Picture the scene. A skinny teenager and his best friend stand mesmerised in a suburban garage. Their mouths have opened, automatically, in reflex awe. Before them sits a shiny red car. But not just any car. "The 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California," says the skinny teen. "Less than a hundred were made. My father spent three years restoring this car. It is his love. It is his passion." The best friend slides slowly towards the car and, hinting at the wild Ferrari-driving adventure to come, gives a little cocky shrug, "It is his fault he didn't lock the garage!"

The scene, of course, between Matthew Broderick and Alan Ruck, is from the 1986 John Hughes classic, Ferris Bueller's Day Off. It is the set-up for a movie that will use this same car both as a mode of transport, a symbol of liberation and a metaphor for the troubled relationship between Ruck's Cameron and his overbearing yet unseen father. In other words, it speaks deeply to American cinema to wider American culture and to the emblematic power that resides in the humble automobile. And yet as the current recession bites and begins to pulverise the US automotive industry, it might also be a scene, and a movie, that in the coming years will look increasingly antiquated.

The prognosis for the American automotive industry is not good. Since the US senate's rejection of the so-called bailout plan for the three brand leaders - Ford, Chrysler and General Motors - the possibility, say the experts, of a triple bankruptcy remains. Iif the unthinkable happens, it may well precede a seismic shift in how automobiles are regarded in the United States. The car, of course, is synonymous with the United States. In their definitive tome The Automobile and American Culture, the editors David L Lewis and Laurence Goldstein outline in detail the deep-rooted connections between the wide-open spaces of America and the cars that were invented to traverse them. Here, it's worth noting that the epic and historically significant phrase "Trans American" (immediately recalling the early wagon-trail years) was ultimately abbreviated into the name of that most iconic of screen cars, GM's Pontiac Firebird Trans Am - see the zany smash-and-crash Smokey and the Bandit series, plus TV's Knight Rider. Elsewhere, the strip malls, the youth culture and the existence of suburbia itself was only made possible through the freedoms provided by car travel.

Nonetheless, it is cinema alone that has provided cars with both their perfect platform for promotion and their perfect outlet for expression. Indeed, according to the movie legend Cecil B DeMille, the relationship between cars and cinema is an intensely symbiotic one, in which both forms "reflected the love of motion and speed, the restless urge towards improvement and expansion, and the kinetic energy of a young, vigorous nation". The two industries, thought DeMille, shared the same cultural chromosomes. And indeed, as any brief montage of silent era cinema will reveal, there weren't many early motion pictures that could not be improved by the addition of a speeding Model T Ford (preferably one overloaded with Keystone Cops).

Similarly, the Cadillacs, Fords and Studebakers that litter the gangster movies of the 1930s and 1940s were more than just integral to mood, setting and story. They were desirable and glamorous in themselves. Movies such as Scarface and The Public Enemy so clearly celebrated the iconography of gangsterism - the hats, the coats and, most especially, the sight of a tommy gun sticking out the back window of a V16 Cadillac - that they were partially responsible for incurring the wrath of moral guardians and forcing a proscriptive moral code of conduct, the Hays Code, upon the industry.

It wasn't until the 1950s and 1960s, however, that Hollywood really began to celebrate its cars in loving and detailed close-up. Films such as the 1964 melodrama The Yellow Rolls-Royce starred Rex Harrison, Shirley MacLaine and Ingrid Bergman in a story about separate characters who each have a brief ownership of the talismanic and titular car. The Roller, naturally, was the real star. The movie was a modest hit. But the "car as star" phenomenon had taken hold. Soon Herbie came along in The Love Bug, the first of four Disney movies about a Volkswagen Beetle with a mind of its own. There was Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, too, a hybrid vehicle of no particular brand but one that could nonetheless fly and float at will.

The car as star was also a horror villain, appearing in both Christine (it was a madly possessive bright red Plymouth Fury that happily ran over non-car-enthusiasts) and the 1977 chiller The Car. The latter film, starring James Brolin, Kathleen Lloyd and a demonic homicidal Lincoln, features the classic Jaws-inspired moment when Lloyd's terrified Lauren stands in her kitchen on the phone to Brolin's Wade and whimpers, "Tell me what to do! I'm scared! I, I?" She then hears a car engine, and turns to her kitchen window just in time to see the Lincoln leap free from the ground and crash in on top of her.

All these movies, no matter how derivative, seemed to be articulating and expressing doubts and confusions about the pre-eminence of the car in modern American life. Certainly, John Carpenter's Christine (an adaptation of a Stephen King short story) unfolds like a morality play, warning adolescent American boys about the dangers of car obsessions (as, much later, David Cronenberg's Crash would chastise adults for losing touch with their humanity, and falling for their machines).

Nonetheless, the car as star is still found today in movies such as Transformers, where a canary yellow Chevrolet Camaro turns out to be one of a superior race of humanoid machines. He can fight, run and aid his teenage owner, Sam Witwicky (Shia LaBeouf), with courtship and other adolescent endeavours. The difference, of course, is that in modern movies, where the practice of product placement is so rife, the car as star has become a direct advertisement rather than a quirky narrative device. And certainly, in the opening sequence of the recent Bond movie, Quantum of Solace, there is little to distinguish the action therein from a glossy Aston Martin commercial. The same can be said for the Lamborghini in The Dark Knight, the BMW in GoldenEye or Will Smith's Audi in I, Robot. In each case, the symbolism and the narrative function of the car struggles hard against its own branding - Smith's Audi, especially, is repeatedly photographed from in front of the trademark grill, leaving audiences in no doubt as to the commercial nature of the sequence.

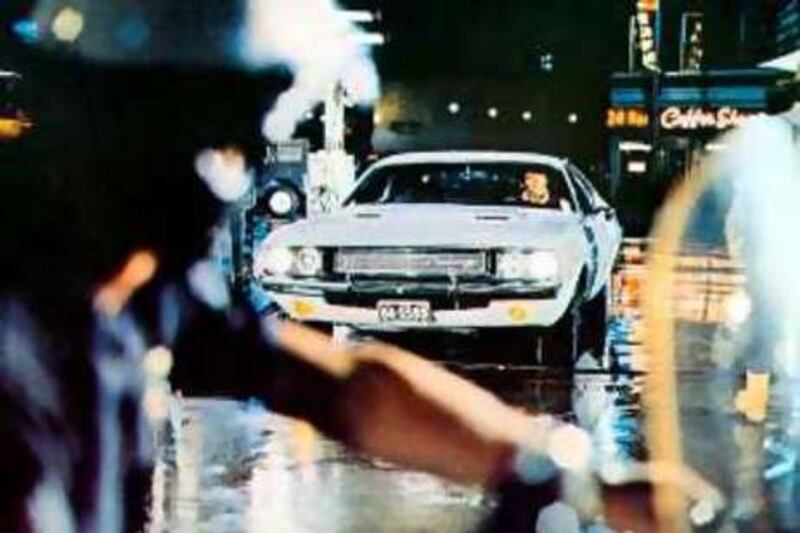

Just as films such as Christine spoke about the prevalence of car obsessions in everyday American life, it seems perhaps fitting that Smith and Bond leave us in no doubt as to the dominance of, not cars, but marketing as the prime cultural influence in our own era. Naturally, it's not all about star cars and branding overdrive. The movies have retained a fundamental respect for DeMille's audience-pleasing ideas of motion, speed and kinetic energy. The French Connection, Bullitt, The Cannonball Run, The Gumball Rally and Smokey and the Bandit are all movies that use cars, exclusively, to orchestrate action with a capital "A". They are surrogate roller coasters for speed-seeking audiences, and the favoured shot here is the camera mounted on the car front, allowing the viewer that highly pleasurable yet vertiginous point-of-view experience. These kinetic-overdrive movies have modern counterparts in films such as The Fast and the Furious franchise, or Gone in 60 Seconds, or the recent Death Race, or even Speed Racer.

The common connection between these race-obsessed movies is a sensory one. These films are about the noise of engine roar, the cleverly cut close-up of the speeding wheel, the gear change and the asphalt slipping underneath the bumper at breakneck speed. And yet, as the hot-rod obsessives in American Graffiti (George Lucas's pre-Star Wars movie about 1950s high-schoolers, racing pumped-up vintage cars) reveal, there is still something fundamentally American about this particular automotive fantasy. Why, for instance, despite some honourable exceptions (the recent French Taxi franchise, in particular) are there so few European car-chase movies? Is it because non-American cinema has a less literal understanding of the word "action" and, consequently, a broader definition of what constitutes "drama", ie which is more thrilling - watching two hot rods chase each other down Hollywood Boulevard in The Fast and the Furious, or wondering if a nervous East German playwright is going to be exposed in The Lives of Others?

The answer, one suspects, is that car culture has become so ingrained in US citizens, and car action so familiar in American cinema, that any alternative for mainstream action is rarely contemplated. Thus the shocking prospect of the collapse of the US automotive industry, though difficult to contemplate, might one day lead to an even more incredulous and mind-blowing reality. We might have Hollywood movies that are free from branded car commercials and endless car chases, and full instead, of drama, emotional intrigue and action, with a small "a".