On April 27, 2011, a panel of distinguished experts gathered at the Manarat Al Saadiyat in Abu Dhabi for a public discussion about the role of national museums in shaping a nation’s identity.

The focus of their discussion was the emirate’s nascent Zayed National Museum, but at one point the panel found itself treading on the fragile eggshells of the Middle East’s tumultuous past.

It came as no surprise, given the composition of the panel.

On one side sat Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum, with Henri Loyrette, who in 2011 was the director of the Louvre in Paris. On the other, Shobita Punja, the head of the Indian government’s National Culture Fund, with Wafaa El Saddik, a former director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Here were the winners and losers of the imperial age of museum making – and it didn’t take long for the “P” word to crop up.

After listening to MacGregor and Loyrette extolling the virtues of their national museums as depositories of world history, Saddik reminded the audience how the British Museum and the Louvre had come by that status.

“In the 19th century, Egypt was plundered,” she said. “Everybody who came to Egypt took what he could.” MacGregor and Loyrette had the grace to look a little sheepish. “Even obelisks,” Saddik added, in a clear reference to the two so-called Cleopatra’s Needles that adorn Paris’s Place de la Concorde and the Victoria Embankment of the Thames in London.

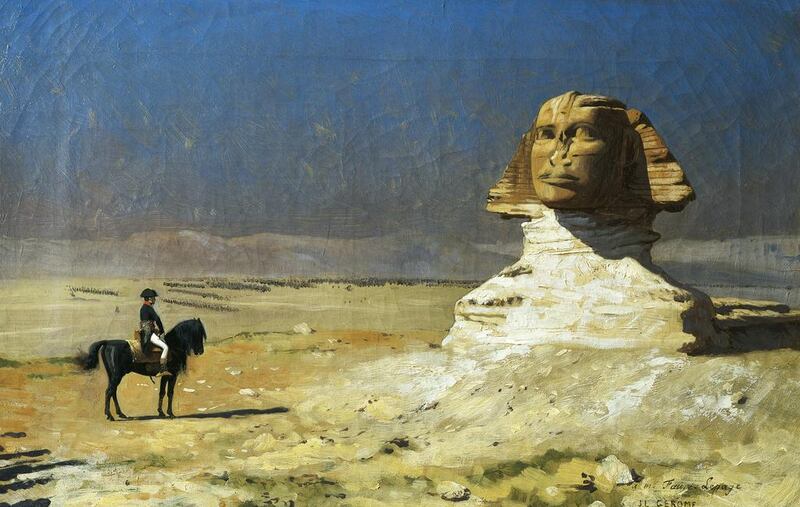

One of the first Europeans to come to Egypt with the intention of helping himself to its treasures was Napoleon Bonaparte, the subject of a new and detailed biography by Michael Broers, professor of western European history at Oxford University, which makes clear the pioneering role played by the ambitious tyrant in the ensuing systematic cultural rape of the land of the pharaohs.

And Loyrette, sitting alongside Wafaa El Saddik on that warm spring evening three years ago in Abu Dhabi, was a living reminder that the moulds of imperial relationships cast in history are not easily broken.

Loyrette was the direct corporate descendant of Dominique Vivant, the first director of the Louvre – and, as Broers’ biography reminds us, Napoleon’s looter-in-chief in Egypt.

At the tail end of the 18th century, Egypt found itself playing the role of collateral victim in the imperialist struggle for power being acted out between France and Britain. Realising that Britain’s navy rendered it immune to invasion, the French decided the best way to cripple perfidious Albion was to disrupt its dependence on India’s wealth – and if Egypt fell, they reasoned, India would follow.

It was a half-baked plan, doomed to ultimate tactical failure, but it appealed to the ambitious Napoleon. Already dreaming of world domination and barely a year from executing the coup d’état that would see him installed as ruler in the dangerous political swamp that was post-revolutionary France, he nevertheless took care to disguise personal ambition as national interest.

“The vast Ottoman empire, which is crumbling every day, obliges us to begin thinking very soon about how to preserve our commercial interests in the Levant,” he wrote to his superiors in August 1797. Fresh from enforcing French dominion over Italy, he got the job.

The most curious aspect of the 36,000-strong invasion force that Napoleon assembled at Toulon the following year was its smallest unit: the 167-strong Commission des Sciences et des Arts, headed by the classic 18th-century polymath Dominique Vivant – diplomat, writer, artist and archaeologist.

Napoleon, writes Broers, had “rallied the troops with promises of untold plunder” and in the commission, a body organised along strict military lines, he had assembled a force whose objective was opposite that of the Allied unit whose exploits at the end of the Second World War are celebrated in the film The Monuments Men.

When the French hit the beach at Alexandria on July 1, 1798, with them went Vivant and his “unique, seemingly incongruous … team of intellectuals, academics and artists, assembled at Napoleon’s own behest, with the dual purpose of studying Egypt, ancient and contemporary, and of disseminating French civilisation there”.

Since wars began, armies have always looted. But this was the first time that the commander of an invading force had set out with the rape of an alien culture as one of his key tactical objectives.

In Egypt, the French found themselves facing a landscape and climate “alien and … forbidding”. Alexandria fell easily but “only after the French had had their first battle – with the scorching heat, a lack of water and burning sands”.

Next came the march to Cairo – “sheer hell” – rewarded by overwhelming success at the Battle of the Pyramids. Against the spectacular backdrops of the pyramids of Giza and the minaret-studded skyline of Cairo, the French formed squares and, unleashing a hail of perfectly orchestrated musket and artillery fire, efficiently picked off the Mameluke cavalry that swirled helplessly between them.

It was an unfair contest between arms ancient and modern, and it lasted just two hours. The Egyptians lost 2,000 men, the French fewer than 30.

Telling the locals he had “come to liberate them, to restore the fairness and equity of true Islamic law, and also to imbue them with the liberty of his own revolution”, Napoleon set about doing what he did best – imposing a ruthless, bloody dictatorship. Vivant and the other proto-Monuments Men, meanwhile, set about filling their crates. After a brief but bloody excursion into Palestine and Syria, Napoleon grew tired of Egypt. On August 22, 1799, a little more than a year after landing, he slipped away back to France and his destiny, leaving his army to endure British naval blockades and Bedouin guerrillas until its eviction in 1801.

Back in Paris, Napoleon rewarded Vivant – soon to be created Baron Denon – by appointing him as the first director of the Louvre, the one-time royal palace that had become a public museum.

Today, thanks to Vivant and the Commission des Sciences et des Arts, the Louvre remains home to one of the largest departments of Egyptian antiquities in the world, holding objects dating from the 12th century BC to the 4th century AD.

Does the world need another biography of Napoleon? After all, his wider story is better than well known – ever since Sir Walter Scott’s biography, published just five years after the Emperor’s death in exile on St Helena in 1821, there has never been a shortage of books about the man.

But this latest contribution to the canon is the first to make use of the definitive collection of Napoleon’s correspondence, painstakingly assembled from myriad sources and brought together in chronological order for the first time by the Napoleon Foundation in Paris – an ongoing labour of love that, at the time of publication, had extended to nine volumes and the year 1809.

Its importance is that it replaces as the key source for historians the heavily doctored and hagiographic edition of Napoleon’s correspondence produced by his nephew, Napoleon III, between 1858 and 1869, and which until now has allowed only a rose-tinted view of Old Boney. As Broers writes: “If the present work has any intrinsic merit, it stems from having put this unparalleled resource to quick use.”

This does not mean that Napoleon speaks directly for himself throughout – this is no mere worthy compilation of wordy quotes – but access to the uncensored correspondence has allowed the author to paint a picture of the flawed man, rather than the omnipotent myth.

In the words of Patrice Gueniffey, editor of the ninth volume of letters, an annotated collection of 3,265 documents from 1809, “the figure of Napoleon the man appears behind that of the emperor, by digression of a sentence, or a remark, an angry word, a sense of passing emotion”.

Here, in contrast to the superman perceived by the writer Goethe in 1836 – “great, because he was always constant” – the letters reveal “a portrait of Napoleon quite different from that which we readily paint today, [a] Napoleon who would have been nothing … without his ministers and his councillors of state, a Napoleon gnawed by doubt – in short, human, very human perhaps, by our standards”.

Human, of course, is not synonymous with humane, as the Egyptians who found themselves under the bloodily imposed French yoke in 1798 might have attested.

Jonathan Gornall is a regular contributor to The National.

[ review@thenational.ae ]