“The mark of a good book is that any reader should be able to pick it up and experience the story being told,” says 2022 Booker Prize winner Shehan Karunatilaka, in between global book tours and working on his next “much lighter” novel.

“I never intended – nor aspired – to direct my writing towards an international audience,” he says, in regard to his debut novel Chinaman and his acclaimed The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, which was first published as Chats With The Dead. “The goal was always first to get published at all – and probably make its way to the rest of South Asia.”

Contemporary Sri Lankan stories in the wider literary space have historically been few and far between, although there’s been a silent battle for recognition raging from behind the scenes over the past decade. Karunatilaka is the second Sri Lankan to win the Booker Prize, after Sri Lankan-Canadian Michael Ondaatje in 1992. Previously, Romesh Gunesekera made the shortlist in 1994, followed by Anuk Arudpragasam in 2021.

Although the anglophone South Asian contemporary fiction and semi-fiction genres have been traditionally dominated by Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani writers, such as Aravind Adiga, Arundhati Roy and Mohsin Hamid, Sri Lankan authors are now forging ahead in the international literary arena as equally compelling voices from the Global South.

Excluded from what’s come to be known as “partition literature” common to all these countries, Sri Lanka has its own deeply devastating stories of displacement, colonialism and conflict to tell.

Since the end of the Sri Lankan civil war, adult literary fiction centred on the events has noticeably been the prevailing genre and subject of choice for both Sri Lankan diasporic and non-diasporic voices from either side of the divide. Many will remember Anil’s Ghost (2000) by Ondaatje and Nayomi Munaweera’s Island of a Thousand Mirrors (2012). However, in the past five years alone, readers and publishers have been given more reasons to sit up and take note.

Sugi Ganeshananthan’s sophomore novel, Brotherless Night, for instance – released in January and chosen for the month’s cover of The New York Times's Book Review – employs hyperrealism in fiction to provide a painful perspective from within the oft-underrepresented Northern civilian community at the heart of the war.

“There are certain aspects about publishing that make it seem like there can be only one Sri Lankan story when there are endless others,” Ganeshananthan tells The National. “I hope my book takes people to the many other Sri Lankan writers and the stories they choose to tell.”

One such story, recently told by Sydney-based author Shankari Chandran, took home the Miles Franklin Literary Award – Australia’s biggest literary prize. Like Ganeshananthan, Chandran's parents were from a generation of Sri Lankan Tamils who emigrated from the country in the 1970s and 1980s. Chandran addresses themes of identity, race and the trauma of war through her multi-generational novel Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens.

While both Ganeshananthan and Chandran serve up diasporic voices in relaying a shared history, Arudpragasam in A Passage North writes from within Sri Lanka, taking readers on a journey through the war’s immediate wake as he speaks meditatively of displacement, bereavement and even survivor’s guilt.

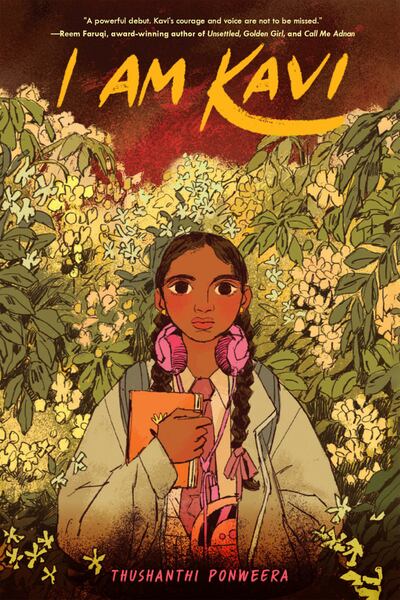

Meanwhile, Thushanthi Ponweera's I Am Kavi, published last month, employs imagery-driven lyricism for her middle-grade novel to tell the story of a young protagonist trying to live an ordinary life in extraordinary circumstances. “My book is not necessarily about the war, but I wanted to write about what it was like growing up around that time – even if to offer just a glimpse into this significant portion of our postcolonial history,” Ponweera says.

While Sri Lankan English language literature is far from a recent phenomenon, this recent “surge” is hard to ignore – with authors now taking ownership of their tremendously rich storytelling heritage beyond just narratives of war and across the borders of various genre and age groups.

“Even though in Seven Moons I too use the civil war as the setting of the book, we have much more subject matter than just the war to talk about,” says Karunatilaka. “It’s nice to see the full breadth of our stories increasingly carving out the space they deserve – to both be told and also be readily listened to.”

Nizrana Farook, who now lives in the UK, is just celebrating the conclusion of her Serendib series: Four books, all replete with daring young protagonists, bumbling baddies and adrenalin-fuelled adventures, but each set in different locations within the semi-fictional isle.

Through her stories, Farook hopes to shares the beauty of the country she once called home, lamenting the lack of Sri Lankan stories on children’s shelves. “With the diversity that Sri Lanka’s history, wildlife and landscapes have to offer, there has always been so much possibility, and the reception has been fantastic.” In addition to raking up awards, her books have also been translated into several languages, making for a wider readership.

Horror writer Amanda Jayatissa, in quite stark contrast, uses Sri Lanka as a backdrop for the adult psychological thrillers for which she has received awards. Taking inspiration from Sri Lankan folklore to relay her love for “disturbing books with shocking plot twists,” Jayatissa’s first novel My Sweet Girl was named Best Debut Novel at the International Thriller Writers Awards in 2022.

She has since published You’re Invited, with her third (Island Witch) set for release early next year. “Literary fiction has always been the common thread between most Sri Lankan English writing, but I decided to explore something more voicey and contemporary that ties back to the culture and experiences I grew up with,” explains Jayatissa who has now moved back to the island following stints in the US and UK.

In a similar vein, Vajra Chandrasekera – writing from Colombo – says he drew heavily from Sri Lankan and South Asian culture, history and mythology for the writing of his fantasy sci-fi debut The Saint of Bright Doors. Published in July, The Wall Street Journal and The New Scientist have already made their endorsements clear.

One is also never too young it seems to embark on an exploration of one’s heritage. Shyala Smith speaks to a much younger audience with her just-published picture book Sai’s Magic Silk – a vibrant adventure story suited for ages three and above.

Some would argue the past few years have presented a “literary renaissance” of sorts for Sri Lankan writing. Either way the stage has been primed for those next in line. “It’s such tough business getting published on an international level that within our community we’ve all been so supportive as opposed to competitive,” says Jayatissa. “A win for one of us is a win for all of us.”

Ganeshananthan agrees wholeheartedly, but also feels that this quantitative occupancy of the space is an opportunity for more qualitative attention. “While I think it’s exciting that there is greater and more diverse representation, I do think that as writers of colour in an international space it is easy for people to focus on the material to the exclusion of discussing the style,” she says.

“As there are more of us out there – and I hope that the numbers and diversity of our stories only multiplies – I would like to see the quality of critical attention paid to marginalised authors also go up.”