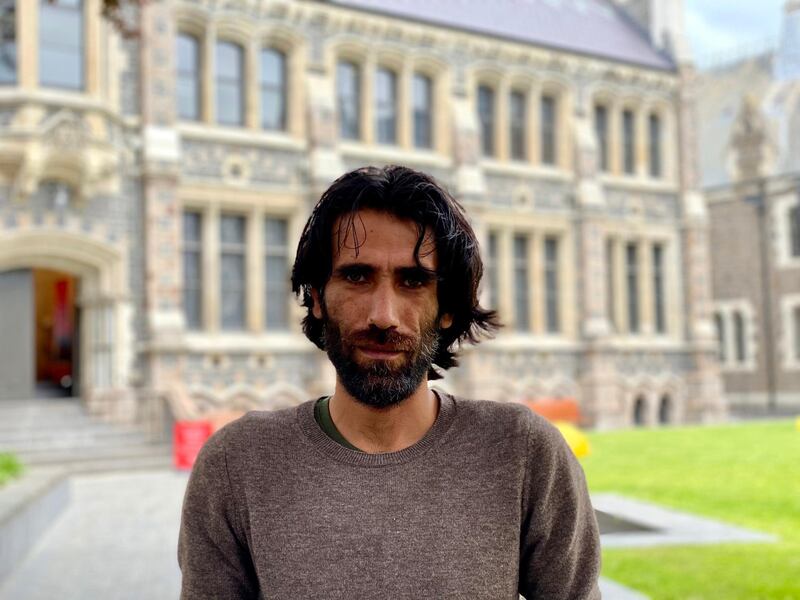

Six years after first being imprisoned on Manus Island for fleeing his home country in search of asylum in Australia, Iranian-Kurdish refugee Behrouz Boochani is free.

Better yet, he is free in the country that has for six years offered to resettle refugees incarcerated in the offshore processing islands of Manus and Nauru; an offer that was consistently rejected by the Australian government.

Boochani has arrived in Christchurch, New Zealand, as a guest of the city's Word Christchurch festival. It is the first time he has left detainment in Australia's offshore processing centres (first, living on Manus, and this year being transferred to the Papua New Guinea capital of Port Moresby).

The journalist, novelist and filmmaker is in the South Island city to speak about No Friend but the Mountains, on Friday. The book was composed via text message from Manus to his friend Omid Tofighian, who translated the work into English from Farsi.

The book recounts Boochani’s journey from Indonesia to Australia by boat, and his ensuing imprisonment by the Australian government, which until his departure, repeatedly refused him entry. Incredibly, it’s been a resounding success in the very country it criticises over its 400-odd pages – picking up A$125,000 (Dh312,000) at the country’s richest literary prize, the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, among several other prestigious awards.

Boochani fled Iran and its oppressive regime in 2013. His boat came ashore at Christmas Island, off the coast of Australia, on his birthday, four days after a new agreement was signed with Papua New Guinea ruling that those found in Australian waters would be taken to a detention centre on Manus Island for processing. It meant, despite months of travelling, he would never be resettled in Australia.

New Zealand has had a long standing offer to resettle 150 refugees a year from Manus and Nauru, but the offer has been repeatedly declined by the Australian government. So it's an interesting place for Boochani to now find himself in, he admits over the phone from Christchurch.

"It was the right time to leave Port Moresby," he says. "Honestly I didn't expect them to give me a visa, it was unbelievable for me."

Boochani first applied for his travel documents nine months ago, relying on help from his lawyer, UNHCR and Amnesty International. He had tried to apply for visas and travel documents in the past, for the many literary festivals and events he has been invited to over the years, but attempts had until now borne no fruit. In 2017, Boochani publicly campaigned and pleaded to be allowed to attend the London Film Festival, for which his film Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time, was shortlisted. The film was shot on a smart phone from within Manus. Despite writing to London mayor Sadiq Khan and appealing to the Australian ambassador to the UK, no visa was forthcoming. "For the other events [I was invited to], I didn't apply because I knew I wouldn't be allowed to go," he says.

He is now in New Zealand on a one-month visitor’s visa, and is keen to extend it, if he is able to. And, for now at least, it seems New Zealand writ large is willing and ready to help him. He arrived in Christchurch on November 15 to a civic reception and a traditional Maori mihi whakatau – a formal welcome.

He was greeted from the plane by Lianne Dalziel, mayor of Christchurch, as well as the city's Maori leaders, and NZ Greens party MP Golriz Ghahraman, herself a former Kurdish refugee from Iran.

“The people are so welcoming. I’m so busy meeting with the community,” he says. “It’s very nice. The mountains here, they are very similar to the ones in Kurdistan. The people are very good, too.”

Boochani spoke speaks fondly of the most recent sightseeing trip he was taken on by community members; a day at Castle Hill, or “this special place with many rocks”, on Wednesday.

Such a rediclilius and unacceptable statement by Labor Party. You exiled me to Manus and you have supported this exile policy for years. I don't need you to welcome resttlement for me in a third country. https://t.co/XHIBCcrUQY

— Behrouz Boochani (@BehrouzBoochani) November 15, 2019

Understandably, the question on everyone's lips is whether he'd like to stay in the country on a more permanent basis. Several articles in the New Zealand media have openly campaigned for him to stay, or at least, for the New Zealand government to support a bid for asylum. Iranian-Kiwi writer Donna Miles-Mojab, a patron of Word Christchurch and one of the people who sponsored Boochani's trip to New Zealand, wrote an article for Stuff, stating: "We should beg him to stay and hope that he would accept.

“By allowing Boochani to stay, New Zealand would add to the intellectual and literary freedom of its own citizens who, at times, because of New Zealand’s geographical isolation, miss out on the richness of diverse minds and ideas that come together so easily and so often in other parts of the world.”

However, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has openly told New Zealand media that any bid for permanent resettlement would be an independent statutory process, and he would not be given special treatment. But Boochani isn’t willing to commit to anything just yet. “I love this country. But I’m not in a position to say that I want to live here, I am a refugee.”

When The National spoke to Boochani last month, he was applying for resettlement in the US.

He wouldn't be drawn on whether he was still pursuing that option, and admitted he didn't know where he would go once his New Zealand visa was up. For the time being, he would prefer to focus on the literature. He stresses that he is in New Zealand as a writer first and foremost, and wants to focus on the coming days before he thinks about his long-term future. He hopes his appearance at Word Christchurch will draw attention to his book, rather than his political standing, but acknowledges that "people have a lot of questions". He says he would not stop campaigning for the 250 refugees left in Port Moresby awaiting repatriation.

“For now the important thing is that I’m free and people here are welcoming me as a writer and as a person.”