In Orhan Pamuk's new novel, Suzy Hansen writes, the tiniest details of a Turkish love story accrue into a damning examination of that country's mores and traditions. The Museum of Innocence Orhan Pamuk Faber and Faber Dh114 Orhan Pamuk's Snow, published in 2004, was an appropriate novel for confusing times. A moody, political dispatch starring a western narrator travelling to a mysterious edge-bound Eastern city, the novel explicitly plumbed the theme of clashing cultures, the new fixation of an Islam-obsessed West. Turkey didn't register high or low on the West's enemy list. Yet Pamuk, also prone to postmodern literary games and accessibly rich portrayals of urban life, was seized upon as a friendly native capable of playing cultural translator, all the more so given Turkey's ongoing internal showdown between the secular and the Islamic. The ideas, events and references in Snow are actually difficult to understand without help from a Turkish history book - but no matter. The novel, with its radical Islamists and suicidal headscarf girls, was pounced on as a universal tale for a changed world.

It may then come as a disappointment to Pamuk's new legions of western disciples that his latest novel, The Museum of Innocence, hardly deals with terrorists or violent separatists at all. Pamuk has even stressed this to the press: it's just a love story, the Nobel winner insists - a classic tale of star-crossed lovers, albeit one taken to a curious extreme. Kemal, the suffering hero, ritualistically collects and sometimes steals, objects that belong to his beloved Fusun - her cigarette butts, her ticket stubs, a tricycle. Ultimately, he houses them in a museum erected in her honour. Kemal narrates the novel as a guide to this museum, which we eventually learn is located in a house that once belonged to Fusun's family.

But The Museum of Innocence is far more ambitious than it might first seem; before long, Pamuk spins his love story into a damning social history of Turkish taboos and traditions. For it is in romance, or the lack thereof, that Pamuk locates the twisted source of much of his country's despair. And like Kemal, he seeks to address sadness by preserving its tiniest details - in this case the most personal stories people caught up in Turkey's massive, often bewildering evolution from "Oriental" empire to westernised nation-state.

A Turkish feminist once told me that, "All the problems in this country would be solved if there were only the existence of real romantic love." The idea seemed sentimental, even silly at first. Then the feminist urged me to consider everything from homophobia, domestic violence and honour killings, to women's impoverished rights and arranged marriages: If Turks had the freedom to choose their romantic partners without fear of society's punishment, wouldn't all of these problems ease with time? The feminist knew that romance couldn't eradicate violence. What she wanted me to understand was that, though the Turkish state gave the illusion of embracing western individualism, family and social pressure were brutal, and individual choice negligible. That dynamic, she suggested, was the root of at least some evil.

The feminist was from a wealthy Turkish family, the kind that lives in an old guard, secularist neighbourhood like Nisantasi, where Pamuk grew up and where The Museum of Innocence takes place. Nisantasi sits atop one of Istanbul's many hills, and from this perch, very westernised rich Turkish families have the privilege of reflecting on their nation's lingering backwardness. Pamuk takes that critical eye and turns it on his own people. Today, both the feminist and Pamuk would likely enjoy relative freedom to love as they choose. But 30 years ago, in the era when the novel takes place, members of the Turkish upper class were still juggling their deeply held traditions with the razzle-dazzle onrush of modern life. The Nisantasi elite were Ataturk's liberalising trailblazers - the first to benefit from rapid economic expansion, and to experience the abrupt changes wrought by "modernisation". Kemal, the protagonist of The Museum of Innocence, is born into this most educated class. That doesn't mean he understands the consequences of falling in love with an 18-year-old shopgirl named Fusun.

When the two meet, Kemal is engaged to the aggressively modern, Paris-educated Sibel. Kemal professes to love her, but one gets the sense that he is unfamiliar with loving a woman for reasons other than fine breeding and a pleasing resume. Like every member of her enlightened class, Sibel spends a great deal of time obsessing over the authenticity of foreign handbags and the importance of chic restaurants. Pamuk takes great pleasure in ridiculing such aspirational foolishness. "The Istanbul bourgeoisie had trampled over one another to be he first to own an electric shaver, a can opener, a carving knife, and any number of strange and frightening inventions," he writes, "lacerating their hands and faces as they struggled to learn how to use them."

Just as the rich wound themselves with their coveted western gadgets, they also fumble with their imported social mores. Sex before marriage was once sinful, but Sibel and Kemal are good conformists: "Little by little sophisticated girls from wealthy westernised families who had spent time in Europe were beginning to break this taboo and sleep with their boyfriends before marriage." Fusun does not come from this freewheeling class, but when Kemal recognises her (they are distant relatives) in the shop where she works in Nisantasi, he feels free to manipulate her into bed. They begin to meet regularly at one of Kemal's extra apartments, and these meetings are glorious. We know it cannot end well. One day, Fusun innocently asks whether Kemal and Sibel have also slept together. Not wanting to hurt her, Kemal says that he hasn't, because Sibel isn't as "modern and courageous" as Fusun. Young Fusun is quick to recognise the contradiction of this scenario, in which the less modern woman wins the engagement ring, and the modern woman gets afternoon trysts with no future. "Actually, I'm not modern or courageous!" she cries.

Sibel, meanwhile, believes that she and Kemal are forever bound to one another, precisely because they have slept together. When Kemal's obsession with Fusun becomes gossip, their engagement flounders, and their positions in society plummet. "This episode had served as potent warning to girls of our generation in Istanbul society not to put too much trust in men before marriage," Kemal notes, "and, if the rumours were to be believed, inspired terrified mothers with marriageable daughters to urge extreme caution." The lower-class Fusun, meanwhile, broods in Pamuk's crooked, dark Istanbul backstreets, waiting for Kemal's visits. Later, Kemal reveals that he believes Sibel can recover from her lost virginity better than Fusun, because Sibel is "rich and modern".

At times, Kemal's love for Fusun feels self-serving and predatory, more than romantic, and his lament is sometimes difficult to bear. The ponderousness of several passages, in which we're left swimming for pages in Kemal's repetitive, self-centered preoccupations, effectively distract us from Fusun herself, the great mystery of the novel. What does she want? Do we even wonder? By the novel's final pages, the reader feels reprimanded by Pamuk for proceeding precisely as Kemal has: blissfully ignorant of a woman's desires. While this twist is well-executed and satisfying, Pamuk asks a lot of his readers to put up with the mopey Kemal until the end.

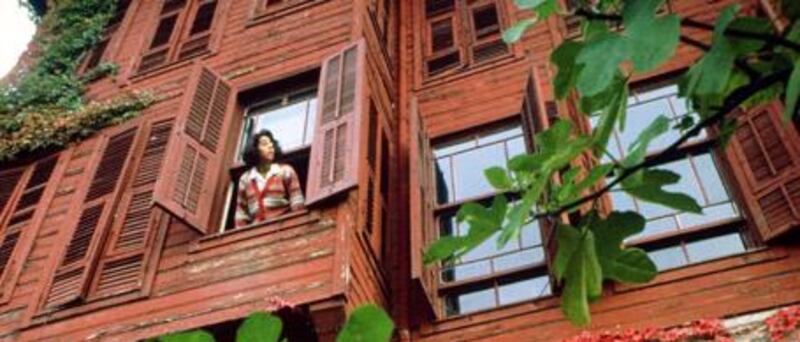

Fortunately, The Museum of Innocence is more than Kemal's musings and hoarding of matchbooks, and readers turned off by Pamuk's narrator will be sustained by Pamuk's Istanbul. Once again, he proves himself a stunning creator of his gloomy, magical city. As in his memoir Istanbul, or his great Istanbul novel The Black Book, we follow Pamuk out of the gleaming avenues of Nisantasi, along the miracle of the Bosphorus, and down through the dirty, mournful, laundry-strung backstreets. In one of the novel's many surprising turns, Fusun decides to become an actress, and Pamuk draws us into the Istanbul film industry, a seedy, cafe society that once gave rise to a golden era of national cinema. "I delayed not a moment in visiting the backstreet haunts, the prospective production offices, and the coffeehouses where second-class actors, would-be film stars, bit players, and set workers played cards," Kemal recalls. It is a world away from Nisantasi - actresses were then usually perceived as whores - and proof of how far Kemal has fallen, at least by his neighbourhood's standards.

But Pamuk is also being playful here. His own melodramatic plot is an explicit reference to these old tales of Turkish Romeos and Juliets. Splicing these old films into the novel's plot helps complicate the cliché of messy, emotional "Eastern" peoples. Yes, Kemal is lovelorn and self-indulgent to the extreme. But when individuals are strangled by poverty, religion, tradition and the state, emotions can be lived large, feelings heightened by all that is prohibited. That which we might call cliché - the standard cinematic arc of a rich boy-poor girl romance, for example - can in fact be terribly moving.

It is left to Kemal's distraught, pushy mother to warn him that he might be the victim of impulses he does not understand - that movie love is just for movies, not for Turkey. "In a country where men and women can't be together socially, where they can't see each other or even have a conversation, there's no such thing as love," she despairs. "Because the moment men see a woman showing some interest, they don't even bother themselves with whether she's good or wicked, beautiful or ugly - they just pounce on her like starving animals. This is simply their conditioning. And then they think they're in love. Can there be such a thing as love in a place like this? Take care! Don't deceive yourself."

Kemal and Fusun barrel toward disaster; only someone with Pamuk's storytelling gifts could leave us unsure of how their tragic romance will end. For a fleeting, hopeful moment, Istanbul, cavernous and shadowy, grants the lovers the right to disappear together. They explore the city in tentative anonymity, far from society's needlelike gaze. "The city was teaching us to see the ordinariness of our lives, teaching us, too, a humility that banished guilt," Kemal says. By this point we know that lovers can remain lost in Istanbul for so long. The expression of genuine human desire seems impossible for those pulled between the demands of religion, the state, and their own families, all three forces jostling for authoritarian supremacy. But in the poor-city innards of his ancient cosmopolis, Pamuk finds a happier, more democratic chaos, a place where lovers can be free, if only for a short while.

Suzy Hansen, a regular contributor to The Review, is a writer living in Istanbul.