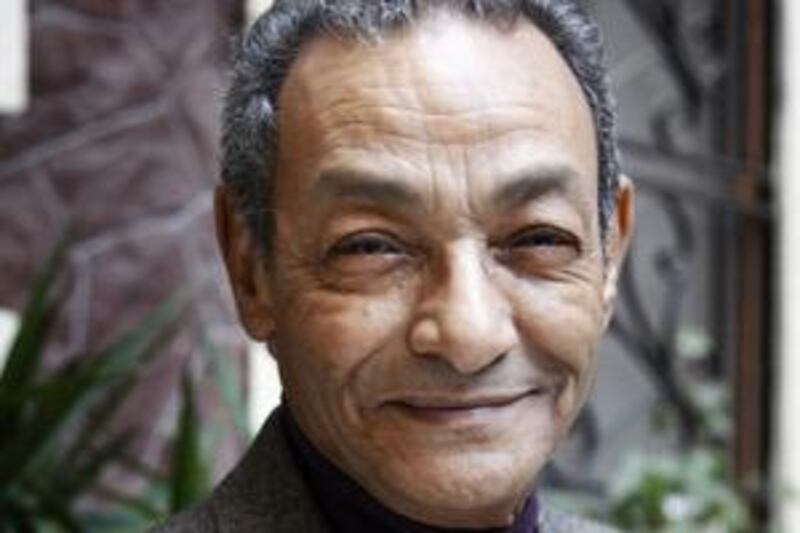

The Egyptian novelist Bahaa Taher is in London for the UK launch of his most recent novel, Sunset Oasis, winner of the inaugural International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2008. We meet at his hotel in Regent's Park, in a plush lounge at the back. Taher has spent the morning being interviewed by the BBC's World Service and seems a little tired and frail - he is 74, after all. But he is in good humour, dismissing my apology for using a clunky old cassette Dictaphone with a wave of his hand. When he began his career, on Egyptian Radio's cultural programme in the 1950s, enormous reel-to-reel machines were the order of the day: "That," he says, pointing, "seems to me the height of modernity."

Taher has long been celebrated in Egypt - a totemic figure on a par with such writers as Naguib Mahfouz and Youseff Idriss. But Sunset Oasis, which beat 131 other novels from 18 countries to the $60,000 (Dh220,000) award its author calls "a very welcome surprise", should secure him the international readership he deserves. Its excellent English translation - by Humphrey Davies, who also translated Alaa Al Aswany's hugely successful The Yacoubian Building - was funded by the Tetra Pak heiress and owner of Granta magazine, Sigrid Rausing.

Set in the late 19th century in the oasis town of Siwa on Egypt's Libyan border, Sunset Oasis is a powerful, frequently haunting fable of betrayal and occupation. Mahmoud Abdel-Zaher, the main protagonist, is Siwa's chief of police - hardly a dream job. Siwa is a rebellious Berber outpost whose leaders have killed two of Mahmoud's predecessors. But Mahmoud has no choice; he has effectively been banished there for showing disloyalty to the British regime in Cairo. Perhaps the situation would be simpler if his Irish Catholic wife, Catherine, stayed behind. But she is determined to follow him and be transformed by the harsh exoticism of the desert; also to pore over the local archaeological sites, especially the temple of the Oracle of Amun (visited by Alexander the Great in 331 BC after his conquest of Egypt), even if her efforts alienate the local community and endanger her and Mahmoud.

Taher says he was inspired by the story of the real-life district commissioner of Siwa in the last years of the 19th century, Mahmoud Azmi. As his partial namesake does in Sunset Oasis, he performed, in 1897, an act of cultural vandalism so bizarre that Taher decided to devote an entire novel to rationalising it. "I tried to learn more about Mahmoud Azmi," he says. "I read everything I could about Siwa and the western desert, but I couldn't find anything. So I had to invent a character like him. But the character alone wasn't enough for the novel, so I had to invent a wife for him. Then I thought about what his background would be. If he was about 40, then he was living during the 1882 Orabi Revolution against British occupation, so he would have taken a position either for or against."

Formally daring, Sunset Oasis is structured as a sequence of monologues by its main characters, including Mahmoud, Catherine, Sheikh Saber (one of the Siwan tribal sheikhs) and, wonderfully, Alexander the Great himself, who intervenes to clarify and supply historical context. "I tried writing the novel in the third person like a normal novel," Taher says, "but it refused to be written like that. Each novel should have its own voice. And here" - he laughs - "here, even Alexander the Great wanted to have his voice! It might seem pedantic, but I believe that you don't write novels: novels write you. They have a life of their own and want to be written the way they feel is apt."

Sunset Oasis is a historical novel, for sure, but it is never bogged down by detail. It is also, in translation at least, idiomatically modern. "This is an important question," says Taher, "because what do we mean by 'historical novel'? I did a lot of historical research, but I never felt that I had to be 100 per cent true to history. I felt free to use history to my own ends. For instance, when Mahmoud says that two of his predecessors were killed - no, that's not true. In real life they were persecuted but not killed. But I felt that they had to have been killed in order to make the threat to Mahmoud's life feel more true."

Catherine is a fascinating character: a satirical target, in one sense - she stands for all that's crude and naive about western attitudes to the Arab world - but undeniably an entry point to the novel for Western readers. Taher says he is proud of her contradictions; that they make her the opposite of a stereotype: "Of course, Catherine does not see herself in that light. She sees herself as an agent of advancement, as someone whose job it is to expose Egypt's history to itself. When a character has this kind of contradiction, she becomes a rich character - at least I hope she does. Mahmoud is the same. He is conscious of his own contradictions, which differentiates him from others who are also contradictory but don't know it."

You sense Taher is happy to toy with western expectations: he disapproves of what he calls "exotic novels" about terrorism, oppression and infighting among minorities by "certain writers who write with their eyes on western readers, on translation. It's very easy to be popular like that." Bahaa Taher was born in Cairo in 1935. His father was a school- teacher. His illiterate mother spun wild stories about her childhood home near Luxor. He studied literature at Cairo University and worked in radio, devoting any spare time to experimental writing and left-wing political activism."It was a period full of optimism and the feeling that we were going to change the world tomorrow," he says. "So you can imagine the disappointment and disillusionment that followed."

Concerns that he was at the centre of a "red cell" at Egyptian Radio led to his expulsion from the country by Anwar Sadat in 1975. Taher settled in Geneva, Switzerland, where he became a United Nations translator, but returned to Egypt in 1995. He now lives in Zamalek, an island on the Nile, with his Greek-Slovenian wife, Stefka, a Russian interpreter. Taher's enforced exile was, he says, an extremely difficult period. "For two years, I wasn't able to write. Partly because I was busy, but also because man is like a plant. He needs his own earth and blossoms in it. If you take him and transfer him to different soil, either the adaptation succeeds - which needs a lot of work - or it doesn't, but in both cases the plant will be different." Although Taher had been writing stories since 1964, his first novel, East of the Palms, wasn't published until 1985. He writes slowly, he says: "You have to take the manuscript from me by force because I rewrite, rewrite, rewrite."

Since East of the Palms there have been five other novels, the best known of which are 1991's Aunt Safiyya and the Monastery, about a young Muslim man who seeks sanctuary in a Coptic monastery, and 1995's controversial but much praised Love in Exile, which dealt with the Israeli massacre of Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut in 1982. That Love in Exile won an award in Italy pleased Taher hugely: "It runs contrary to the mainstream of writings about the Middle East in the western world, so if people can read it and like it to the point of giving it a prize, it makes me very satisfied." This statement begs the question of whether he means that it is hard to write about Israeli violence without being accused of anti-Semitism. "Of course," is his simple reply.

When I meet Taher, his visit to London coincides with that of Israel's prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who is in the city to meet his British counterpart Gordon Brown and the US special envoy George Mitchell, and discuss the resumption of Middle East peace talks. British newspapers are full of optimism; Taher less so. "Let us wish them luck and hope that Mr Obama is really the man to change the situation," he says. "But I have my own doubts because the balance of power in the region is not at all on the side of the Palestinians."

I wonder if Taher still considers himself a radical? He thinks carefully before replying. "I am still against the same things I was against when I was young: social and political injustice, especially against women or people of different origins or ethnicities. What's different is that the hope I had at one time no longer exists. Hopefully things will change - but not, I think, very quickly. "Generally speaking, I think that the less western interference there is in the affairs of the Middle East the better. But unfortunately that's not how people think here [in London]. They think more involvement is better."

Sunset Oasis is published by Sceptre.