Ion Barladeanu was a name unknown to the art world until very recently. Before 2008, the 63-year-old Romanian was eking out life on a grubby mattress at the bottom of a garbage chute in a Bucharest housing block. It is a world away from the surroundings in which he found himself last week, at the Anne de Villepoix gallery in Paris for a soirée privée, and not just any soirée privée. It was his own.

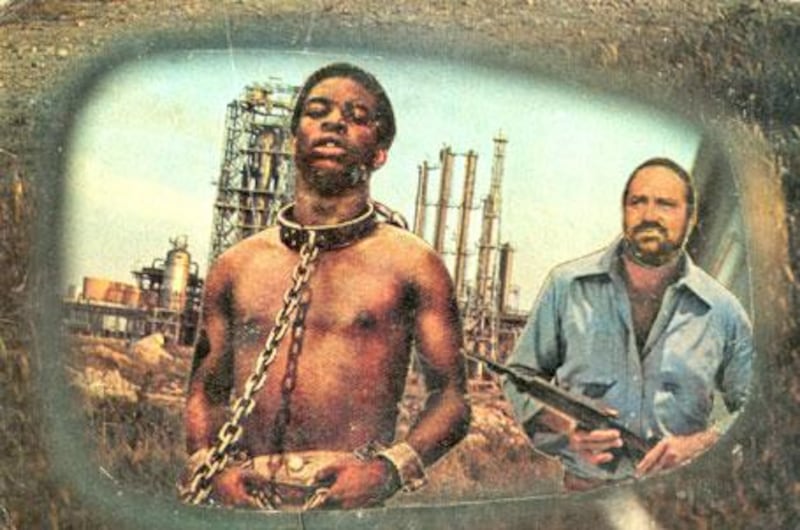

On display at the gallery are collages created from discarded magazines that Barladeanu has rifled through for many years. It is a line of work, in fact, that he began before the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989. Created with a cinematographic edge, they depict shiny possibilities outside the gulag-like background in which he sets them. It's work that would have landed him in danger for many years. So he earned small pay packets through menial work as a grave digger and manual labourer, piecing his collages together in secret. It wasn't until 2007 that he showed them to another artist, who was also found scavenging through the rubbish. The fellow artist, in a cheering display of solidarity, called up a gallery owner to alert him to his find. The works are now on sale in Paris for around ?1,000 (Dh5000) each.

Barladeanu now has a new flat and a new set of dentures. Last year, he was flown to Art Basel. In February, he was brought to Paris for the show, titled Realpolitik, and in the ultimate accolade for a burgeoning artist, surely, he had lunch with Angelina Jolie. One presumes that a Hollywood screenplay is being scribbled out this very second, starring Brad Pitt as the toothless vagabond. You can smell the Oscar already.

There is possibly something distasteful about plucking a man from homeless obscurity in Romania, dressing him up and parachuting him into Parisian society, with A-list celebrities fawning at their latest darling. Barladeanu is far from the first artist to come to fame after a life far outside the art world. Bill Traylor was born a slave on a plantation in Alabama in the mid-19th century. He was poor and illiterate, his mother tied him to a tree as a small child while she worked in the fields, he killed a man his first wife was having an affair with, he fathered a son later killed by the Ku Klux Klan and he spent years at the end of his life homeless and sleeping between empty coffins in a funeral home. And yet during a three-year span in his 80s, he produced more than 1,500 simplistic figure drawings, and is now feted by art historians as offering a fascinating illustration of Jim Crow America.

The stories of outsider artists are necessarily often of struggle, because they have forged their creativity without help or education. Adolf Wolfli, born in 1864, was another of the earliest artists to earn the official label of outsider. He was abused as a child, orphaned aged 10, later spent time in prison before being placed in a Swiss asylum. There he started to draw, and was given a ration of one pencil a week. He was soon allowed more supplies, as it was observed that his temper calmed in the process. He was prolific, churning out thousands of illustrations that are now housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Berne.

Henry Darger is another name. He, too, had a difficult childhood and was institutionalised in a Catholic boys' centre until he escaped aged 16. He lived in Chicago for the rest of his life, working in a Catholic hospital. But it wasn't until his landlord barged into his apartment, after his death, that among nearly 1,000 balls of string and hundreds of Pepto Bismol bottles, there was a vast accumulation of artwork, the central element of which was an illustrated tale of 12 volumes and 19,000 pages.

Among stories such as this, Barladeanu may well be thankful that Angelina and company are his new patrons, and no doubt he is grateful to have given up the mattress. Whether or not his work continues to be so significant is another matter. * The National