From MIA and the Memory of Ibn Tulun by Nasser Rabbat

Buildings have memories; memories embedded in their volumes and inscribed on their surfaces, reflected in the modifications, alterations and additions they acquire over time, and recorded in texts or transmitted through tales, songs or images. Some of these memories are premeditated. They are planted in the design and represent a synthesis of the patron's desire, the architect's imagination and the builder's capability. They also link the building to the traditions of buildings that preceded it, which endow it with its historical setting and provide the contours of its own narrative. Most memories, however, are spontaneous and circumstantial. Accumulating over time at no set pace, they attach themselves to the building, thickening its narrative and altering it in a variety of unpredictable yet very real ways.

In its very short lifespan thus far, the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), Doha, has not yet had time to garner many incidental memories, although I am sure it has collected some. Yet IM Pei, its architect, has conferred upon it a powerful foundation myth, one that links it to a fabulous literary tradition, even if he did not intend it. Pei has declared that he found inspiration in the ninth-century Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo. The domed cube of that mosque's ablution fountain, with its logical geometry, rotating segments, clean-cut surfaces and underlying cross-axiality, embodied the essence of Islamic architecture that he was searching for.

The MIA's formal association with the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, however, opens the door to another dimension of signification that this wonderful building epitomises. The stories preserved in the Arabic sources related to the construction of the mosque reveal yet another narrative, one that is steeped in the heart of the Arabic and Islamic consciousness. Retelling those tales, with a healthy amount of imagination and a dash of fabrication, allows me to weave the story of the Museum of Islamic Art into their delightful web of fantasies, myths, parables and half-remembered past.

The story of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun begins with a hidden treasure. One moonlit night, the Amir Ahmad Ibn Tulun went out to the desert with his entourage. Deep in thought, he absentmindedly allowed his horse to wander at will, when the horse suddenly stumbled into a gap in the soft sand. Rising from his fall, the Amir realised that his horse had uncovered an ancient cave, probably Pharaonic, buried in the immense Egyptian desert ...

Nasser Rabbat is the Aga Khan professor and director of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT.

The Cinderella Astrolabe by Jameel Al-Khalili

I have often thought that had I not chosen an academic career in theoretical physics I may well have opted for archaeology - leaving aside of course the fact that I harboured what felt at one time like serious ambitions of becoming a rock guitarist or a professional footballer. No doubt, this love of ancient history was borne out of my having grown up in Iraq, a country that hides under its troubled skin some 7,000 years of glorious civilisations. But I left, or rather escaped, that country of my birth in 1979 without so much as a backward glance. Now, after a career in scientific research and teaching, immersed in the quantum world of atoms, mathematical symbols, computer programs and abstract ideas, I have started to feel a strong and quite pleasant tug to explore my cultural roots. And, as a scientist, my passions have been mostly aroused by a period of history long neglected in the West: a golden age of Arabic scholarship in subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry and physics that began in ninth-century Baghdad.

So my stroll around Doha's beautiful and serene Museum of Islamic Art was probably inevitably going to lead me to those exhibits that would take me back to this age of rationalism and enlightenment that has been obsessing me for the past few years. I found myself surrounded by dozens of beautiful astronomical instruments: astrolabes, displayed alongside each other in row upon row, all seemingly clamouring for my attention, each one more intricate and more shiny than the last.

The astrolabe is an ancient astronomical device originally invented by the Greeks, typically made of brass and the size of a small plate.

I found my object on display behind glass in an alcove on the far wall. The poor thing is not even a proper astrolabe, for the caption underneath describes it somewhat blandly as a "mathematical and astronomical instrument". It consists of a battered and bruised brass disk, about 15cm in diameter, dating back to late ninth- or early 10-century Baghdad. Around the plate are engraved notches signifying angles in degrees, and it has a revolving alidade. Saddest of all its features is a small hole punched in it, looking very much like it was made by a bullet, which I know seems rather unlikely, but nevertheless gives the impression of it having been mortally wounded in battle ...

Jim Al-Khalili's latest book Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science was published in 2010.

Parable of the Tughra and the Mobile Phone by Youssef Rakha

It had been three years since I started researching the Ottomans in the course of writing my first novel ... I was nearing the end of the biggest literary task I had ever embarked on, wholly immersed in the history of the Sublime State. Partly because the story involves messages transmitted through sleep, I was very drawn to Osman I's dream, the legendary prophecy out of which that State is sometimes believed to have sprung.

While still a relatively modest feudal lord in the late 13th century, the man who gave the dynasty its name is supposed to have seen a tree grow out of his belly-button and spread its shade over three rivers, so marking the world's three known continents. Of course, it all came promptly true. Depending on your historical-cum-ideological perspective, my ancestors in the Nile Delta were either pawns or beneficiaries.

The book I was writing is about Cairo, and its protagonist, Mustafa Corbaci, is trying to draft his own subjective map of the megalopolis. Mustafa is visited by the ghost of Abdülhamit's younger brother Mehmed VI Vahdettin (1861-1926/1277-1344 AH), the last sultan and the penultimate caliph, and their meeting gives previously unknown meaning to every aspect of Mustafa's life, down to his name and his cartographic pursuits. After each journey he makes in the course of three weeks in Cairo - the period during which the events of the book take place - Mustafa traces his route across or adjacent to the Nile; he draws with his eyes shut, in order to avoid the influence of reality ...

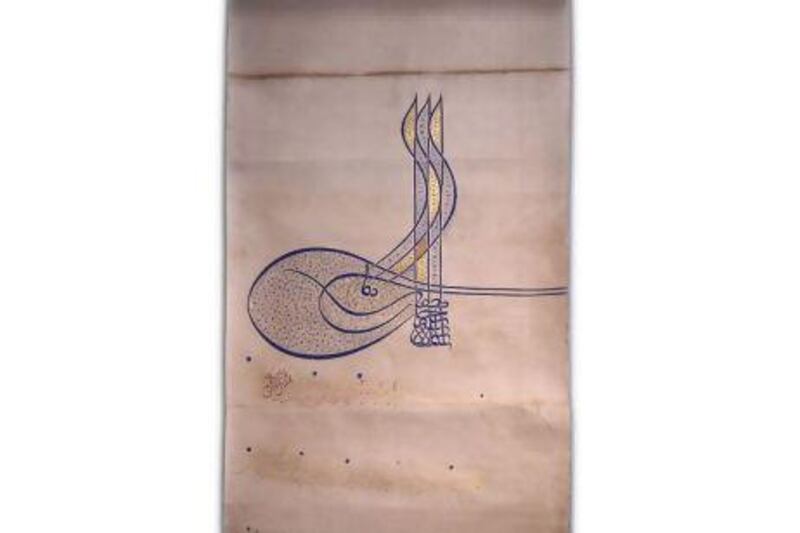

As it turns out, Mustafa's city, the post-millennial Cairo haunted by Islam's last ruling caliph, looks like a tughra: the calligraphic emblem of the Osmanl, which first appeared in the time of Osman's son Orhan I (1284-1359/682-760 AH).

Each "sultan, son of a sultan" had his own individual tughra, a basic design that altered only slightly every time it was inscribed, which spoke his name and worked as both signature and seal ...

A magnificent triumph of the Arabic script, the form combines the Text, Islam's principal reference point, with the Image: abstract but evocative, semiotically loaded but instantly and globally functional. In the 16th century ... the tughra - a work in progress for centuries by now - took on its definitive shape.

Youssef Rakha's latest work is the novel Kitab Al-tughra: gharaib Al-tarikh fi madinat Al-marrikh (The Book of the Tughra). He is a former staff member at The National.