“Tapes have never been weird for me at all,” says Brian Shimkovitz. “I grew up on the cusp of the CD and cassette era, and have always had hundreds of them in my own collection.” Rather than a simple fact of life for a music fan of a certain age, though, the compact cassette has become a defining passion for this 33-year-old. As the proprietor and curator of the aptly named website Awesome Tapes from Africa, he has spent the past seven years straddling the boundaries of analogue and digital distribution, opening up a continent’s worth of music to listeners across the globe.

“I’ve always been a music nerd,” he explains. “When I grew up, I played the drums and was really into jazz. That led to me studying ethnomusicology at Indiana University. While I was there, a friend of mine played me a bunch of tapes that he’d picked up while he was learning about drumming in Ghana. That really fired my interest. I’d never travelled abroad at that point and then the opportunity to take a semester overseas came up. I decided that I wanted to go somewhere really far away and one of the options I was given was an arts and culture programme in Ghana.”

Certain strands of West African music – including the intricately rhythmic guitars of Ghanaian highlife stars such as Ebo Taylor and E T Mensah – have long been popular in the United States and Europe, but, arriving in Accra in 2002, Shimkovitz was immediately captivated by what he heard on the city’s streets. “I thought I’d be spending a lot of time listening to those kinds of highlife artists,” he says. “But I found out really quickly that there were all kinds of things happening with rap and hip-hop that weren’t getting heard outside the country.”

Shimkovitz spent his time in the Ghanaian capital digging into these contemporary sounds, but just a few months later, he had to return to the United States to finish his degree. As soon as his studies were completed, though, he made a successful application for a Fulbright grant and returned to Ghana in 2004 to research an infectious fusion of highlife and hip-hop, known as “hiplife”. “CDs were expensive for people then, and many didn’t have the means to play them, so there were a lot of cassettes in urban Ghana,” he says. “I dove headfirst into them, visiting stores, finding out what people were into and picking up as many of them as I could.”

While his time in Africa was relatively short, Shimkovitz’s obsession with its music would prove altogether more enduring. Two years later, while working in public relations in New York, he hit on a simple idea. Like many people with a little time and lot of enthusiasm for a particular subject, he went online and set up a blog. He began to upload digital recordings of the music that he had discovered on his travels for readers to download, free of charge. Accompanying each entry was explanatory text in relaxed, approachable prose and colourful scans of album-sleeve art. His site became an unexpected hit.

“I kind of needed a hobby at that time and I really wanted people to hear what African music sounded like in Africa,” he says. “The kinds of things that labels in the US and Europe were not really releasing and that weren’t very easy to come across. When I first started to put the music online, I’d sometimes do a search for the artist or the name of the tape and I wouldn’t find anything. A lot of it was un-Googleable and I found that fascinating.

“I kept on doing it on the weekends, just for myself really, but then I began to run into people around Brooklyn or I’d get emails saying thanks. They would often tell me that they had always really liked African music but that it was such a big area that they felt a little shy about diving into it, but that what I was doing had inspired them to look a little deeper, or that they were just happy that someone was making this music available to them. I think it definitely helped that I’d always had a pretty un-encyclopaedic approach to what I was doing and had tried to be as open and unpretentious as I could.”

Over the years, Awesome Tapes has grown exponentially, both in terms of its popularity and the breadth of its coverage. Shimkovitz has made trips to a variety of countries to buy music, but he also shops in African diaspora communities closer to home and receives contributions from a global network of fellow enthusiasts. The artists featured on the site are too numerous to count and the diversity of styles bewildering, but my personal favourites include the Congolese jazz of Franco, the Ethiopian lounge-room grooves of Woubeshet Feseha and the Ivorian country of Jess Sah Bi & Peter One. When asked how many nations Awesome Tapes has visited to date, Shimkovitz replies: “It’s difficult to say. Twenty, 30 … nowhere near all of them and not nearly enough.”

The use of cutting-edge digital technology to pay homage to a largely redundant analogue technology may seem, at first glance, somewhat ironic, but Shimkovitz disagrees. “I’ve always loved the democratic nature of tapes,” he says. “Before, music distribution was largely controlled by record companies and to release your music on vinyl, you either had to have really good connections or a lot of capital. Tapes levelled that playing field. They were like the original MP3s – cheap to produce and something that could be duplicated and shared among people. I wanted to do something with the internet that brought those ideas together.”

Beyond the music that it contains, Shimkovitz also believes that the cassette possesses a powerful significance as an artefact. “I’m really into digital technology, but sometimes people want and need a physical product,” he says. “Even now that we have the internet and plenty of other ways to distribute music, if I visit a Nigerian shop in New York, you can still find people selling tapes. They’ll be sold alongside clothes and food and spices from home, in places where people from that community congregate. They’re a way of holding onto identity and culture and a way to keep in touch with family and friends.”

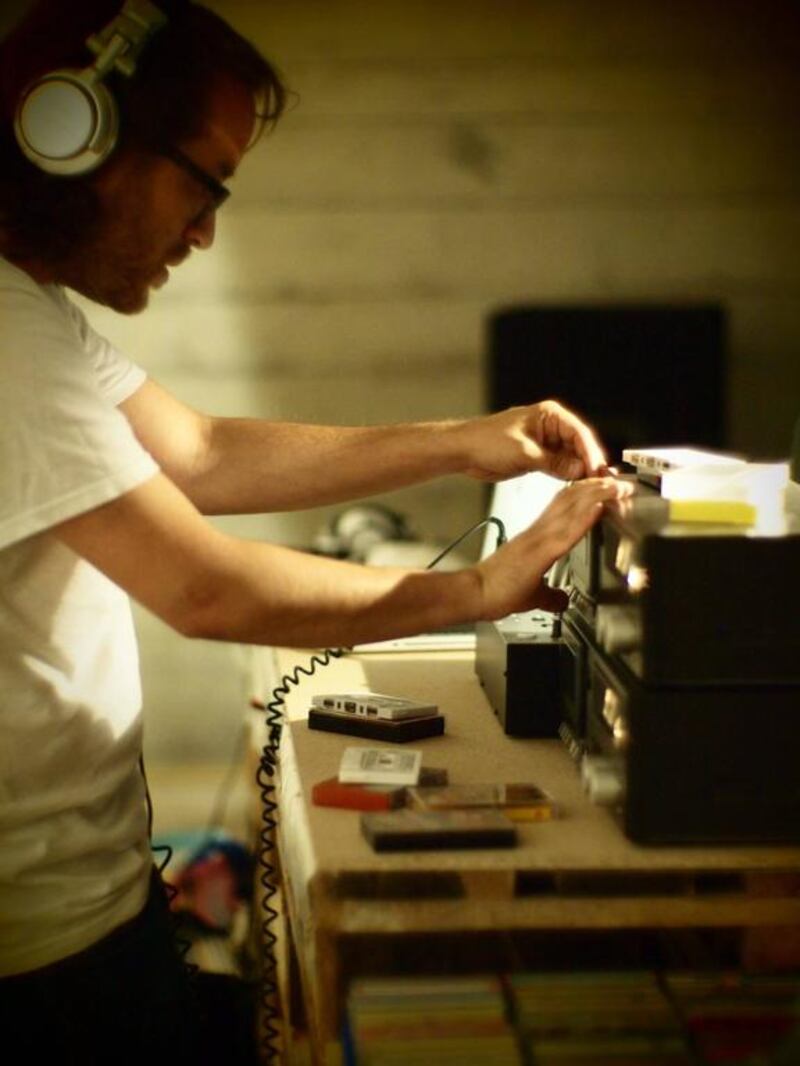

Shimkovitz’s work also extends beyond the computer keyboard and into the real world. Now based in Los Angeles, he has become an in-demand DJ, playing upbeat sets on cassette to audiences across the US and Europe. “I like making people dance,” he says. Since 2011, he has also taken on the role of label boss. In this time, the Awesome Tapes imprint has released works by artists including the Malian singer Nahawa Doumbia, Somalia’s Dur-Dur Band, the Ethiopian synthesiser player Hailu Mergia and the South African Shangaan disco of Penny Penny. With this increased visibility comes a greater sense of responsibility, but that’s something that Shimkovitz appears comfortable with.

“There are definitely ethical issues involved with making people’s work available for free on the internet,” he considers. “When I can work directly with artists, I deal fairly with them and make sure they get paid. With all the other music I post, I try to make sure it’s represented well and not as something strange or exoticised. When I was in Ghana, a lot of artists would ask me how they could build an audience in the rest of the world. I couldn’t really give an answer to them then, but when people started coming up to me and telling me how much they liked certain things I’d posted on the site, I realised that the world was a much more fertile and open place for this kind of music than I’d previously imagined. Since then, some of them have had their first American and European shows. I don’t want to take credit for that in any way, but if what I do can help to gain a little recognition for these artists and help them on their way toward their goals, then I’m really happy.”

• Visit www.awesometapes.com

Dave Stelfox is a photographer and journalist. He lives in London.