If UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt decides against an increase in defence spending in Wednesday’s budget, it will demonstrate that the government is “more interested in votes than defending Britain”, analysts have told The National.

With the UK’s depleted armed forces in a “critical position” and the threat of a land war against Russia increasing, neglecting the nation’s defences would mean “Britain won’t deter anybody”, said retired British Army colonel Hamish de Bretton-Gordon.

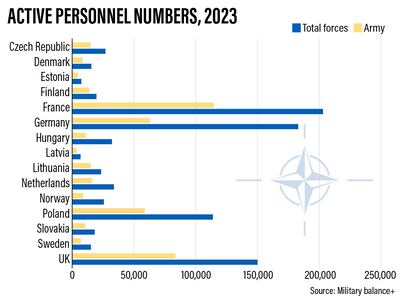

The British Army in particular is in a weakened state, being reduced to 72,000 soldiers at a time when the war in Ukraine has demonstrated that large numbers of troops and equipment are vital.

Defence analysts have compared Britain’s position – and indeed much of Europe’s – to the small, poorly equipped British Expeditionary Force that was roundly defeated by the Nazi panzers in France in 1940.

There are also growing calls for a major UK defence review to realign the forces to the threats now faced, although that is unlikely to take place until after the general election later this year.

If the defence budget remains unchanged, Mr de Bretton-Gordon said this would be “a real disappointment, demonstrating that the politicians are purely interested in the election rather than defending Britain and preventing a war in Europe”.

‘Pre-war generation’

While Defence Secretary Grant Shapps has warned that today’s youth are a “pre-war generation”, retired brigadier Ben Barry, of the International Institute for Strategic Studies think tank, said both Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Mr Hunt “had been conspicuous in their absence of stepping up to say, we agree”.

However, the government has in the past year committed an extra £2.5 billion ($3.16 billion) in real terms to the defence budget.

But Britain needed to prove it had a “credible defence”, otherwise it would become “horrifically irrelevant, especially if we don't stop Putin in a conflict in Europe”, Mr de Bretton-Gordon said.

“We have a pretty small stick to beat [Russia's President Vladimir] Putin with at the moment.”

Mr Barry was the lead UK analyst behind the IISS’s annual Military Balance report on the state of global armed forces. Since writing the British military entry, he said that the force was “more hollowed out than I thought, particularly in terms of manning and training”.

Extra budget money could rapidly “rectify many weaknesses” by “rapidly rebuilding military capability”, procuring ammunition stockpiles, spare parts and improving readiness.

He also highlighted less obvious issues. For example, 30,000 personnel were deemed “dentally unfit to deploy on operations” because dentists had been diverted to thousands of Ukrainian troops being trained in Britain.

“The traffic light should be flashing red, and there should be urgent work being done to rebuild the weaknesses in military medical capability but there is no sense of urgency,” said Mr Barry.

Boots not cyber

Ukraine had debunked the hope that wars could be fought with “technology, cyber and space” with “boots on the ground” turning out to be key, Mr de Bretton-Gordon said.

He suggested that defence spending should be a minimum 2.5 per cent of GDP and rise to 3 per cent to “have an army of mass that will allow us to deter future aggression, and deter Putin”.

Many European countries do not make the Nato 2 per cent threshold for defence spending, while Russia’s is 7 per cent and America’s 3 per cent.

Britain can also barely field an armoured brigade – let alone an armoured division – for Nato’s defence and its army should also be increased to between 90,000 and 100,000 troops, the analyst said.

The army was also facing a retention crisis with officers and soldiers leaving, fed up with poor accommodation, medical care and generally low morale.

“The threats at the moment are higher and worse than they've ever been, even during the Cold War,” Mr de Bretton-Gordon said.

“We have an army of 72,000 men which we can't even man and retain, which just shows what a critical position we are in.”

Nuclear out

With the submarine-launched nuclear deterrent using up an estimated 26 per cent of defence’s £46 billion ($58 billion) spending, there are increasing calls for it to be separated out from budget, as it was for much of the Cold War.

“Nuclear deterrence is a national matter and it should not eat up a quarter of defence spending,” leading military analyst Paul Beaver said. He suggested it could be managed by the Cabinet Office, which already has 150 technical defence specialists.

Mr Barry agreed, adding that the money spent on the next generation of Vanguard submarines and their missiles was “absolutely staggering and subject to very little scrutiny”.

Better homes

Mr Beaver argued that the forces had enough money but it had been badly spent on unnecessary capabilities, despite the UK having the biggest budget in Europe.

“We don't spend it very well and we just don't get value for money,” he said.

“We can't have bigger armed forces until we can man the existing ones,” he added.

“We've got to have a better deal for personnel, spending money on housing and sorting out married quarters.”

A defence review was rapidly required, agreed Mr de Bretton-Gordon, because the war in Ukraine had “fundamentally changed the landscape”.

Britain had spent too much time and money concentrating on the “wrong kit”, including “clever cyber” equipment.

“On the battlefields of the Donbas [in eastern Ukraine], tanks and fighter jets are the currency that makes a difference,” he said.