CAIRO // A consulate in Libya was stormed by men wielding heavy weaponry, killing the US ambassador and several others. Sporadic violence has erupted in North Sinai, near the border with Israel. A cache of explosives and machineguns belonging to a "terror cell" was found in a Cairo flat.

Taken from the headlines, these recent events seem far-flung and only loosely tied to the greater freedoms coming after the Arab Spring.

But another narrative is emerging that links these worrying signs in an increasingly combustible region: all three events are tied in some way to extreme Islamists who spent years in Egypt's notorious Tora Prison.

After the uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak's regime last year, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf) and later the new president, Mohammed Morsi, presided over an unprecedented amnesty for thousands of Islamist prisoners from Tora and other facilities.

The decision from Scaf to begin releasing Islamist prisoners was never fully explained, but it was clear that many of the men had been held without due process and others had been held for years past the end of their sentence.

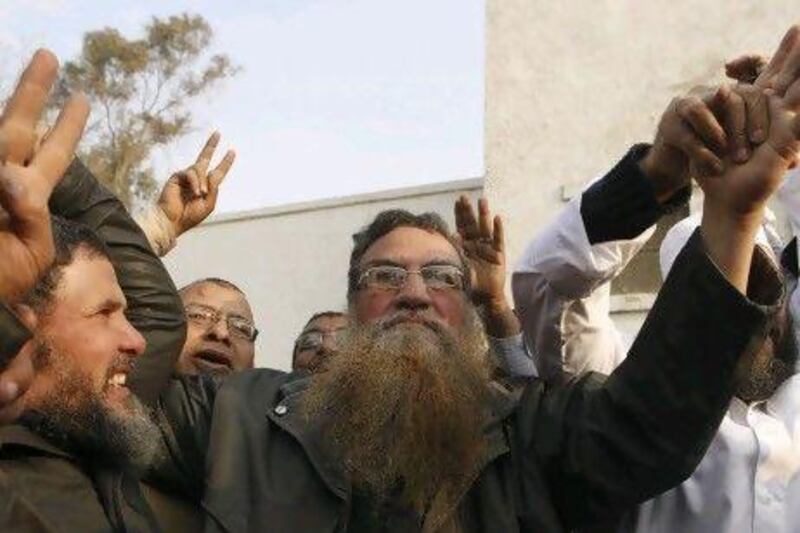

Some of the prisoners had been held since 1981, when Anwar Sadat was assassinated by extremists. Abboud El Zomor is one of them. He was implicated in the assassination and was sentenced to life in prison before his release in March 2011.

Lawyers have successfully appealed for the release of more prisoners, including Mohammed Al Zawahiri, the brother of Al Qaeda chief Ayman Al Zawahiri, and Rifai Taha, who was indicted by the US as a co-conspirator in the attacks on US Embassies in 1998 and is considered a former confidante of Osama bin Laden. Mr Taha said in an interview with the London-based Asharq Awsat newspaper published on September 24th that his group, Gama'a Islamiyya, considered the US "an enemy".

He also appeared to backtrack from what was widely seen as an agreement from leading Islamist groups to renounce of violence in 1996, saying that the Egyptian government did not hold up its end of the deal because it did not release or compensate prisoners.

Asked if the Arab Spring revolutions would have a negative effect on Al Qaeda, he said: "On the contrary, Arab revolutions will provide a better opportunity to move around, but there is no more justification for [Al Qaeda's] existence in many places.

"For example, the Egyptian revolution overthrew the regime and brought a president affiliated to the Islamic Movement. So, why would it operate in Egypt? And the same goes for Tunisia as well."

Some security analysts, such as former FBI investigator Ali Soufan, warned earlier this year of the ramifications of releasing so many alleged extremists into Egypt at a time when the country was still struggling to regain stability.

But Islamist leaders and human-rights lawyers saw their release as a long-awaited day of justice for men who were jailed on flimsy evidence and tortured within a shadowy network of prisons, including Tora.

The view was similar in Libya, where political and Islamist detainees streamed out of the infamous Abu Salim prison in Tripoli after Qaddafi fled to Sirte, where he was eventually killed.

There are, however, growing signs that Mr Soufan's prediction of unintended consequences has some merit.

The attack on the Benghazi consulate has been linked by US officials to fighters who were in contact with a former prisoner of Tora in Egypt, Muhammad Jamal Al Kashef, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal on October 1. Ansar Sharia, a militia suspected of leading the attack on the consulate, counts former detainees of Abu Salim prison among its members.

Egyptian military officials have said that former prisoners of Tora are involved with militant groups in North Sinai, a lawless region in which dozens of bombings and attacks on government offices, gas pipelines and border camps have taken place since last year.

The most dramatic sign of Islamist extremist groups re-emerging came on October 25th, when police clashed with several men holed up in an apartment in the Nasr City section of Cairo. One man blew himself up and eight others were arrested. A cache of weapons was found that included rocket-propelled grenades, automatic weapons and "17 bombs", according to a report in the Al Masry Al Youm newspaper.

Magdi Salem, a former prisoner at Tora who has since worked as a lawyer for Islamists accused of crimes, said that the raid on the apartment was part of a government operation against alleged "terror cells".

The cell in Cairo had been formed two months after Mubarak's resignation, he said.

Among the eight men arrested was Tarek Abu El Azm, a former army officer who had been jailed in 2002 for his connections to an extremist group and was released after Mubarak resigned from office last year.

Tora, a complex of six prisons on the southern edge of Cairo, has long been a dark place to send alleged extremists accused of everything from belonging to a banned group - such as Mr Morsi, a former high-ranking official of the Muslim Brotherhood - to people accused of masterminding attacks on officials in Egypt and abroad.

It was a choice destination for the Central Intelligence Agency to send suspects believed to be involved with extremist groups from around the world, as part of its campaign of "extraordinary renditions".

The signs of violent extremism related to former prisoners of Tora has rekindled a question that historians and scholars of violent Islamist groups have grappled with for years: does imprisonment moderate views of these men or sharpen their fury?

Sayyid Qutb, the Egyptian Islamist thinker whose ideas inspired generations of militants, was radicalised in part by the years he spent in Tora prison where he was tortured in the late 1950s and early 1960s, said John Calvert, the author of a biography of Qutb and professor at Creighton University in the US state of Nebraska.

Ayman Al Zawahiri, too, emerged from Tora in the 1980s with a much more extreme worldview that eventually helped shape the apocalyptic doctrine of Al Qaeda.

But other prisoners at the same time as Qutb did not espouse more violent views after leaving prison, such as the then General Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hasan Al Hudaybi, Mr Calvert said.

After Mubarak's resignation, there appears to be two groups of Islamist extremists. There are those, like Mr El Zomor, who are content to work within the democratic system to push for their goal of an Islamist state. And there are others who "never accepted the revisionism of the leaders" of their groups, Mr Calvert said.

"These individuals see the Arab spring as an opportunity to reignite the jihad, or to at least have an influence on the direction of change," he said. "Not only are the politics of Egypt and other countries in the region in flux, the security situation has not been resolved in favour of the state. ... We may expect such individuals to form or join small, radical jihadi groups or else, act individually."

bhope@thenational.ae