Half a dozen teenagers rattling spray paint cans and adjusting ventilation masks stand before a large blank canvas at a cultural centre in Bethlehem. The youngsters are part of a posse of graffiti artists whose work can be found on the stone facades across the West Bank town. Today, however, the group has not come to break any laws. They have been invited to paint a mural to inaugurate the opening of Gaza Graffiti, a photo exhibition currently travelling the West Bank that will soon make its way to nine other towns across Palestine, and later to Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon.

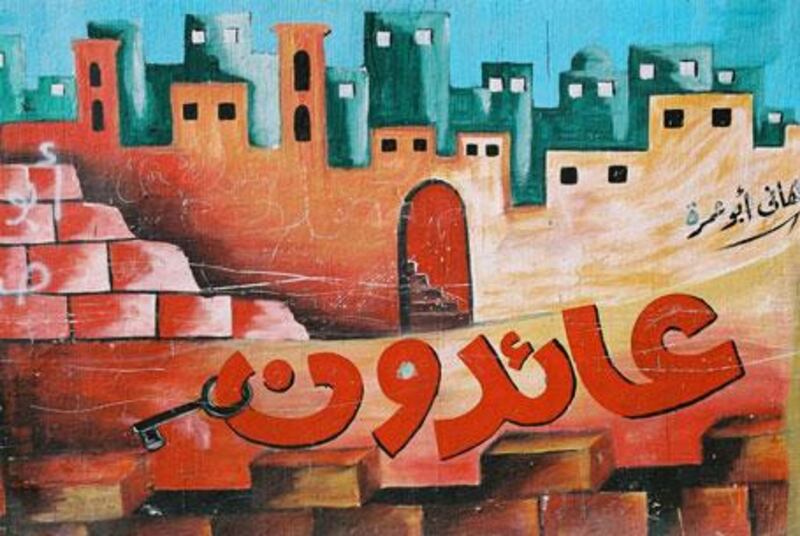

The exhibition features 60 vivid, colourful photographs taken by Mia Grondahl, a veteran Swedish photojournalist who has covered the Middle East for almost three decades. Her photographs explore the fascinating and complex world of Gaza's graffiti, both as impressive art and as the voice of a people under occupation. The photographs, too, are artistic pieces in themselves. Grondahl balances the business of documenting the graffiti's elaborate Arabic calligraphy with a compassionate insight into the artists and communities that produce it.

Graffiti is a serious matter in Gaza. So serious, in fact, that Hamas provides night classes for the artists to improve their technique. The phenomenon's roots go back to times when Israeli soldiers patrolled Gaza's streets before the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. All media of mass communication - newspapers, television, radio - were strictly controlled by Israeli military censors. Political parties countered this by developing alternative media, including graffiti, to get their messages out. Teams of graffiti artists risked their lives to sneak out at night and write slogans on the most prominent walls of Gaza's towns and refugee camps. While at one level the graffiti commemorated deaths or announced strike days in protest at the occupation, it was also a way for the resistance to challenge the hegemony of the occupation.

After the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in Gaza in 1994, the Israeli army withdrew from most Palestinian populated centres, which allowed graffiti artists to work more openly. The result was better art, but probably less relevant politically. The authority had set up its own media networks and used those to promote its policy of negotiations with Israel. Graffiti nonetheless had become such a part of Gaza's media landscape that it mutated into a means of addressing internal Palestinian political debates. Hamas and other groups opposed to the Oslo peace process, for example, used graffiti to undermine support for the authority's policies, particularly its joint security co-operation with Israel.

When negotiations with Israel eventually collapsed and the second Palestinian intifada, or uprising, broke out in late 2000, graffiti re-emerged on the front lines of the new struggle. This confrontation, however, was far more militaristic in nature than the rock-throwing demonstrations between Palestinian youth and Israeli soldiers of the first intifada (1987-1992). The steady stream of Palestinian deaths and the enraged public sentiment provided ample material for artists to translate into slogans of defiance and elaborate murals of resistance.

It was during this time that Grondahl began to pay closer attention to Gaza's graffiti and to document it for the purpose of writing what would later become Gaza Graffiti: Messages of Love and Politics, a medium-sized photography book published by the American University of Cairo Press at the end of 2009. In addition to Grondahl's images, the book also contains investigative essays on the different kinds of graffiti (murals, portraits, calligraphy, congratulations) in Gaza, and their political and social significance.

"Graffiti has always been a barometer of the political situation in Gaza," writes Grondahl. Unlike in western countries where "tagging" tends to be a distinct expression of the artist's individuality, graffiti in Gaza impressed Grondahl for its sense of accountability to a community and its broader ideals and dreams. "It's strongly connected as a real part of the resistance movement," notes Grondahl. "It shows that 'we are unified, we stay together, we want to survive, we are fighting back'. I think graffiti has that unifying sense about it."

Not all of Gaza's graffiti, however, are about angry or defiant politics. A chapter of her book and part of the exhibition are dedicated to the graffiti of celebrations, such as a wedding or the return of community members from the Haj. Kissing lovebirds, big red hearts or floral bouquets brighten the drab, congested alleys of Gaza's cramped residential districts. They are as much a part of the graffiti culture as the three-metre-high faces of the fallen on Gaza's central throughways, or the 10m-long calligraphic script boasting of the accomplishments of the political factions' armed wings.

For Grondahl, this demonstrates how "Gaza's graffiti is so integrated into the society. You're not out there tagging just for yourself. You are tagging for the party you belong to, the block you belong to, for a friend who is getting married, or a friend who was killed. It's an expression of the whole range covering life to death." The ability of Grondahl's work to explore her subject matter unpatronisingly gains heightened relevance in the context of the Gaza Strip's almost complete isolation from the outside world. Israel has incrementally increased restrictions on movement of people and goods into and out of Gaza since the early 1990s, ultimately completely besieging the territory after Hamas came to full power there in mid-2007. In this regard, her work helps viewers explore a world that they have little if any access to - a lack of exposure that time and again contributes to misrepresentations and misunderstandings of Gaza and its people.

Palestinians in the West Bank can equally appreciate these questions of access because for almost 20 years they, too, have been cut off from Gaza. Ayed Arafa, 26, a muralist from Deheishe refugee camp in Bethlehem, says he visited the exhibition out of a desire to understand the Gaza graffiti scene better and compare it with the one he is deeply involved with today in Bethlehem. "We don't get a chance to go to Gaza to meet their artists and to work on projects together, so this was an opportunity to connect somehow," he says.

"Their work is different because their situation is different, though we both suffer from the same occupation. Their graffiti pays closer attention to detail and colours, experiments more with perspective, and takes risks with more challenging designs." Arafa also points to how the increasingly divergent histories of Gaza and the West Bank are reflected artistically. "Their isolation is so hermetic but we are more open to outside influences, including artistic ones, which also affects our work. You also get the impression that the level of politicisation and party affiliation in Gaza is deeper than it is in the West Bank, which breeds a more vibrant and competitive artistic culture overall."

Muhanned el Azzeh, 27, another local graffiti artist from a nearby refugee camp, expressed appreciation at the opportunity to see the exhibition, taking note of its important role in documenting part of modern Palestinian cultural heritage and political history. "During the 1980s there were thousands of pieces of graffiti put up on walls, but none of that exists any more, and none of what was said in those messages has been recorded. But this is our history - the history of our daily struggles. We need to preserve it both as political expressions and as artistic works."

Grondahl hopes the book and exhibition can contribute to changing the perspective of how many in the West view Palestinians and their struggle. "Most of what is written about Palestine is the same old stuff that we have heard again and again: the settlers, the Judaisation of Jerusalem, the refugees etc. The terrible thing is that people get tired of hearing it, and it's difficult for journalists to find new angles to tell the story. Gaza graffiti tells them something else - things they didn't know about Palestine. I realised that I could reach new people that way, particularly young folks, and that it was a new way to alert an interest in what goes on here."