A November breeze was blowing as my friend Liliane and I walked to the Zamalek Art Gallery in the high-end district of Zamalek in Cairo. A show of works by Adam Henein and his Swiss-born sister-in-law Antoinette had opened a few days before, but classwork at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Helwan University had kept us from attending the vernissage. Surprisingly, the legendary artist himself was seated in a corner, sipping tea in contemplation.

“Let me introduce you,” said Liliane. “You know him?”, I gasped. “No,” she replied, giggling, “but you are a sculptor and you should meet him.” I then accidentally spilled tea all over him. However many times I apologised, he did not seem at all upset and I remember being in awe of his calm, kind demeanour, especially as he insisted we sit down.

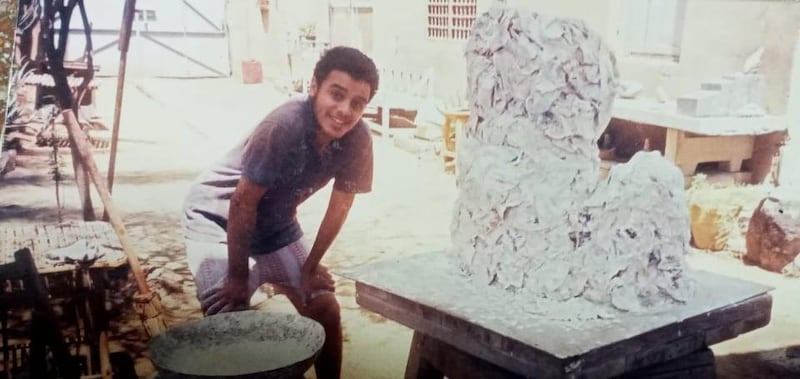

Months later, I ran into him at an exhibition and reintroduced myself, saying I would love his feedback on my work and that I would like to participate in the International Sculpture Symposium in Aswan, which he founded in 1996. He gave me his phone number and said to visit. It was 2004, and I had recently graduated and landed a job at a factory that created sculptures with a "classical Egyptian identity". It was there that I learnt how to handle bronze, but nine months into it, I was not feeling fulfilled, so when Henein invited me to visit, I jumped at the opportunity.

When I walked into his home/museum in Giza's Harraniyya area, Le Repos, a bronze sculpture of a man resting with his arms crossed behind his head, lay on the ground. Its leg was broken, and Henein asked if I could repair it. I set to work immediately and, when I was done, he praised the finish, saying it looked better than it did originally. He did not intend it as a compliment, but I felt a surge of confidence.

Henein asked if I wanted to eat, I said sure, and he then apologised for having only bread and tomatoes, which is what we ate. After some tea, I told him I was not happy at the factory and that I did not feel like I was creating or learning anything. Henein then asked if I would like to work for him.

Just like that. I could not believe it and immediately accepted the offer. I thought a year at the Henein atelier would be fantastic for my career and mind, so I began working with him in May 2005.

Every day was a lesson. There was a maquette of The Reader, one of his iconic sculptures of a seated figure holding a book, and he wanted to produce a large version of it. I set to work at once, remembering the instructions from the factory to do things quickly. He walked over and asked, "What's wrong?", and I smiled and proudly said: "Nothing, Mr Henein, I'll have this ready for you today." He paused in the way he did when he contemplated and asked: "Who said I want it today? I want you to think of it."

At first, I thought it was strange. Didn’t he want the work finished? I learnt that I had to pause, observe, really take the work in, enjoy the process and not aim for its completion. “It’s a seed,” he said, soothingly. “Do you expect a tree? The joy is in the process, my dear boy.”

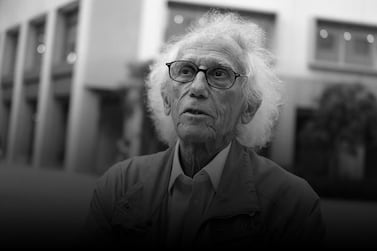

Henein lived a very simple life, almost like a monk, and had a daily regime: he woke up very early to clean the studio before beginning work, took a tea break at 10am, lunched at noon, had tea with biscuits at 3pm and, though I would leave at 5pm, he continued working. His process of contemplation was deeply pensive.

"Put the maquette here Maged, and Abdo, please make some tea," he'd instruct, followed by a long deliberation on the maquette – its proposed size, texture, character and so on. I realised he was creating a relationship between himself, myself and the sculpture. I began observing how he was looking at his work. And, though we considered every aspect of the sculpture – sometimes for days or months on end – the work was not completed until he said it was, until his hand was the last imprint on the piece.

Henein was not a talker. He was a thinker. I had joined his atelier with a million and one questions and tonnes of enthusiasm. At first, his quietness felt problematic, but, pretty quickly, perhaps even unknowingly, we developed a silent language.

Even though he did not speak much, we spoke about everything. We had the same opinion on things, and I don’t know if this came to me through spending time with him or if it was innate. Eventually, I found a way to get him to talk: books. Henein had an impressive library and I would borrow books on the condition that he picks them out for me. That is how I discovered how his mind worked.

I also got to know him by observing how others interacted with him. Ahead of visits, he would have the atelier organised and all the works washed. He was so gracious to visitors and conveyed a deep sense of gratitude for their time. Henein was a force, he drew people to him and, when they orbited around him, they felt compelled to support him unconditionally. Myself included.

He did more for me, though: he helped me find my way, find myself. Because of him, I felt the need and the drive to be an artist in a way that is fundamental, essential even, to my life. But time was passing, and so I could not remain Henein's protege forever. I left his atelier in 2010 and started carving out my own career. I visited regularly and consulted him on pretty much everything.

He would discourage me from living abroad; he would point to the earth and the sky and say: “Look at this soil, look at this palm tree, listen to the birds, observe Egyptian culture.” I’d cite the 25 years he spent in Paris with his beloved wife Afaf Al Dib, when he mostly created paintings on papyrus with natural pigments. “Of course, I benefitted from being in Paris, but I made paintings to survive,” he said. “Who would buy a sculpture by an Egyptian artist in France? Stay here, my dear boy, and celebrate Egyptian-ness.”

I came to understand that Henein's work was inherently and fundamentally tied to nature and the land; that was his faith, his motivation, his raison d'etre. All that he ever looked for and channelled in his art – it was Egypt.

Remembering the Artist is a monthly series that features artists from the region