascus, most notably among street vendors in the Salihiyah neighbourhood.

Fehras calls this the “arrival archive” and observes how the city became a hub for researchers looking for rare books.

Yet if Damascus, along with Baghdad’s Mutanabbi Street, were once major stops along the region’s book migration route, what happens when these are marginalised due to conflict?

Fehras observes that “many of these relocated libraries and documents are continuing their journey, or finding a new residence in a different world, rather than going back to their original places”.

The collective’s “Series of Disappearances” communicates that the dispersal of archives throughout the region during war is not necessarily a death knell for the printed word, but just a transformation.

In 2003, when United States forces stole Saddam Hussein's archives, The National reported that "hundreds of thousands of pages of the documents as well as transcripts of thousands of hours of covert voice recordings of top-level meetings" were taken from Iraqi ministries and libraries and moved to a research centre at the National Defense University in Washington, DC.

These age-old patterns of disappearance and migration can be traced back to Egypt, where legend has it that fires lit by Caesar’s army burned the ancient library of Alexandria to the ground in 391 AD. The library’s destruction was so epic that it has taken on the form of myth: the world’s largest repository of ancient knowledge obliterated.

In this cycle of destruction and creation, Fehras wonders how it can make its own work sustainable. Though artists from Syria began to create new work and receive funding at unprecedented levels after the outbreak of war, Fehras believes that many are at risk of being pigeonholed as crisis artists.

To address this concern, Fehras printed a collaborative publication with other artists titled Call For Applications! The book contains more than 100 interview-style questions, some of them cryptic –"What do you think about the colour red?" – and others more direct – "What does the term 'Syrian artist' mean?"

When asked the latter, Fehras responded that it does “not understand [itself] as a Syrian publishing house”. Artists from Syria must now contend with what Fehras calls a “new incomprehensible reality” that has “forced artists and cultural producers to build new relations to their surroundings, to time and space, and to life and death”.

Leah Caldwell writes for Alef Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and the Texas Observer.