Gita Meh has a love-hate relationship with settling down. The Iranian conceptual artist has moved 146 times and packed up more apartments than she can remember. And, though a wanderer at heart, she nonetheless yearns for a place to call home. Her latest show at Tashkeel Gallery in Dubai, 27 Years of Migration, chronicles her wanderings, exploring issues of identity along the way. It features installations, videos and mixed media work which examine the idea of finding oneself and finding a home.

The result is a large-scale installation piece, Walls, Veils and Voices, which straddles the line between beautiful and frightening. Seven sculptures - or rather rough semicircles made of chicken wire and plaster - are placed in a circle in a darkened room apart from the rest of the gallery. Each sculpture is a little more complete than the next. The installation begins with a wire skeleton, then progresses to a plastered wire frame and ends with the completed sculpture. The final work is a woman's form draped in black with her plaster interior filled with dozens of onions.

Meanwhile, a projector funnels a kaleidoscopic image of zillij, or Moroccan patterned ceramic tiles, onto the walls and the sculptures while Meh's voice resonates throughout the room in calming tones: "This is my surrounding structure; this is my layout." Viewers walking into the room add another dimension to the installation, their shadows looming large on the wall as they stroll past the floor-mounted projector.

The atmosphere may be dark and sinister with the stench of the onions and the mysterious cloaked figures, but Meh says this is not at all her intention. "I'm talking about Middle Eastern culture and our way of life," she says. "I found my culture nourishing when I was far away from it." Meh straddles the boundary between western and Middle Eastern culture and has been in a constant process of learning new languages and cultures to find her place in various societies. Born in Tehran in 1963, Meh has lived in Europe and the United States for half of her life. When she first moved to Los Angeles to attend the California Institute of the Arts, Meh found that her peers and even her teachers had many misconceptions about Islamic culture. Though Meh is from Iran, she played the role of ambassador, explaining the region's culture to colleagues that she says "had no idea about the Middle East".

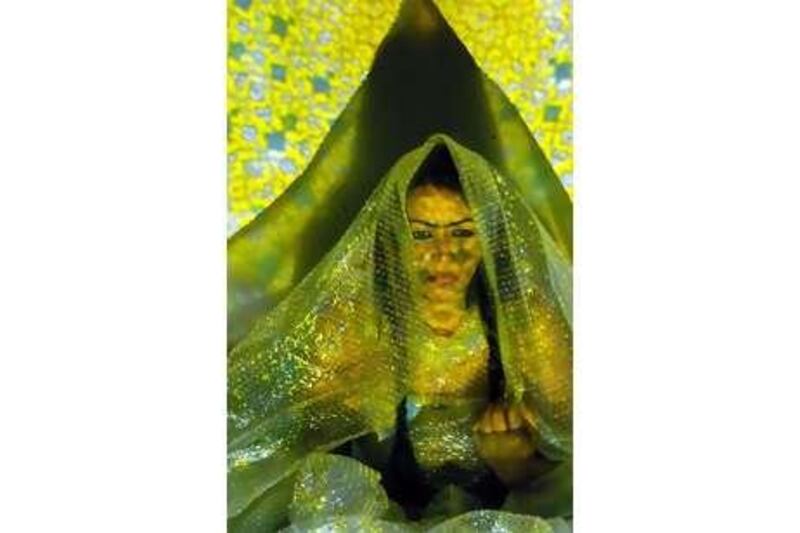

As a victim of her colleagues' stereotypes, Meh became an archetype of the oppressed woman. Rather than launch into a verbal argument, Meh offers her work as a rebuttal, a chance to present a more accurate version of her culture. "I want to be looked at as layers of existence beyond veils or T-shirts and jeans," she says. "We are all more than our facade." Meh has put herself and her own façade at the centre of her photographic series, The Boxed Road: From Los Angeles to Dubai, in which she dons a protective layer of bubble wrap over clothing as if she were a package. In the first image, an expressionless Meh stands in front of a blank white wall surrounded by large brown cardboard boxes in her old Los Angeles home. In others, she is on a blue-painted wooden dhow in Dubai, sitting inanimate among the suitcases and tarpaulin bags.

Standing tall in her bubble-wrap, Meh sometimes wears an expression of dignified determination and, other times, a cool detachment reminiscent of Cindy Sherman's film stills. One of the most compelling photos on display shows Meh standing on a barge, her striking features framed by a metal grille, sky-blue paint peeling off the decorative metalwork. Though she looks wary in the images, Meh actually holds the idea of migration in high regard.

"What inspired me was that I had moved from city to city, continent to continent and if I'm not moving I'm idle," she says. "And if I am idle, I don't go through the process of evolution." Meh compares herself to a fish that must continue to swim in order to stay alive. Indeed, there is an element of movement, whether implied or actual, in nearly all of Meh's work at Tashkeel Gallery. Another series of 56 small warmly lit colour photos compiled into one larger Eadweard Muybridge-style print, called The Boxed Road: Maps No More, features Meh in her bubble-wrap veil sporting Pocahontas braids, twirling, unwrapping and rewrapping herself frame by frame.

Her video installation In Herknowlogy features a group of four sculptures, black-veiled figures with monitor screens as faces standing across from each other. Meh's voice whispers to viewers: "I saved my history into the hard drive of my soul." Meanwhile, images of a bright red apple decorated with gold Farsi script pop up as stills on the monitors, then begin to spin wildly. Meh says Herknowlogy represents the dialogue between technology and theology, but the installation has a kind of sci-fi horror film aesthetic as apple heads whirl frenetically inside the hoods of the female figures.

It is work that demands a lot from the viewer and takes time to decipher; it is not decorative or pretty in the traditional sense. Meh says she thinks of installation art as a less tangible art form that suits her work's concerns: mortality, nourishment and the passage of time. "It's true that the Middle East is very paint-orientated," says Meh. Installation art is still something of an anomaly in Dubai. Jill Hoyle, the manager of Tashkeel Gallery, says, "I don't think installation art is frequently shown here, but she's dealing with such interesting concepts and ones that affect so many residents in Dubai that it's worth exploring them."

In a place that is trying to decipher its own distinctive visual culture, art that leaps off the canvas and into the viewer's personal space is sometimes seen as somehow antagonistic. Installation art forces the viewer to interact with it in a way that can be not only mentally uncomfortable but physically uncomfortable as well. But the same feelings that installation art provokes are also what make it interesting.

"I think if art is for the people then they should be a part of it," says Meh, and Walls, Veils and Voices, engages the viewer on a number of different levels, from sculpture to dizzying pattern projections to the smell of the onions, which has become rather pungent since the exhibit was mounted in mid-October. "Gita is a conceptual artist whether she's painting or working on sculptures, installations or her photographs," Hoyle says. She describes Meh's work as accessible but challenging, though not controversial.

"You can still relate to some of the issues that are relevant to women all over the world," Hoyle says. "Gita's experience is very much a blend of the East and the West and she really does bring the two together through everything that she does. I think there are ways you can respond to them as a woman without necessarily being an Arab or Muslim woman, or a woman from this region - the issues are relevant to women all over the world."

Meh has found a home among the diversity of cultures in the UAE and settled in her new habitat. She has been delving further into the idea of constructions of identity and the self. "I was working until three or four in the morning creating this new installation," she says. "And the whole concept happened here in the UAE." Though Meh's work centres on transitions, she says that she prefers being settled, particularly here.

"Dubai is it for me, because I am neither Eastern nor Western anymore," she says. "Dubai gives me the ability to be both at the same time."

swolff@thenational.ae