This month sees the opening of an eagerly awaited exhibition at London's Royal Academy of Arts. The Real Van Gogh: the Artist and his Letters will shed new light on the life and work of the painter and is the first major Van Gogh exhibition to be hosted in the city for more than 40 years. The exhibition will show a selection of Van Gogh's letters alongside the works they make reference to and will make use of a new edition of the artist's correspondence, produced by scholars at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam over the course of the past 15 years.

It's the closest we have to an artist's commentary on the work and will offer audiences a rare glimpse into the mind of one of the most celebrated painters in modern history. The title of the show makes clear its intentions, aiming to uncover an artist too frequently fictionalised as a crazed psychotic whose tormented life produced artistic brilliance and ended in suicide. Including more than 35 original letters, 65 paintings and 30 drawings, the exhibition is already being hailed as a cultural highlight of the year. Van Gogh's work has sold for up to $82 million (Dh301m) at auction and he remains one of the most popular artists in the world - both factors that have contributed to the 40-year wait for a major Van Gogh exhibition in London.

"Paintings by Van Gogh are extremely difficult to borrow," says Ann Dumas, the show's curator. "They're very valuable. When they are in permanent collections, often those collections are reluctant to lend them because they're frequently the favourite works and people go especially to see them. There have been other Van Gogh exhibitions in other parts of the world but because of his great popularity and his greatness as an artist, it's very difficult to assemble a substantial number of his works."

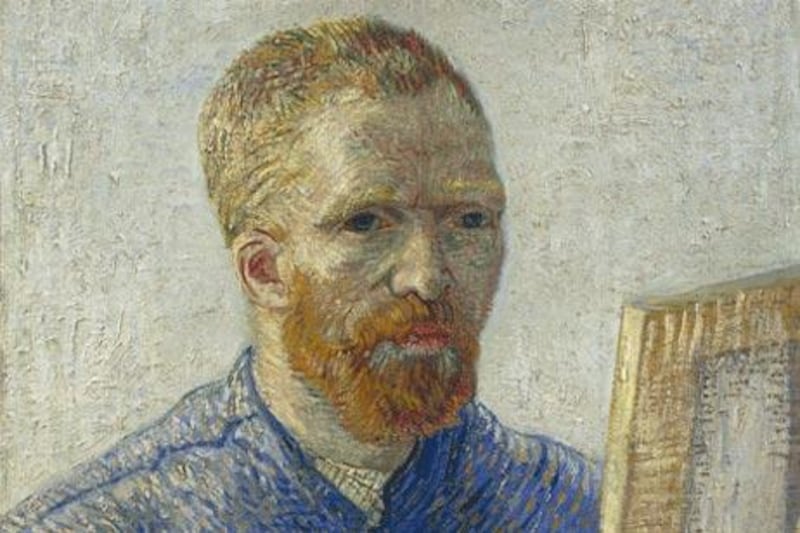

Big lenders to the show include the Van Gogh Museum, the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, as well as other museums and private collections worldwide. In an exhibition underwritten by pathos and humanity, highlights are set to include Self-portrait as an Artist (1888), The Yellow House (1888), Still-life: Drawing Board with Onions (1889), Vincent's Chair with His Pipe (1888), and Entrance to the Public Park in Arles (1888). Audiences will be confronted by star-laden scenes, swirling skies and brightly coloured sunflowers; all testament to Van Gogh's aesthetic appreciation. This artistic sensibility is implicit in the letters, advising his brother in one instance to "find things beautiful as much as you can, most people find too little beautiful".

Since his death in 1890, Van Gogh has remained something of an enigma. Part genius, part depressive, the Dutch artist was one of six children of a Protestant pastor. Following a stint working for an art-dealing firm, he signed up as a missionary before turning to painting in 1880 at the late age of 27. In the 10 years before his death, Van Gogh produced more than 800 paintings and 1,200 drawings.

The fact of his prolific creativity being reflected in a series of tempestuous relationships and eventual confinement in an asylum is well documented, but The Real Van Gogh strips away the myth and goes beyond popular histories. Van Gogh, we discover, was a frequent and eloquent correspondent and one who would include sketches of artworks in progress in his letters. The epistolary form was a comfort to him and a way of narrowing the geographical distance between his family. In a letter to his brother, Van Gogh says: "Familiar handwriting makes one feel firm ground beneath one's feet again."

Recipients included his sister and friends such as Paul Gauguin, Anton van Rappard and Emile Bernard. The bulk of letters are, however, addressed to his younger brother Theo, an art dealer who supported Van Gogh financially and emotionally throughout his career. The letters speak of art, nature and literature. Far from being the erratic ravings of a madman, the articulate correspondence is regularly punctuated by moments of real insight and clarity. In detailing and sharing his intimate thoughts and observations, Van Gogh - or his letter-writing persona - shows evidence of determination and sensitivity.

The letters bring the more familiar works to life in new ways, exploring the vibrancy and luminosity of Van Gogh's paintings and their ability to capture mood and emotion. In a letter to his sister dated 1888, Van Gogh describes both his unique vision and his acute awareness of his own difference. "Most painters," he writes, "because they're not colourists, properly speaking, don't see these colours there, and declare that a painter who sees with other eyes than theirs is mad."

Dumas says of the letters: "They really are an extraordinary insight into the way Van Gogh thought about and made his art. The thing that comes out most strikingly is that he was a very thoughtful and reflective man who studied and read a great deal about art. He thought about colour theory, technique, and philosophical ideas." She adds: "The received public myth of Van Gogh is that he was this crazy artist who cut off his ear and eventually killed himself - both of which are true - but it has coloured people's vision of him as a whole.

"You learn from the letters that he was anything but mad. He was an extremely intelligent, highly cultivated man, fluent in four languages, extraordinarily well read, and very well versed in literature and art."