It is easy to bemoan the prospect of a penalty shoot-out to decide any football contest, but difficult to not enjoy – or at least become unhealthily involved in – the spectacle of watching it.

The question of whether shoot-outs are fair (a glib question that presumes life is also fair) has never been off the table once it was first placed on it internationally in 1970.

Although individual countries had tried shoot-outs before, that year Fifa proposed the recommendation to the International Football Association Board (IFAB), the guardians of the laws of football.

Reluctantly, the minutes of that meeting record, they recommended its acceptance "though not entirely satisfied with the proposed new methods".

In this unresolved space the shoot-out has since remained: approved in letter, unaccepted in spirit. Lawmakers had little choice back then, given that they used to draw lots to break ties before.

Periodically the question is shoved to the table's centre, usually after a major final is decided thus or an international tournament looms. We are in between both.

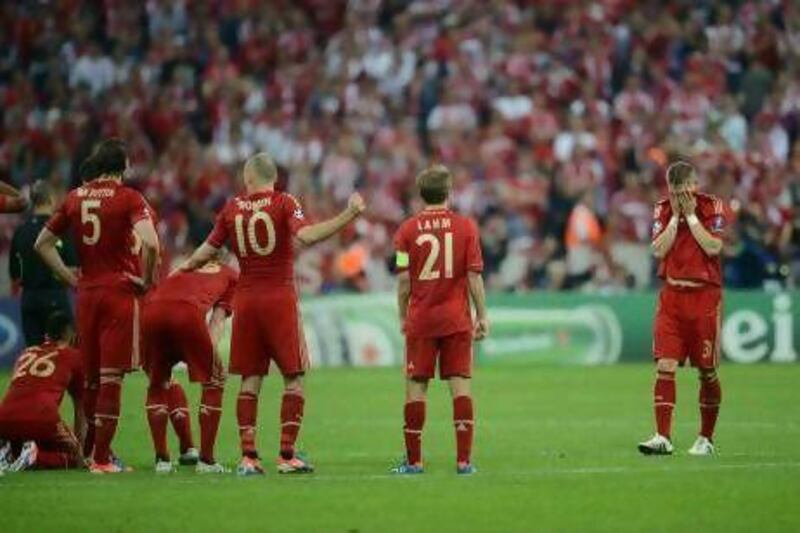

The thing about shoot-outs is that they can be particularly unnerving because they force empathy. You can watch a football match in its own context, without identifying with a team or player, and appreciate it for what it is, even a goalless draw. Throw in a shoot-out and the world changes.

Now you are compelled to pick sides because the suddenness of it, the finality, creates instant and extreme emotion and identification. It forces closure and many times you don't want, let alone need, closure. Ambiguity and open-endedness is just fine.

For practicality though, tournament play demands a result so there has to be some way to settle matters. One predominant and recurring criticism of the shoot-out is to liken it to Russian roulette. This is misplaced because that is a game of probability in its purest form; drawing lots was Russian roulette.

However reductive shoot-outs are, both penalty taking and penalty saving require a skill and a specific, steeled thought process.

If it was just down to chance, then Holland and Germany, to name just two big footballing nations, would not have such records as they do: Holland have won one of five shoot-outs, Germany five of seven (they have only ever missed five penalties in shoot-outs).

Not surprisingly when Sepp Blatter, the Fifa president and a long-time sceptic, called yet again recently to scrap the shoot-out, the German Franz Beckenbauer rejected it the next day.

Of late, the shoot-out has become an obsession of sorts for some. Entire websites are dedicated to them; the world of academia has produced several papers; two well-regarded books have been published, On Penalties by Andrew Anthony and Gyuri Vergouw's Strafschop: The Quest for the Ultimate Penalty. This in itself is revealing of the impact shoot-outs have, particularly on sides that lose them serially. The two books, it is no surprise, are written by an Englishman and a Dutchman.

There are alternatives. Some, like tossing a coin, can be dismissed outright. Some, like having a panel of judges assess and award a game on points, sound intelligent and worthy but are unrealistic. You only have to look at boxing to imagine the mess this might create.

How else? Tot up key statistics at the end of a game (number of corners won, share of possession, number of shots on target and so on) to decide? This feels incomplete and arbitrary: such statistics don't always reveal a definitive or deserving winner. Maybe you could decide on the basis of goals scored, or goal difference, from previous rounds.

A more creative and credible option involves reducing the number of players on each side progressively over extra time. Theoretically this leaves more space and thus the potential for more goals, although in reality it does not guarantee the latter.

A personal favourite is the ice hockey-style tiebreak, allowing one player to start from the halfway line and take on the goalkeeper one-on-one within a time limit.

The Americans tried it in the 70s and 90s but abandoned it both times. One ingenious variation is the idea of Timothy Farrell. The ADG solution (Attacker Defender Goalkeeper – and yes, there is a website) designates 30 seconds to an attacker to beat a defender and a goalkeeper, each side with five attempts (thus involving all active players and a greater degree of tactic and strategy).

Germany, of course, would probably still win it in the end.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]