Liz Truss's resignation as Prime Minister brings an end to the shortest, and one of the most remarkable, premierships in modern British political history.

Her time in No 10 Downing Street lasted just 45 days after Conservative Party MPs moved against her over her disastrous handling of the economy.

In truth, Ms Truss, 47, was her own worst enemy. She admitted she went “too far, too fast” in her pro-growth, tax-cutting mission at a time when Britain faced a profound fiscal crisis.

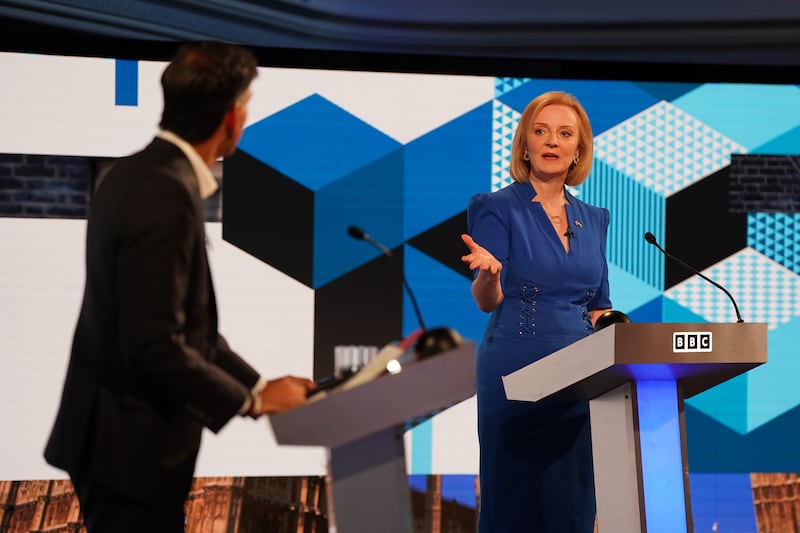

A libertarian whose free market views were shaped by right-wing think tanks, Ms Truss believed her unpopular supply side reforms — including reducing the tax burden for the wealthiest and ending a cap on bankers' bonuses — would restore growth to a stagnating economy.

Her political death warrant was signed during her first days in office by appointing ideological soulmate Kwasi Kwarteng as Chancellor of the Exchequer and removing civil servants who might scrutinise her radical plans, including the permanent secretary to the UK Treasury, Tom Scholar.

Their calamitous mini-budget, which included billions in unfunded tax cuts, rocked financial markets, pushing interest rates higher as the pound tumbled to near parity with the dollar.

The Bank of England stepped in with a £65 billion ($73bn) emergency bailout to shore up the gilts market and support heavily leveraged pension funds that had gambled during the era of ultra-low bond yields.

Britain's borrowers and mortgage holders also faced paying hundreds more on their monthly bills at a time when energy costs and inflation were already eating into pay packets. The Conservative Party's reputation for economic competence was shattered in the span of a few days.

In a bid to save her own skin, Ms Truss sacked the Chancellor but her subsequent faltering media appearances stoked fears she lacked the leadership skills to restore credibility in her government.

The appointment of Jeremy Hunt as Chancellor resulted in an unprecedented policy U-turn that saw virtually all of her economic programme scrapped, including the pledge to cut corporation tax and reverse rises in National Insurance payments.

The gamble of “Trussonomics” backfired spectacularly, with a new era of austerity being touted as ministers attempted to appease markets and plug the hole in the nation's finances.

Conservative politicians began to plot against her after dire polling numbers showed the party heading for annihilation at the ballot box as Labour surged to an average 30-point lead.

During her maiden conference speech as Tory leader, Ms Truss batted away criticism and issued an attack on her opponents, calling any sceptics the “anti-growth coalition” who were holding Britain back.

She denounced a large section of the electorate, including environmentalists, “militant unions” and “Brexit deniers” who she claimed were out of step with the wider nation.

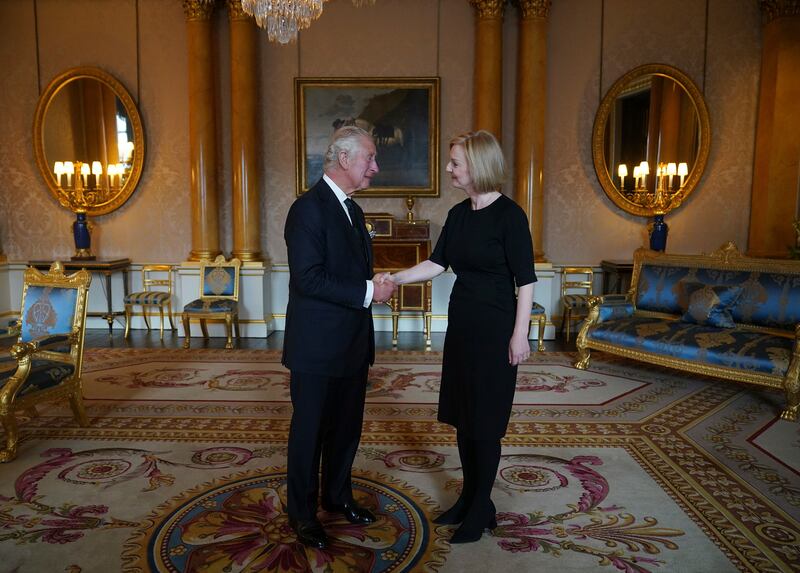

Those sympathetic to Ms Truss will point out that she faced a difficult start to her time in No 10 after the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

Racing to catch up, she sent Mr Kwarteng to announce a radical shake-up of the economy to fuel growth but in doing so sent markets into a tailspin.

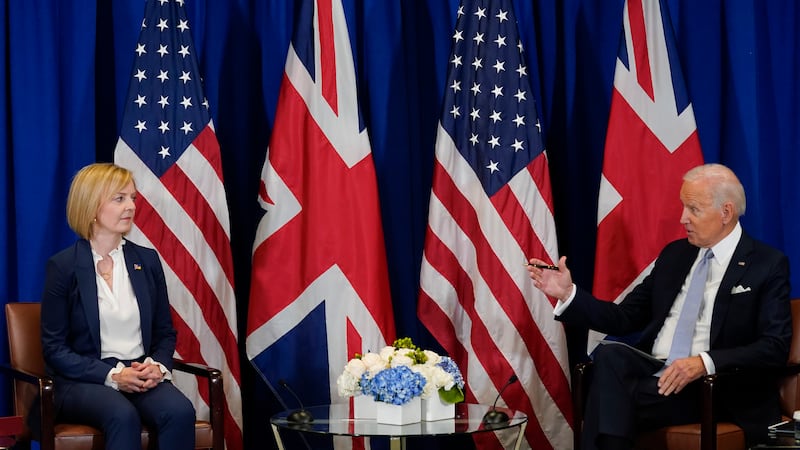

Ms Truss prided herself on extending a government-backed energy price cap to £2,500 to help families with soaring heating bills, and will be remembered for her robust support for Ukraine as foreign secretary and later as Prime Minister.

Watch: UK Prime Minister Liz Truss apologises for mistakes

Born in Oxford to a maths professor father and a teacher mother, Ms Truss came from a Labour-leaning family.

During her younger years, she joined her parents on anti-Thatcher demonstrations and as a teenager progressed to the Liberal Democrats' youth and student wing, frequently taking part in protests.

The family upped sticks to Leeds, where Ms Truss attended the Roundhay comprehensive school before studying philosophy, politics and economics at the University of Oxford.

Ms Truss said her admission to Oxford and rise to political prominence was in spite of her state school education, rather than because of it.

She frequently said her time at a comprehensive school in the 1980s had awakened her politically and claimed that “left-wing” governance had held pupils back.

Ms Truss spent more than a decade working in the private sector, primarily as a management accountant and then as deputy director at the right-wing think tank Reform.

She entered Parliament after winning in the 2010 general election by a comfortable majority of more than 13,000 votes.

During her early days in Parliament, she co-authored the Britannia Unchained book alongside Thatcherite future Cabinet colleagues Mr Kwarteng, Priti Patel and Dominic Raab.

It set out proposals to strip back regulation and encourage innovation, but caused controversy with a claim that British workers were “among the worst idlers in the world”.

When Liz Truss branded Britain’s level of cheese imports ‘a disgrace’

Two years after entering Parliament, Ms Truss was part of the government, appointed as an education minister in the Tory-Liberal Democrat coalition.

But while her fortunes were rising in Westminster, her reputation as a speechmaker faltered.

It was in the environment brief that she gave an often-ridiculed address to the Tory conference where she discussed her left-to-right conversion in a pantomime manner.

Her tone switched to a serious one when decrying the state of play that saw the UK importing two thirds of its cheese. “That is a disgrace,” she insisted, deadpan.

Ms Truss’s star kept rising, however, and she spent a year as justice secretary before heading to the Treasury as chief secretary and then leading the Department for International Trade.

Another political conversion was under way as she shifted from arguing to stay in the EU in the year of the 2016 Brexit referendum to become a strong defender of the decision to leave.

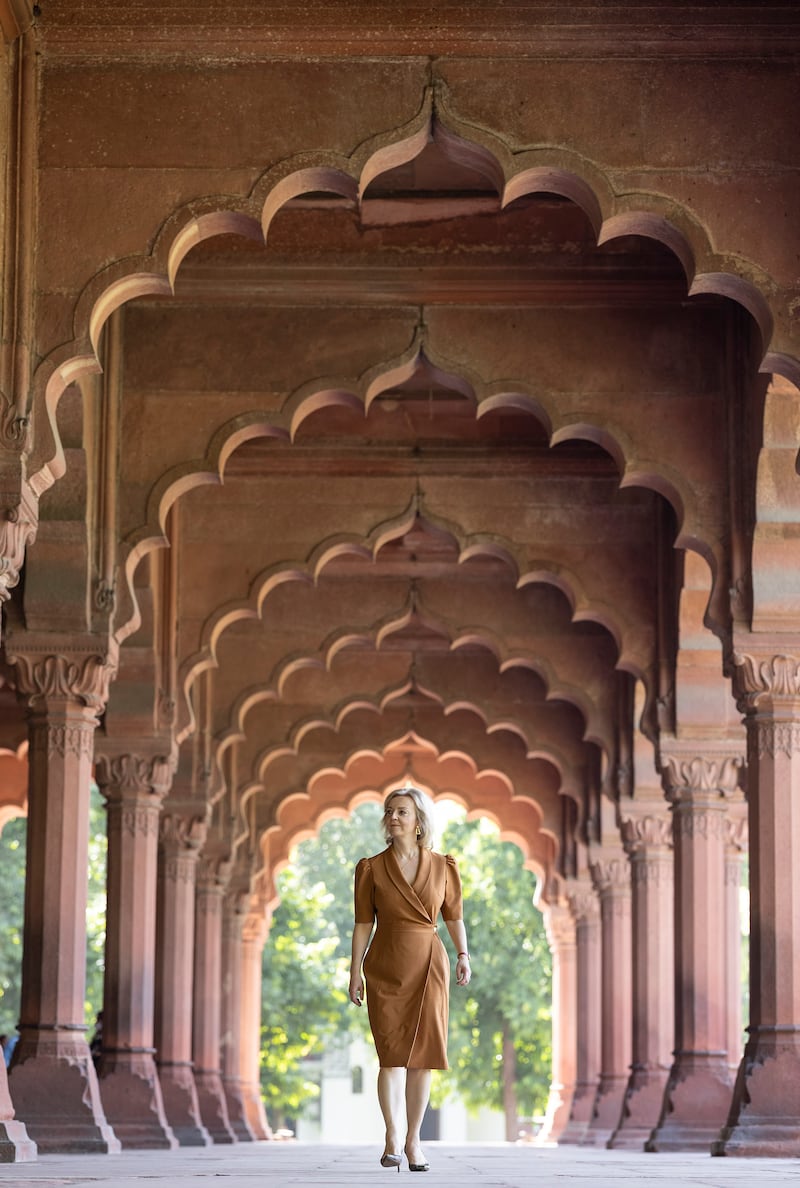

She was eventually rewarded with the role of Foreign Secretary in September last year, becoming only the UK’s second woman to hold the title after Mr Raab was moved aside in the wake of his handling of the Afghanistan crisis.

In the Foreign Office, she took a tough stance in talks and angered the EU with legislation threatening to break international law over the Northern Ireland Protocol.

She also oversaw the successful release of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Anoosheh Ashoori from Iranian detention when other ministers had failed.