Why do writers write? For reasons much like anyone else enters the profession of their choice: for money, for security, for professional advancement, to prove their skill. But writers are also driven to write because, like everyone else, they are lonely, and aching to be heard.

Novelists and authors of literary non-fiction operate within tightly structured, rigorously policed formats, but other forms - the personal essay, the collection of letters - offer the possibility of bypassing what might be seen as the stodgy formality of literature. They tantalise with the promise of direct address to the reader.

Having edited the esteemed The Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate is back now with two new volumes: Portrait Inside My Head, a new collection, and To Show and To Tell, a how-to guide to the crafting of personal essays. Lopate is president of the booster club, his essays about, among other things, the power of the essay to transform. "I persist," he tells us in the introduction to Portrait Inside My Head, "because I know the truth, which is that, deep down, you love essays. You may be ashamed to admit it. But you love essays, you love essays, you are getting very sleepy, you lo-o-ove essays …"

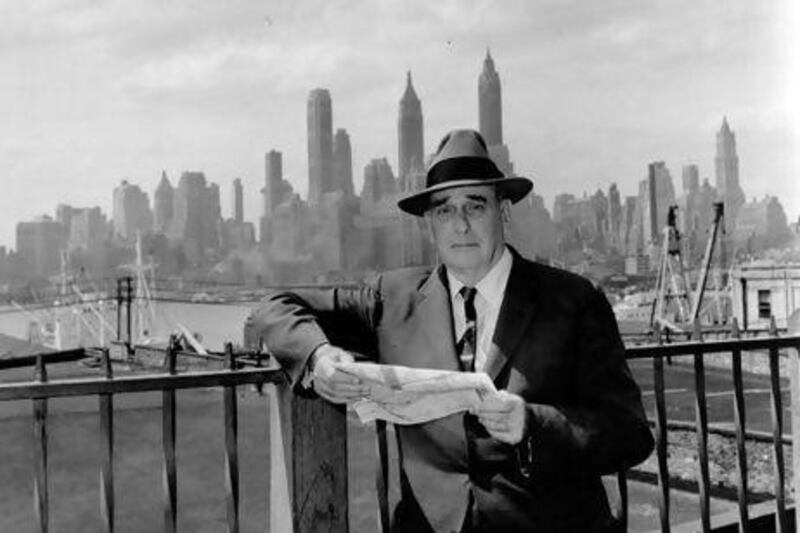

Lopate is a film critic and urban historian in addition to a personal essayist, and Portrait, as its title promises, is a mélange of reflections on his Brooklyn childhood and sibling rivalry with his radio-host brother alongside musings on baseball and the mixed legacy of Robert Moses. Uniting these disparate efforts is Lopate's willingness - his unflinching desire - to uncover the hard truth, even at his own expense. Writing about his friend, the filmmaker Warren Sonbert, who died of an Aids-related condition in 1995, Lopate locates the source of his discomfort with Sonbert's romantic escapades: "I was repelled by that seemingly effortless promiscuity, which mocked the consequential difficulty of life as I understood it."

Lopate visits the Plaza Hotel for tea with his young daughter, and is shocked to find himself amused when she is inconsolable over the loss of a balloon. "I felt myself bonding with my daughter in our now-shared discovery that life was composed, at bottom, of loss, futility, and ineluctable sorrow. There was nothing you could do about it but laugh."

Given Lopate's own mastery, as amply evidenced once more with Portrait, it comes as a surprise that To Show and To Tell is marked by so flat a prose style. Lopate is simultaneously writing for adepts of the essay and for students only beginning their studies, and the disjunction makes for a book intended for everyone and no one in particular. To Show and To Tell is worth a look, though, if only for Lopate's carefully curated list of essay collections and memoirs worth reading, ranging from William Hazlitt to AJ Liebling to Jonathan Lethem.

Lopate is also responding, with a kind of bemused tolerance, to the rhetorical excesses of David Shields, whose Reality Hunger was an extended roar of displeasure at the sclerotic literary establishment, and a brief in favour of ambiguity and playfulness. "An irony of Shields's stimulating if willfully perplexing book," Lopate says of Reality Hunger, "is that he professes to be bored by novels and short stories and to prefer reality, while at the same time insisting that nonfiction is really a fiction, of sorts." Whatever their philosophical differences, Lopate and Shields share a passionate devotion to the personal essay, and a quasi-mystical belief in the act of writing as a hedge against loneliness and death.

Lopate and Shields both are remade by minor epiphanies about the nature of their calling. Lopate, a student activist at Columbia University in the 1960s, is surprised by the sight of a bird, distracting him from his talking points: "I couldn't forget that a part of me was truer to watching the blue jay than to caring about the impact that a new university gymnasium proposed for Morningside Park might or might not have on the adjoining Harlem community."

Lopate finds his calling in the fleeting beauty of the known world, his work as an essayist reflecting his passion for the glorious mundane: "Regardless of the genre I happened to be working in, I found myself resisting the transcendent … the inability to reach the stars, to achieve anything like spiritual sublimity, became a stubborn claim that the earth is all we have - a brief for groundedness."

Shields, similarly stubborn, treats How Literature Saved My Life as a free-form sequel to, and explication of, his 2010 book Reality Hunger. The book had been constructed out of quotes and chunks of text appropriated from other authors, and How Literature similarly reuses pieces of Reality Hunger without attribution.

Like its predecessor, How Literature is enamoured of the autobiographical, the self-referential, the self-absorbed, the ambiguous. "The writer getting in the way of the story is the story, is the best story, is the only story." This is the crux of Shields' own work, and How Literature is, in part, a making-of documentary of Reality Hunger, complete with an epiphany of his own: "I newly knew that the digressions were the book. The seeming digressions were all connected. The book was everything in front of me. The world is everything that is the case."

Shields, like Lopate, writes out of a hunger to connect, and a writer's knowledge that words are never enough: "We are all so afraid. We are all so alone. We all so need from the outside the assurance of our own worthiness to exist." Shields' advice to other writers, pithy and incisive, is the guidebook To Show and To Tell wants to be: "What separates us is not what happens to us. Pretty much the same things happen to most of us: birth, love, bad driver's license photos, death. What separates us is how each of us thinks about what happens to us. That's what I want to hear."

Shields, the inveterate quote-swiper, invokes JM Coetzee on "the mark of great writing". The Nobel laureate Coetzee's sideline from writing novels, for the past few years, has been exchanging letters with fellow literary titan Paul Auster. Coetzee and Auster spend a good portion of Here and Now: Letters 2008-2011 discussing the symbolic import of sports, and the reigning metaphor here comes from baseball; each writer lobs a slow softball over the middle of the plate, leaving it open for the other to smack it out of the park. The all-consuming literary jealousy and rivalry limned by Lopate and Shields is replaced here by a brotherhood forged in the fire of shared struggle. "We have been at it for close to three years now," Auster tells Coetzee, "and in that time you have become what I would call an 'absent other', a kind of adult cousin to the imaginary friends little children invent for themselves."

Winner of two National Book Awards, a Guggenheim fellowship, and countless other prizes, William Gaddis would be, by most definitions, another charmed literary soul. And yet, the missives collected in The Letters of William Gaddis, in both form and content, are run-ons: assemblages of clauses, one after the other, that are also a single, weary cry of frustration at the indignities of writing. These letters, addressed first to his mother, then to his two wives, two children, and a variety of academics and publishing veterans, convey little of Gaddis's intellectual passion, but a great deal about his financial and artistic anxieties. But Gaddis knows this from the outset, and seeks to redirect our attention back to where he believes it best belongs: the novels themselves.

"Our correspondence should never be published," Gaddis writes to his mother in 1949. The passage of time does little to allay his fears that the literary world is more interested in personal detritus than in the books he agonised over. "I think I meant it when Wyatt says that the artist is the shambles of his work," referencing the protagonist of his debut novel The Recognitions, "but here it's those shambles they want to devour." Gaddis requires over a decade to complete his monumental novels The Recognitions and JR. Even Carpenter's Gothic, intended as a brief, sellable amuse-bouche after the enormous undertaking of his first two books, takes another decade.

By the time each novel is completed, Gaddis is exhausted by the process of writing, and thoroughly emptied of his initial passion: "I am so tired of it, have entirely lost interest in every bit of it, and being quite assured that I'm never going to make any more money from it, would so happily forget the entire evidence of wasted youth."

There is little glamour here, although Gaddis does correspond with the likes of Saul Steinberg, Mary McCarthy and Saul Bellow. Instead, threaded through all the complaints about money troubles and romantic difficulties and health crises, there is Gaddis's recurrent question, found both in the work and the life: "What's remained seems to be preoccupation with the Faust legend as pivotal posing the question: what is worth doing?"

Saul Austerlitz is the author of Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy.