In January 2009, the investment bankers, government officials and philanthropists attending the World Economic Forum in Davos got a blistering lecture from a most unlikely source. The first senior Chinese leader to attend, the premier Wen Jiabao, was known at home for his mild demeanour. Nicknamed "Grandpa Wen", he was popular in China for his down-to-earth style. Indeed, the Beijing leadership usually sent him out to handle natural disasters or other large-scale tragedies which called for a warm personal response. That genial grandpa was not in evidence at Davos.

Months after the Lehman Brothers collapse triggered a global economic crisis, Wen told the forum that the West was squarely to blame. An "excessive expansion of financial institutions in blind pursuit of profit", a failure to supervise the financial sector, and an "unsustainable model of development, characterised by prolonged low savings and high consumption" were behind the crisis, he said.

Wen's broadside was startling, but not unique. A decade earlier China had been largely absent from international relations. It barely played a role at the United Nations, for instance. Until the end of 2008 nearly every top Chinese official still lived by Deng Xiaoping's old advice to build China's strength while maintaining a low profile in international affairs. But by the early part of this decade, Chinese leaders had begun to assert themselves. As one current senior American official who deals with China said: "They are powerful, and now they're finally acting like it."

In the middle of last year, Beijing reacted to Japan's decision to impound a Chinese fishing boat in disputed waters by cutting off shipments to Tokyo of rare earth materials, a resource critical to modern electronic devices such as mobile phones. Beijing also warned Vietnam not to work with western oil companies such as ExxonMobil on joint explorations of potential oil and gas in the South China Sea; China had claimed nearly the entire sea for itself. When South-east Asian nations protested Beijing's stance and asked Washington to mediate their disputes with Beijing, Chinese officials reminded them, at a meeting of Asian nations held in Vietnam, that "China is a big country" - that it could outmuscle them.

Even with the United States, where China had trodden cautiously for decades, officials displayed a new-found assertiveness. In one article published in the state-run China Daily, a think-tank expert from China's Commerce Ministry wrote: "The US's top financial officials need to shift their people's attention from the country's struggling economy to cover up their incompetence and blame China for everything that is going wrong in their country."

Strangely, in the Middle East, a newly confident China seems essentially mute. This is despite the region's increasing significance to Beijing. China is now the largest importer of Saudi oil, intends to invest $100 billion in Iranian gas, and has become the world's biggest lender to developing countries, including many in the Middle East.

Even so, after the recent unrest in this region and the military intervention by a coalition of western and Arab forces in Libya, Beijing's leaders have said next to nothing. Hu Jintao himself has stayed silent, while China's vice foreign minister Zhai Jun has said only that the Middle East should solve its own problems. As Wu Sike, the top Chinese envoy to the Middle East put it: "There is no need. to think that as the US goes down, China will necessarily fill the void."

But China may have no choice but to fill that void. As it becomes the preeminent global economy with massive investments across the Middle East and thousands of Chinese companies operating in the region, it can hardly remain on the sidelines. China needs energy above all: it can little afford to alienate the publics of resource-rich countries that are now throwing out their rulers. By refusing to consider what a Chinese role in the Middle East might mean, Beijing's leaders are courting disaster when they might finally have to intervene.

The financial crisis left many western leaders wondering whether their political systems might contain deep, possibly unfixable flaws. The downturn, said the former US Deputy Treasury Secretary Roger Altman, left "the American model.under a cloud." By contrast, he believed, China's relatively unscathed position gave it "the opportunity to solidify its strategic advantages as the United States and Europe struggle to recover".

The West's flaws seemed especially notable when compared with what seemed like the streamlined, rapid decision-making of the Chinese leadership. China did not have to deal with such "obstacles" as a legislature or judiciary or free media that could question or block its actions. "One-party autocracy certainly has its drawbacks. But when it is led by a reasonably enlightened group of people, as in China today, it can also have great advantages," wrote the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman. "One party can just impose the politically difficult but critically important policies needed to move a society forward."

As the crisis continued, Chinese leaders stepped up overseas promotion of their authoritarian capitalist model. They launched training programmes in economic management for officials from other countries, courses which now attract some 15,000 foreign officials per year, primarily from developing nations in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. Beijing upgraded its international media outreach: today, according to its own figures, China's state-backed international television channel reaches over 65 million viewers outside the country. Beijing also launched Confucius Institute programmes on Chinese language and culture at universities from Uzbekistan to Tanzania. China also vastly expanded its foreign-aid programmes. By 2010 it had surpassed the World Bank as the largest lender to developing nations, particularly in Africa, the Middle East and South East Asia.

This soft power came with a harder edge. At international assemblies such as the United Nations and the G20, Chinese officials started to speak up. They pushed for the replacement of the dollar as the world's reserve currency, argued for growing cooperation among powerful developing nations like India, Brazil and Russia. At global climate talks last year they held a closed-door session with a number of other nations that Barack Obama had to burst into, uninvited. This year, China's defence budget will rise by nearly 13 per cent, and the Chinese military has repeatedly shocked its neighbours by launching submarines and other vessels unsettlingly close to their shores.

According to many Chinese officials, the Middle East is critical to Beijing's global coming-out party. With minimal domestic oil and gas resources and an economy growing by nearly 10 per cent each year, China has become desperate for energy. Its state-controlled companies are willing to pay whatever price is necessary to secure it. China now purchases more than 50 per cent of its oil from the Middle East, and rising fuel prices across China, a major cause of protests in the country, make the Chinese government even more determined to lock up supplies.

Even beyond oil and gas, the Middle East holds enormous promise for China. Beijing has built a close strategic relationship with Turkey, launching military exercises together now that Turkey's military partnership with Israel has waned. China has become a major supplier of arms to Iran and other countries in the region. Chinese companies have had a difficult time getting a foothold in developed markets, where their lack of brand names and reliability has hurt them. Instead, they have been encouraged to focus on developing markets, in nations where there is less competition from major western or Japanese brand names, where the cheapest products often win, or where corruption, political risk, or human rights abuses deter western firms.

Two years ago, China became the largest trading partner of Africa, including North Africa. Even as hundreds of thousands of protesters gathered in Cairo and other cities and western companies evacuated their employees, several delegations of Chinese companies refused to cancel their visits to Egypt. In Sudan, where many western companies cannot invest because of sanctions imposed by their governments, Chinese firms dominate the local markets. Local vendors sell Chinese-made mobile phones, stereos, cooking utensils, and nearly any other manufactured product.

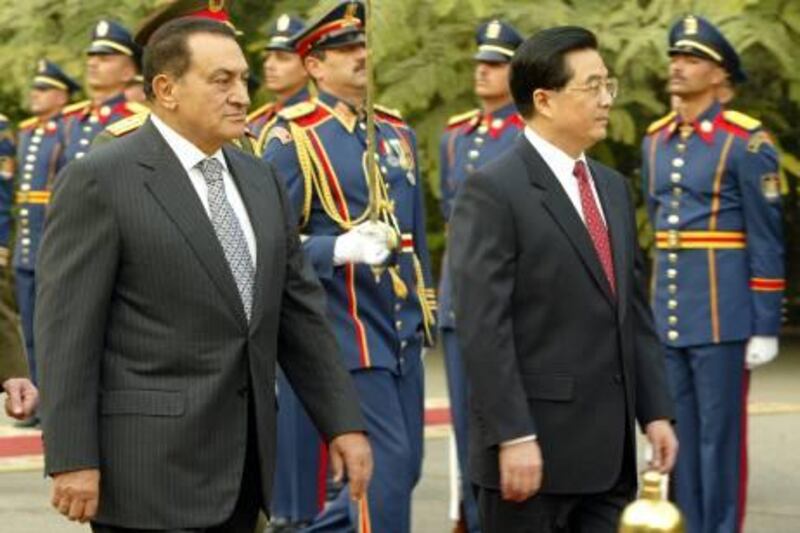

During trips to the Middle East by top Chinese leaders, Beijing's enormous potential clout has been on display. When the Chinese president Hu Jintao arrived in Egypt in 2004 for an official visit, then-president Hosni Mubarak gave him a regal welcome. Together, the two leaders reviewed a presidential guard, and then the Arab League's secretary general, Amr Moussa, eagerly tried to sell the Chinese president on the idea of a Sino-Arab organisation that would help other Arab states woo Chinese aid and investment. The Chinese turned on their charm, too; by September, a Sino-Arab forum was up and running, and after Hu's visit, a cavalcade of other senior officials arrived in Cairo for meetings with Mubarak and his aides.

For all of China's growing sophistication in international affairs, Hu Jintao has said less about the unrest that began in Tunisia last winter than Silvio Berlusconi, leader of a declining economy with 60 million people. Senior Chinese leaders have declined to comment on potential threats to Saudi Arabia, its major oil supplier. They have been silent on rising discontent in Sudan, where their firms dominate the oil industry and conflict looms over how to divide petroleum revenues after the south secedes. According to American officials, China has largely avoided multinational conference calls designed to strategise about Libya's civil war or to plan for shifts in the power structure in the Arabian Gulf.

Why has Beijing responded so little? In public, Chinese leaders say that their official view of the world demands they keep a low profile. They are pledged to a policy of "non-interference" in which countries respect each other's sovereignty and do not meddle in others' affairs. And, after all, from the US's involvement in the Iranian coup in 1953 to America's decision to boycott the results of the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections, decades of western intervention in the Middle East have rarely produced happy results. And yet, China has readily abandoned its policy of non-interference in other circumstances. Just ask Vietnam.

One underlying reason for China's reticence may be that its leaders don't want their people to get any ideas from the unrest in the Middle East. When an anonymous group of Chinese protesters posted a call online in late February for a "Jasmine Revolution" mimicking the Middle East demonstrations, Beijing cracked down hard. State security officials beat up foreign journalists attempting to cover one planned protest, shut down Chinese news outlets that attempted to report on the Middle East unrest, and filtered the word "Egypt" out of the Chinese internet.

Yet the Chinese Communist Party is not Muammar Qadaffi. It enjoys support for its decades of wise economic management, and its leaders could very well win a free election in the country. One recent poll by the Washington-based Programme on International Policy Attitudes, found that 63 per cent of Chinese respondents said their government's efforts to address the global economic crisis were "about right". Of all the countries surveyed in the poll, China was the only one where a majority of citizens believed their government's response to the crisis was correct. And some Chinese hawks, posting on nationalist blogs and chat rooms, have pushed the Beijing leadership to become far more aggressive in the Middle East, as a great power might. In one tiny sign of assertiveness, Beijing sent four naval frigates in early March to Libya to rescue thousands of Chinese workers, China's first deployment of forces into the Mediterranean.

All the same, Beijing's leaders today are remarkably weak - far weaker than many outsiders realise, and far weaker than their hypercharged economy and strident rhetoric at international events like Davos would suggest. In the 1980s and 1990s, two powerful and charismatic leaders, Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, dominated Chinese politics. Deng, a veteran of Mao's Long March and the originator of the economic reforms that launched China's boom, enjoyed enormous respect in the military, the Party and other centres of power. Though not as dynamic as Deng, Jiang, another Party veteran and notable reformer, had solid control of China's power blocs and close allies within the People's -Liberation Army.

China's current leader, Hu Jintao, is a mere cipher by comparison. He rarely deviates from a script in public events. He has never led any battles or launched any major reforms. Other top Chinese leaders, including Hu's probable successor Xi Jinping, enjoy even less credibility within Beijing's power elite. Chinese leaders "are becoming weaker and society stronger," says the China scholar David Lampton of the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Indeed, with an authoritarian leadership that lacks a powerful centre and a growing number of voices influencing policy-making, Chinese government can become almost paralysed - the exact opposite of the streamlined, fast-acting dictatorship that Thomas Friedman praised. "Even if the centre wants to control Chinese security and foreign policy in detail, it may not always be able to do so," Lampton claims.

Meanwhile young, middle-class, nationalist hawks, the kind of men and women who celebrated China's Libya voyage, have become more strident on the internet. In one famous case, an online video called "2008 China Stand Up!" portrayed China battling the West in a new Cold War. The video quickly attracted millions of hits. And despite perceptions outside China that Beijing does not have to bow to public sentiment, the government, weaker than in Deng's time, frequently does bend to this nationalism. Beijing took a fairly soft line on Tibet's 2008 anti-China protests, for instance, until nationalist bloggers blasted the leadership's timidity. Then Beijing cracked down hard - in part, officials say, because of the harsh response to their initial strategy.

The hawkish People's Liberation Army has become another powerful voice in the absence of strong leaders. At a major international forum in Singapore last year, a top Chinese general lambasted the United States, while the US secretary of defence Robert Gates looked on. Urging a milder stance is China's foreign ministry, which often seems uncomfortable with Beijing's more forceful policies. The foreign ministry knows that China still lags far behind the reach of the United States or even France in the Middle East: the region is considered a much tougher posting for Chinese diplomats than places like East Asia, where there are local Chinese communities and Chinese schools.

With the foreign ministry, the army, civilian nationalists and other power groups at odds and no real ability to mediate disputes, Beijing frequently seems to be delivering two conflicting messages at once. At the same time that its leaders were decrying foreign intervention in the Middle East and telling Middle Eastern nations to handle their problems themselves, Beijing voted for a Security Council resolution imposing sanctions on Muammar Qadaffi's regime. This is the kind of tough approach that Beijing supposedly does not support.

The question that China will soon face is whether it can afford such indecision. As Chinese companies expand their foreign investments, thousands - even tens of thousands - of Chinese workers will arrive in places that could eventually be centres of unrest. They will go to Iran, Sudan and Algeria, Libya, Egypt and Yemen, countries where high unemployment makes foreign workers a target for popular anger. The Chinese government's claim of non-interference has failed to protect Chinese labour in the past.

When demonstrators rose up against Qadaffi last month they attacked Chinese workers, just as they targeted other foreign workers whose firms, they believed, were helping his regime. In many previous examples, across Africa and Asia, local people also have targeted Chinese workers. In Zambia last year, these protests spiralled into bloodshed. Guards at one Chinese owned coal mine opened fire on local demonstrators.

In Myanmar, altercations between nationals and migrant workers devolve into beatings, kidnappings, or worse almost every day. In Mandalay, as many as 100,000 Chinese business people and workers have arrived in recent years, setting up shops throughout the dusty, baking-hot central business district. "The government might be close to China, but average people are angry at all the Chinese workers coming into [the country]," said one dissident.

The worst-case scenario is that, by neither choosing the interventionist approach that the West has taken towards the Middle East nor truly sitting on its hands, Beijing risks alienating both current rulers and protesters demanding change. This would leave it with no allies in the region.

Some anti-China sentiment already has begun to coalesce. In Iran, during the Green Movement protests two summers ago, anti-government demonstrators gathered not to chant the usual "Death to America" but instead "Death to China". They knew that Beijing had built a close relationship with Tehran. At the same time, fearing that strong ties with Iran could cost China elsewhere, Beijing has on occasion snubbed Mahmoud Ahmedinejad. Indeed, when Ahmedinejad attended a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a regional group linking China to Central Asia and the Middle East, Chinese senior officials pointedly avoided him, infuriating the Iranians.

China's regional paralysis may be bad for China, but in the long run, it will also be bad for the Middle East. Without any coherent policy in the region, Beijing may find it extremely difficult to understand the new generation of Arab-Muslim politicians that will come to the fore in the wake of this year's uprisings. Such a situation could slow down trade, investment, aid, and all the other aspects of a burgeoning relationship with China. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, a country where Beijing has made significant investments, last year's government-toppling uprising left China looking puzzled, unsure of how to handle the country's new, more open leadership.

What's more, whether or not Middle Eastern nations want to copy China's model of development, having another major power engaged in the region would provide a balance to the West, and could possibly allow Middle Eastern nations to play both powers off against each other. In South East Asia, savvy nations like Singapore and Thailand have already done exactly that, welcoming Chinese investment and diplomatic ties while simultaneously using the threat of China's expanding power in the region to keep the White House interested and obliging. It's a lesson the Middle East's new leaders would do well to study.

Joshua Kurlantzick is Fellow for South East Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

China lacks focus in the Arab world, missing a mutual opportunity

As China's involvement in the Arab world increases, new political and economic tensions continue to be revealed. However, these developments may also provide a vital balance to existing western interests in the region.

More from The National