Ask your average anglophone reader to name an Azerbaijani writer and there is a good chance they will draw a blank. Kurban Said doesn't count because the name that adorns the jacket of Ali and Nino, the spellbinding romance commonly regarded as Azerbaijan's national novel, is a pseudonym. Some claim the true identity of the author might even have been an Austrian baroness.

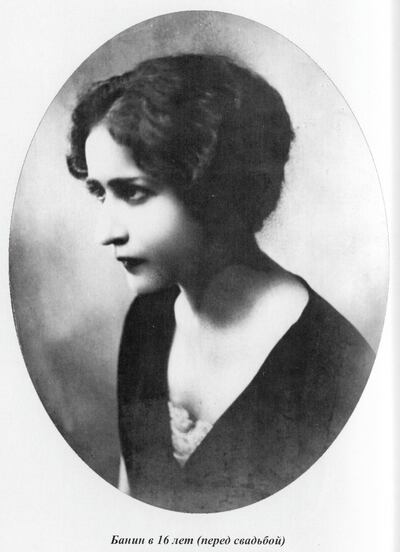

If there's any justice, then the first English publication of Days in the Caucasus will raise the profile of a bona fide Azerbaijani author who went by the name of Banine. This book, a captivating memoir of her childhood and early teenage years in her home country, was originally published in French in 1945. Anne Thompson-Ahmadova's seamless translation into English introduces us to a unique narrative voice and immerses us in an opulent world that has since vanished.

Banine's real name was Ummulbanu Asadullayeva. She was born in 1905, a year she describes as "full of strikes, pogroms, massacres and other displays of human genius". Maintaining this sardonic tone, she claims to have added to the chaos and bloodshed "since I killed my mother as I came into the world". She grew up in a family that had become incredibly wealthy through the discovery and sale of oil, but as her father was often away on business, Banine and her siblings were frequently left in the care of a German governess.

The whole family would spend half the year in Baku and in spring, before the city became dusty and stifling. The family, their relatives and an entourage of domestic staff – "the population of a small village" – retreated to a country estate. Banine recalls long days of hammam parties, storytelling, trips to the Caspian Sea – and playing at "killing Armenians" with her boisterous cousins, Asad and Ali.

Now and again, clouds gather over the family. There is a protracted fiery feud over a grandfather's inheritance. Banine's pangs of young love ("this celebrated malaise") for a family gardener, a Georgian prince and an officer result in disappointment. Her eldest sister Leyla elopes with a suitor, which the family refers to as "the Great Shame" and they discuss it "in the same way they talked of an earthquake or a great plague". Her father remarries, but his glamorous, cosmopolitan wife detests backwater Baku and is indifferent towards Banine.

Soon enough, Banine's life is engulfed by more turbulence. The Russian Revolution erupts and she is cooped up indoors for two weeks while violence breaks out on the streets. Peace is restored briefly and Azerbaijan declares independence from Russia, but soon the Red Army rolls into town and reclaims the errant country.

The second half of the book comprises a dramatic change in fortunes. With the Russian Empire now solidly Soviet, the family is stripped of their wealth. Some members flee to France, but Banine's father is jailed. The Baku house is deemed too large for Banine's family and a commissar, his wife and their staff move in; the country house is similarly carved up, its rooms requisitioned for a holiday camp for revolutionary veterans.

Two remarkable events end this phase of Banine's life, paving the way for a new start. At 15, she marries Jamil, a man 20 years older than her. She loathes him. In 1924, she finds a means of escaping both her husband and her homeland. In Constantinople, Banine bids him farewell and boards the Orient Express, which is bound for the city of her dreams, Paris.

Days in the Caucasus is an unalloyed delight. As a narrator, Banine is appealingly candid and refreshingly self-effacing, quick to mock her "odd, rich, exotic" family, her benighted compatriots, and her own appearance, sentiments and allegiances. Many of her recollections are presented as wry observations, such as "our meals were poor in provender but rich in sighs and tears". Other moments are also funny, not least when some relatives are searched by militiamen in a botched bid for freedom. "There were jewels in my aunt's hair, in the children's mouths, in the hems of their clothing."

Other than Banine, two characters light up the page: her eccentric uncle, who offers philosophical wisdom and pilfers ashtrays and cutlery from hotels, and her formidable grandmother, an "excessively fanatical" Muslim with a foul mouth and penchant for poker.

This is a vivid coming-of-age story that also provides a valuable glimpse of a life lived in a half-Islamic, half-western world at a pivotal moment in history. Banine wrote a sequel called Days in Paris. If there is as much wit, charm and insight in that book as there is in this one, we can only hope it will also be translated into English soon.