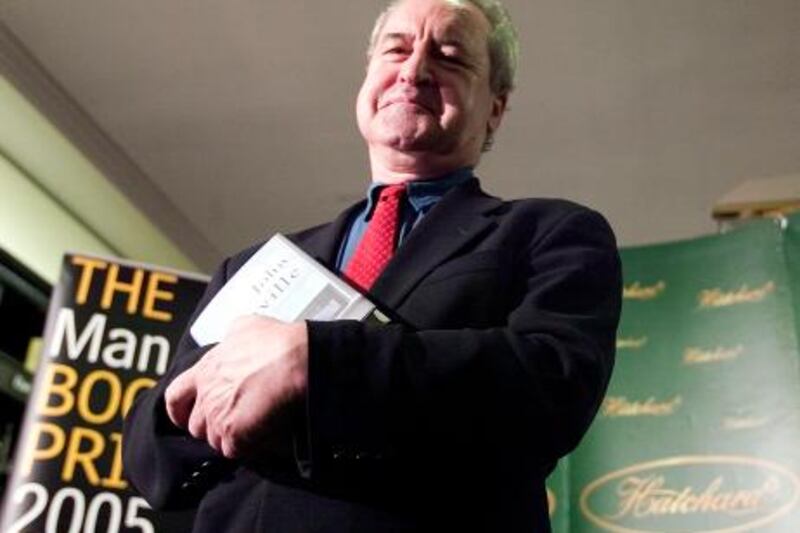

When John Banville was named the surprise recipient of the Man Booker Prize in 2005, he held up a copy of his book The Sea and proclaimed: "It's nice to see a work of art win."

It was a controversial statement intended to bait those who had expected the latest, more mainstream work by Sebastian Barry, Kazuo Ishiguro or Zadie Smith to emerge victorious. Six years on, sitting in Pichet, his favourite restaurant in Dublin, there's still a glimmer in his eye when we talk about his most famous book.

"I meant that, you know," he winks. "I knew people were annoyed that I'd won in a year where there were plenty of popular, middlebrow novels. They also didn't like that I said I hate my novels - and I will concede that I've made the mistake of not qualifying that statement. They're better than anyone else's ... they're just not good enough for me."

Spend any time with Banville, and it's clear that he's not so much arrogant as mischievous. The 65-year-old had, until The Sea, always been admired for his poetic, almost painterly prose, but his work came with a caveat - that it was wilfully difficult and complex. He had been shortlisted for the Booker before, for 1989's The Book of Evidence, but readers didn't turn to Banville for light relief. Because every sentence felt pored over, it's inevitable that looking back at these novels is, for Banville, rather painful.

So it was quite a surprise - and perhaps a piece of mischief-making in itself - that, instead of sitting down after his Booker triumph to finish off the novel that would become 2009's The Infinities, Banville decamped to Tuscany and, as he remembers now, "discovered I could write crime fiction". Instead of tormenting himself with the possibilities of language, he found a childlike enjoyment in making up stories. "People presumed I have a chart on the wall with all the people in the book, where the murderer is, and so on," he laughs. "But no, I just made it up! I was half way through the latest book before I knew who the killer was.

"In fact," he whispers conspiratorially, "I rather suspect it doesn't matter who it was."

Five crime novels featuring the escapades of pathologist Quirke have tumbled from Banville's pen in quick succession. The latest, A Death in Summer, is great fun - both convincing in its period 1950s Dublin detail and a genuinely gripping murder hunt. Although, to say it's from Banville is slightly inaccurate; for these thrillers he writes under the pseudonym Benjamin Black.

"I chose a different name because I was really keen to make sure people realised this wasn't some sort of elaborate postmodern joke," he says.

I tell him that's what I feared - irony-laden books from a "literary" writer taking the mickey out of the conventions of crime fiction.

"Oh no, I respect the genre too much for that," he says. "More than respect, actually, I love crime fiction. I don't feel bound by the conventions, either - I love working with them. Stravinksy once said that freedom is found within the rules, and it's true. I'd like to go back to when the writer was an artisan - my perfect job would have been to be one of those writers somewhere in Hollywood, churning movies out in the 1950s, cigar stub in hand. Somebody saying to me, 'we need two scenes by 4pm, and they'd better be funny, kid, or you're off the picture'."

Banville's career is dotted with film and television work. He wrote the screenplays for Elizabeth Bowen's novel The Last September (a Deborah Warner film from 1999, which he admits didn't quite work) and the forthcoming Albert Nobbs, based on a George Moore story and set in Dublin during the 1890s. "If they do it right, it will be superb," he promises of a film starring Glenn Close and Jonathan Rhys Meyers. "But moviemaking is a volatile, peculiar thing."

The Sea is also in development and the BBC is currently planning a three-part Quirke series - ironic, since the bare bones of the first Quirke novel came from a Banville screenplay that never got made. "I know, it's gone full circle," he smiles.

"I love the pace of working in films," he adds. "When someone rings up and says: 'We need a couple more lines of dialogue', and you have to fire them off... I love that." Which, in a way, is how the Benjamin Black novels have been approached. It genuinely amuses Banville that he has written five in five years - to the extent that he's taken to talking about his two writerly alter egos in the third person. "It's like the tortoise and the hare," he laughs. "Banville will still be sharpening his pencil when Black is polishing the final chapter."

But, despite revealing over our lunch that the Black books are "without style", they do still bear some of Banville's hallmarks. The beautifully crafted descriptions - "his entire forehead crinkled, horizontally, like a venetian blind being shut" - are still there.

"There are plenty of crossovers, really," he says. "You know, all fiction is about secrets. In so-called 'literary' fiction you uncover the meaning behind things that are in plain view. In crime fiction, well, it's obvious that the whole form operates because of secrets.

"But to be honest, I hate these distinctions, these categories. Don't you think it's bizarre the way everything is categorised? I was in this bookshop in Chicago recently, a small place in the train station. There was 'new fiction', 'paperback fiction', 'fiction' and then 'literature', which had Joseph Conrad, Henry James and so on. But nobody is going to go to that section are they? I felt like saying to the owner 'will you please just take those books and put them in fiction?' Stop this nonsense!'"

Where might Banville's work end up in the future if, indeed, bookshops still exist? When Rick Gekoski was reviewing The Sea in The Times, he bet that "it will still be read and admired in 75 years". It may well become a modern classic - in fact, it's such a piercingly beautiful meditation on love and loss that it's given Banville a problem. People think he can solve their issues.

"Yes, it's interesting," he says, with the same sense of bafflement as many of his male characters. "I have a friend who is in a constant state of emotional chaos. She rang me up once and said: 'John, what am I to do?' And I said: 'Why are you asking me? I don't know.' And she replied: 'Because you're a novelist'. She couldn't see that she was asking exactly the wrong person. I can write about life - that doesn't mean I know about it. She couldn't understand that my work is all about my imagination."

And his Benjamin Black alter ego has fired that imagination in ways he - and, to be honest, his readership - could never have believed. The books are as good fun to read as they clearly are to write. How many more will he do?

"Well, my real ambition is to write a crime novel without a crime in it, featuring someone who thinks a crime has been committed but actually it hasn't. The story could get more and more vague rather than clearer and clearer."

There's that mischievous side again. That's not really sticking to the genre conventions you claim to enjoy working with, is it?

"Er, no. So maybe John Banville and Benjamin Black will have to do a collaboration one day. Writing as 'John Black', maybe. How does that sound?"

It sounds great.