The Western conjures up many images: the cowboy, the sharp-shootin' gunslinger, the lawless American frontier with its scorched, dusty vistas. There are the classic films, of course, starring John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. An entire genre has survived on Wild West cliché, which is probably why tales of grizzled, Stetson-wearing heroes are rarely the stuff of prize-winning literature.

Until now.

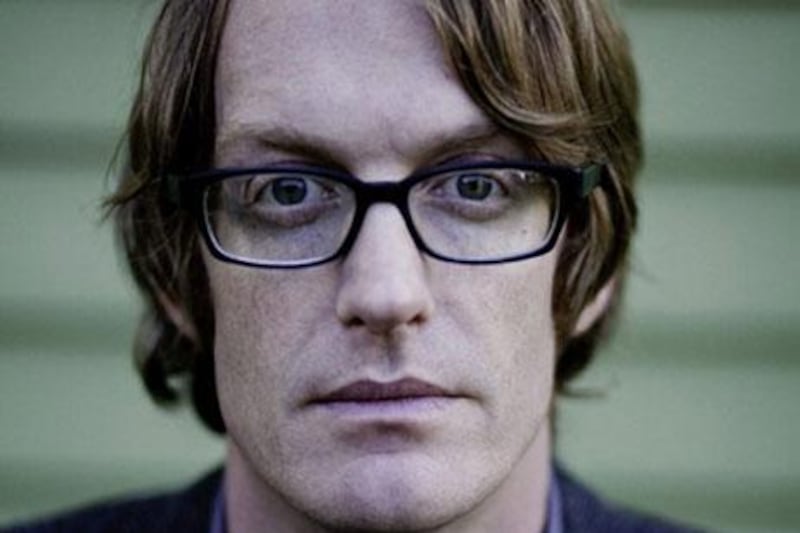

On Tuesday, Patrick deWitt will find out whether his second novel, The Sisters Brothers, has won him the prestigious Man Booker Prize. Up against established novelists such as hot favourites Julian Barnes and Carol Birch, deWitt is one of the outside bets, but that's hardly a surprise. Incredibly, his tale of a reluctant assassin roped into one last job by his brother during the 1851 Gold Rush, is the very first Western to be shortlisted in the award's 42-year history. And yet deWitt isn't some lasso-wielding apologist for the genre. In fact, the 36-year-old Canadian, now living in Portland, Oregon, was keener to subvert all the clichés than play to them.

"Not maliciously, but mischievously - I wanted to topple the whole thing," he says. "But one of the really fascinating byproducts of writing The Sisters Brothers was that I came away with a real respect for the Western. It stopped being a cartoonish experiment and I really fell in love with these brothers, especially Eli.

"There's still a fair amount of subversion in there, but lovers of the traditional Western tell me they're really enjoying the book."

The subversion comes in the writing - a flat, dryly comic first-person narrative that rejects any flowery descriptions of the wide-skied frontier - and the character of Eli. He's not a hero in the traditional sense of the Western, not least because he's a hitman for the nefarious Commodore, on the trail of an inventive prospector. In tandem with his brother, Eli commits a number of appalling acts. But he is also filled with doubt, neurosis, self-loathing - not afflictions, I suggest, a John Wayne character ever battles with.

"No, the hero of the Western isn't supposed to have weight issues, is he?" deWitt says. "But the strong, silent type isn't my cup of tea. I'm sure people struggled with the same kinds of emotional problems in the 1850s as we do today, but they were never really documented. Once I had that idea, once I knew who Eli was, it made him a much more real person to work on.

"I couldn't wait to get him to San Francisco, for example, because I knew he would be completely, different, almost shy in those big-city surroundings. He's a little bit of a hick, really - and yet this is a hardened killer."

A killer who hates his job and happens across various strange characters on a picaresque, violent, darkly comic journey to redemption. It's fair to say that anyone who loves the Coen Brothers' entertainingly bizarre filmmaking will "get" The Sisters Brothers. But deWitt isn't so calculated as to follow the vagaries of fashion. The follow-up to his well-regarded debut Ablutions began life as a simple writerly experiment featuring two men bickering with each other, the setting only vaguely "Western" in geography. It was a book about the Gold Rush, found for 25 cents (Dh0.92) in a Portland store, which really set the ball rolling.

"I genuinely don't think I would have written The Sisters Brothers if I hadn't seen it," he admits. "There were all these images that were so strange, these miners in filthy clothes, holding a piece of gold the size of a loaf of bread. This brutal time where it was each man for himself, where people were so keen to live because they were surrounded by death. Once I had a place for them to go, then the book had traction. And I had to recognise that, yes, I was writing a Western."

But it is a Western with 21st-century concerns. We can all relate to feeling trapped by our jobs - and the book is at its strongest when Eli is trying to work out exactly why he's followed a life of crime and devilment. For that, deWitt turned to his own life.

"I'm a writer now, but every job I had before dissatisfied me," he remembers. "And this wasn't a minor thing in my life; I genuinely felt resentful. It wasn't so much that they were bad jobs, but being self-educated meant I didn't have a lot of options. So I washed dishes for six years, I worked construction, I painted houses, worked as a clerk at a clothing store. Jobs that weren't mentally demanding of me but drained me and paid poorly.

"Every day I was working was another day I wasn't writing, but to be a novelist seemed like such an unattainable, distant thing. That feeling never left me. To be honest, I was lucky I sold my first book when I did because I was getting dangerously bitter about it. So yes, I can empathise with Eli. In fact, I was surprised by how much I came to care for him."

It's a feeling anyone who reaches the latter phases of The Sisters Brothers will understand, despite the book's huge moral ambiguity. It has much to say on the nature of the sibling relationship, about rivalry and love. In fact, he talks about Eli as if he were his own brother (deWitt is the middle sibling of three) - understanding of his flaws but loving him all the same.

"Seriously, in a writing life, characters like Eli don't come along that often. So you want to do right by them. You want to respect them as if they are real people. I know this sounds odd, but I feel in some strange way that Eli is out there making friends for me. I'm sure he must have got under the skin of the Booker jury, and I'm so happy that he has. It's funny, but I feel thankful to Eli for all of this."

Thanking a fictitious character would be one of the stranger Booker acceptance speeches. Come Tuesday, deWitt might just have to make it.

The Sisters Brothers (Granta) is out now