In the summer of 1940, British officials received reports that large crowds had begun to gather in Sharjah to listen to Arabic language radio broadcasts by the German government. It was even reported that pro-German slogans had been found written on walls in the town. Although the existence of pro-German sentiment in Sharjah, then a part of the British-controlled Trucial Coast, may now appear incongruous, when viewed in the context of the large-scale propaganda efforts that the German government directed towards the Middle East before and during the Second World War, it appears less surprising.

Between 1939 and 1945, the German government broadcast Arabic radio to the Arab world seven days a week. In these broadcasts and other propaganda material, Germany made a concerted attempt to portray itself as a friend of Islam and as a supporter of anti-imperialist movements opposed to the British Empire. Unsurprisingly, this message found a receptive ear among some entities that were then under British colonial rule; notably so after the fall of France in May 1940, when the prospect of Britain losing the war appeared a likely outcome to many.

In response, the British government launched its own propaganda campaign in the region. As one component of this, Britain's wartime propaganda organisation, the Ministry of Information (or MOI), disseminated an extraordinary assortment of material throughout the Arab world during the war. A selection of this Arabic material has now been released in Persuading the People: British Propaganda in World War II. Published by the British Library, the MOI's role is explored by Professor David Welch, director of the Centre for the Study of Propaganda, War and Society at the University of Kent in the UK. The book is illustrated with fascinating examples of the posters, pamphlets and other materials disseminated around the world, including the Middle East.

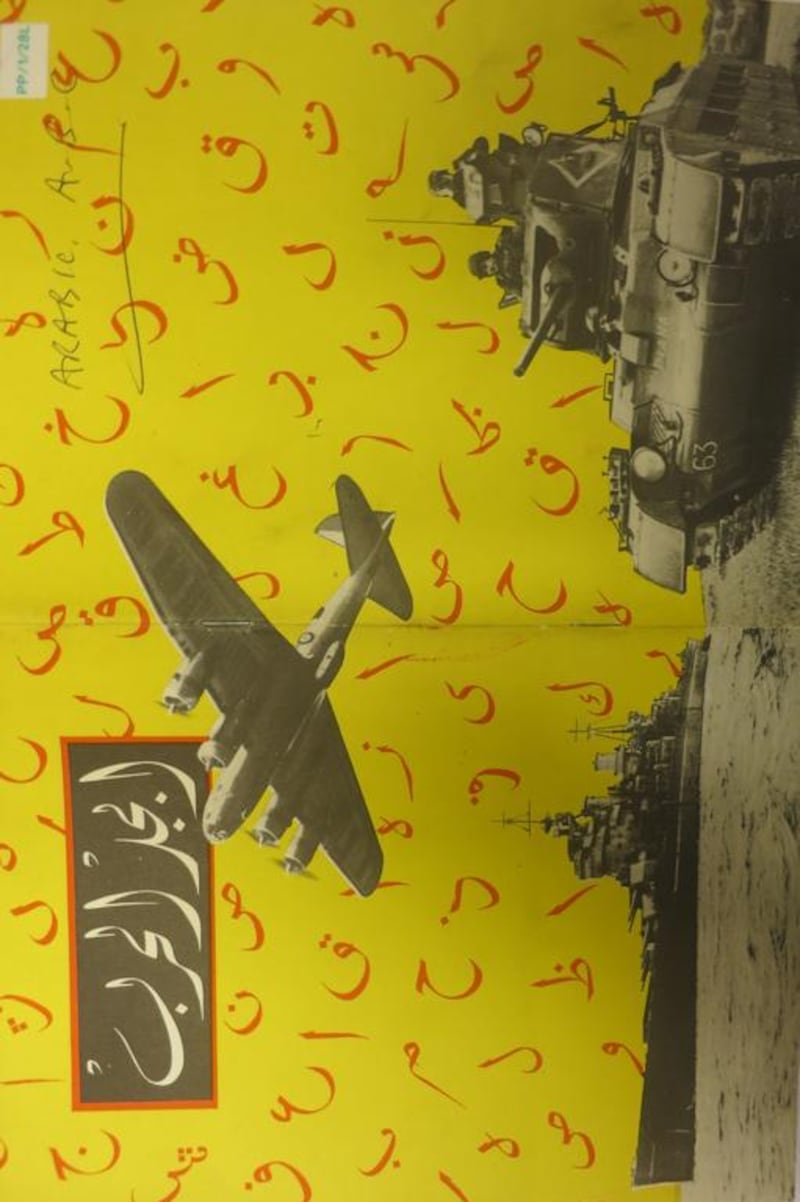

One of the most interesting examples of what the MOI produced is a pamphlet titled The Alphabet of War, containing an illustrated entry for each letter of the Arabic alphabet. The entries are a curious assortment of places, people, armaments and concepts that project an image of Britain as the last "bastion of freedom" on the path to victory against the Nazi regime and its allies. Unlike many of the MOI's other publications that were written for a general audience and then translated into several different languages, this pamphlet was written specifically for the Arab world. In the entry for Hitler, the Nazi leader is described as the "arch-enemy" of God and the entry for treachery states that he is trying to "enslave the world". The entry for corruption portrays the Nazis as morally degenerate, its soldiers depicted drinking alcohol and dancing with scantily clad women – an image obviously intended as an affront to the religious beliefs and perceived social conservatism of the Arab world. As noted by a British official at the time, Germany and Italy had the "advantage of being able to make wild promises to the Arab world regarding freedom, independence and redressing the wrongs inflicted upon the Palestinians". Therefore Britain tried to utilise religion in its favour, in this context, an MOI official remarked "we must show that the Nazi faith is the very antithesis of religion".

The entries for Iraq and Egypt stress that they are independent countries allied to Britain against the Axis powers. This neatly overlooks Britain’s invasion and occupation of Iraq in 1941 and its much-resented position of colonial dominance in Egypt as per the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936. Overstating the point and seemingly conscious of its hollowness, the entry for Iraq stresses the country is “an independent Arab state with total independence”, while Egypt is described as “a completely sovereign and independent state”. Both countries are misleadingly depicted as loyal allies and friends of Britain in the war effort. The booklet also references Britain’s aerial bombardment of German cities. The entry for planes describes bombers as “messengers of wrath raining down woe and destruction on the heart of Germany”. This violent tone continues in the entry for force, which is described as the only thing the Nazis understand. The final entry in the pamphlet, despair, leaves the reader with little doubt that Hitler will be defeated and that Britain and its allies will be victorious.

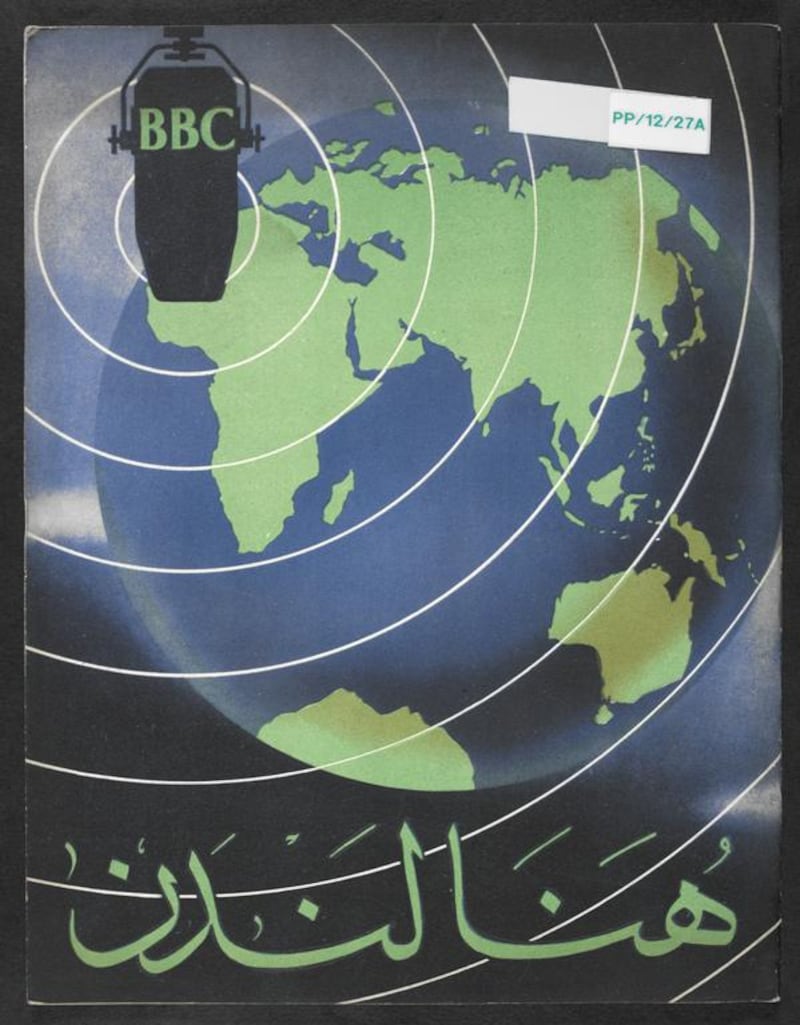

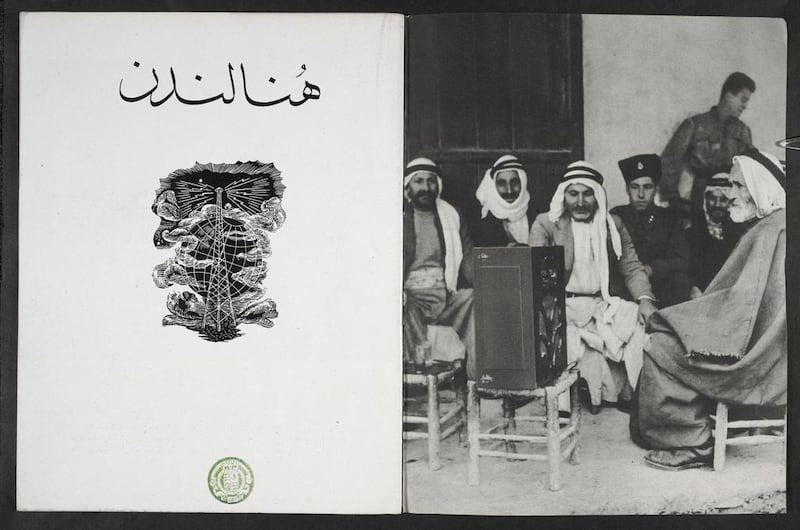

In 1938, in response to Arabic radio broadcasts of the German and Italian governments, Britain established BBC Arabic radio, the BBC's first foreign-language station. Subsequently, the MOI produced the pamphlet This is London that promoted the new station and its broadcasts. The pamphlet contains details of the official opening of a mosque in Cardiff in 1943 – an event that was attended by Hafiz Wahba, Saudi Arabia's representative in London, and was broadcast by BBC Arabic. As part of its attempt to use religious sentiment to its benefit, Britain was keen to stress that the country's Islamic community were free to practise their faith and to open places of worship.

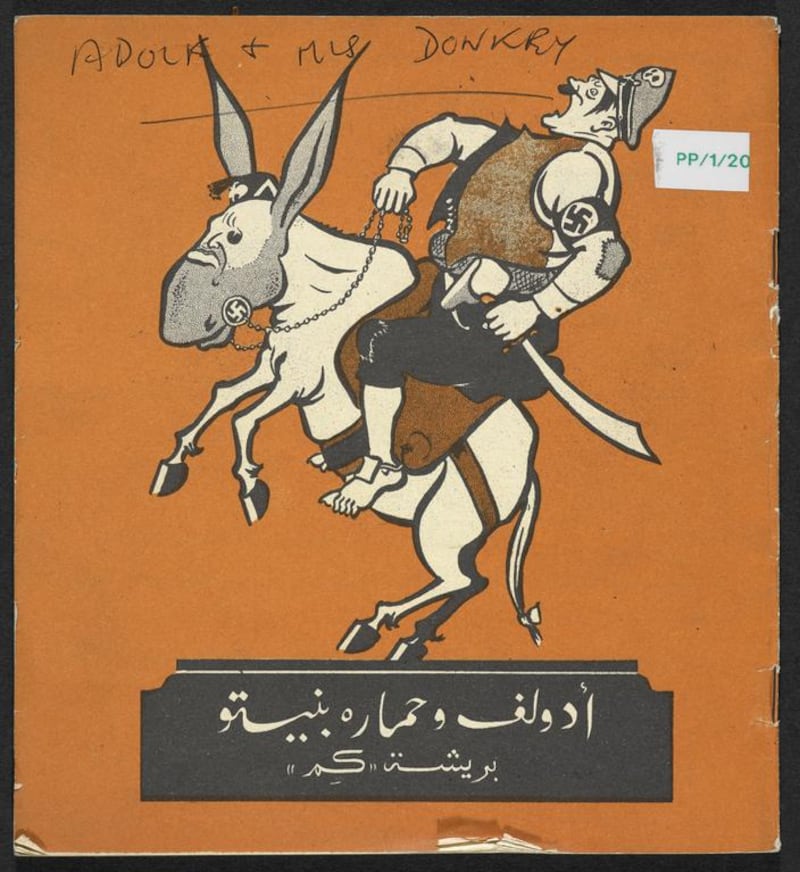

The MOI also produced cruder propaganda, notably a series of satirical cartoons titled Adolf and his Donkey Benito, which depict Hitler as a bumbling fool riding his unfortunate donkey, Benito (an obvious anthropomorphic representation of Mussolini). As well as being distributed as pamphlets, these cartoons were also inserted into newspapers in the Arab world, including the Bahraini newspaper Al Bahrain, which was controlled by Britain at this time. One of the cartoons in the series depicts Mussolini as afraid of confronting a tiny Greek mouse, an obvious reference to Italy's unsuccessful invasion of Greece in 1940-41.

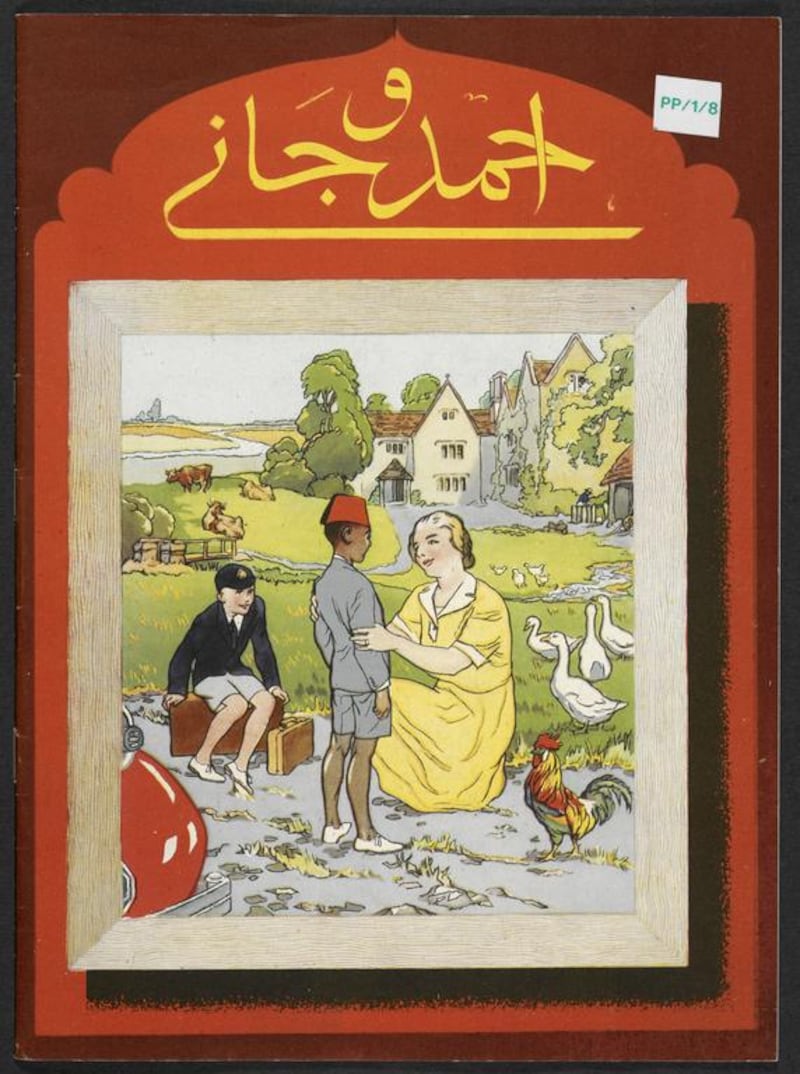

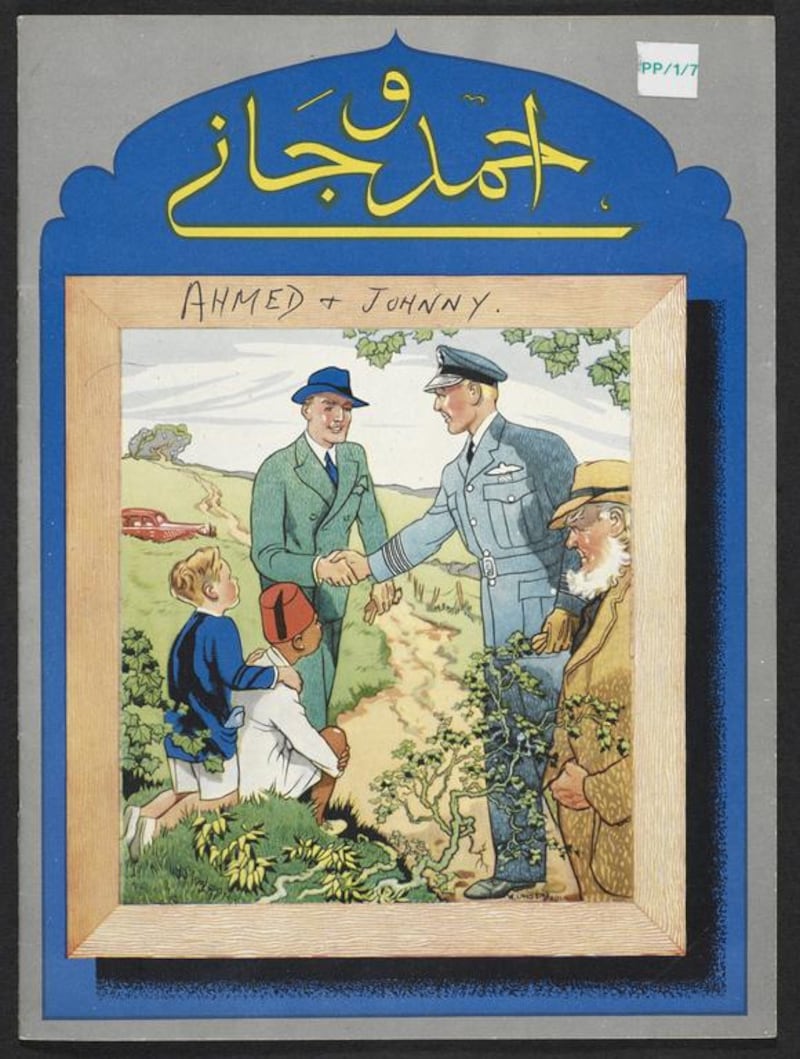

In an attempt to target children, the MOI also produced a series of short stories called Ahmad and Johnny. These stories were illustrated by William Lindsay Cable, an illustrator best known for his work in the books of the famous children's author Enid Blyton. In a manner reminiscent of Blyton's work, Ahmad and Johnny follows the adventures of Ahmad, a Sudanese boy living in England with Johnny and his family. In one issue, the two boys go for a walk in the Kent countryside, where they bump into a farmer whose son is said to be serving in the British military in Sudan. Britain is described as the "home of freedom" and the "source of hope of the future". Ahmad and the farmer compare life in England and Sudan, and the ostensibly friendly relations between the two nations are stressed.

In the same story, Ahmad and Johnny meet a British pilot who tells them the story of his life. He begins with a personal reminiscence about learning to fly but soon shifts into a simplified account of the Battle of Britain. As the pilot finishes, Johnny’s father appears, shakes his hand and proclaims that he and the other British pilots will be remembered as “immortal heroes of truth and justice”.

Ultimately, the diverse materials the MOI produced are testament to the multifaceted propaganda effort that it carried out – one which used the skills and expertise of British academics, cartoonists, authors and many other skilled professionals. It was a campaign that sought to belittle Britain’s enemies and project an image of the country as a righteous, commanding military power that was close to victory against the forces of evil. In the context of the Middle East, this entailed a cynical attempt to portray Britain’s military occupation and colonial domination of the region as merely “brotherly” friendships between allies.

Ironically, in 1948, a British official in the Arabian Gulf bemoaned the manner in which the MOI had popularised self-expression as a counter to Nazism as a “weapon of war”. He argued that this effort had increased the Gulf’s inhabitants’ knowledge of the world’s problems, “particularly of the rights of small nations and the independence of Arab nations” and was causing them to question Britain’s dominant position in the region.

Louis Allday is a PhD candidate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and a Gulf history and Arabic specialist for the British Library-Qatar Foundation Partnership, a project digitising British colonial archives of the Middle East, held at the British Library.