DOHA // When it comes to his opinion of the legal responsibilities that Arab governments have towards their citizens, Karim Khan does not mince words.

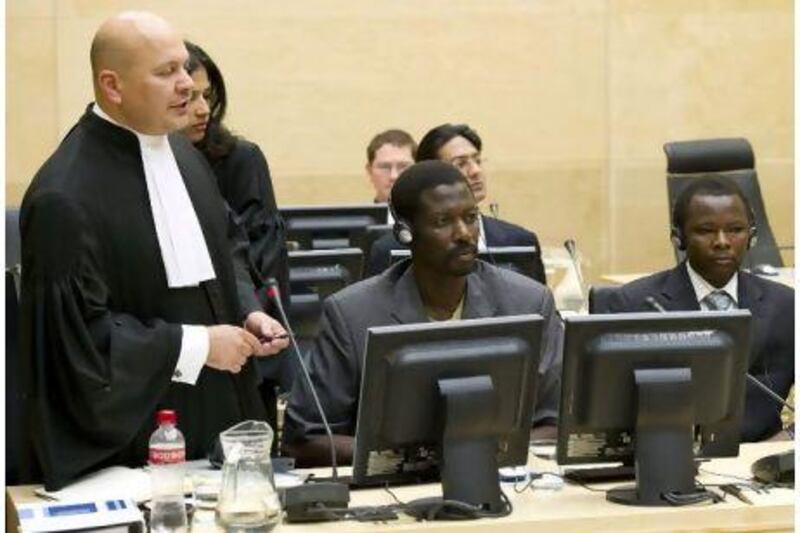

"The buying of arms and having a fantastic military doesn't secure rights," the defence counsel for the International Criminal Court told Arab leaders gathered here yesterday. "Justice has to be attained differently."

For two days in Doha this week, Mr Khan and top lawyers and officials for the ICC spoke articulately about the need for greater Arab representation in the world's first-ever permanent tribunal for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The response of the audience to Mr Khan's impassioned appeal was typical. Uncomfortable smiles were exchanged, followed by shrugs and silence.

At the root of the audience's distinct lack of enthusiasm was the question: What's in it for Arab governments? And more importantly, what was the ICC doing to address the perception that the court and other instruments of international justice favour the powerful over the weak, the rich over the poor and Israel over almost every other nation?

In more than a dozen interviews, legal experts, scholars and government officials from Arab states expressed reservations with the court's mandate, scope and impartiality. Only three Arab states have signed and ratified the Rome Statute of 1998, the court's founding treaty - Jordan, Djibouti and Comoros.

Ghassan Moukheiber, a Lebanese parliamentarian and chairman of the Arab Region Parliamentarians Against Corruption, said there are a number of changes the court must make before it gains credibility and acceptance in the Arab world.

The first is for the United States, China, Israel and other influential states to accept the jurisdiction of the court. Without this, broad Arab support for the court is unlikely to be forthcoming any time soon.

The United States and Israel, in particular, have refused to enlist in the court, worrying that their government officials and military personnel would be subjected to politically motivated prosecutions. Washington also has argued that the US judicial system is already capable of carrying out war-crimes prosecutions of American citizens in a fair and impartial fashion.

These arguments carry little weight in Arab capitals, Mr Moukheiber said.

"The attitude of many Arab countries is, 'Why do I ratify if Israel hasn't ratified?", he said. "Why do I ratify if the US hasn't ratified?' [Arab States] are putting it as a quid pro quo - I'll wait for Israel."

Andrew Cayley, a former senior attorney with the ICC, suggested this view, while somewhat justified, may be short-sighted.

He said Arab leaders should consider what a unified legal front on Israel's borders might do to upset the current legal balance. The more Arab state members, the thinking goes, the more pressure on Israel.

The other approach would be to obtain statehood for Palestine, something the UN is to consider in September. Member states can refer cases to the court unilaterally, and the Palestinian territories, at least by the court's definition, does not meet the criteria of a state.

Whatever the merits of these suggestions, at the end of the day the perception here was that the court needs an overhaul, not the Arab world's relationship with it.

Though few would acknowledge publicly, in private, legal scholars say the problem is less the policies of Arab governments and more what they allege is the prosecutorial bias at The Hague-based court. There is a belief, and not just in the Arab world, that the ICC's image can only be repaired when its current prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, steps down next year.

In an interview with The National earlier this month, Mr Moreno-Ocampo, who was not in attendance in Doha, defended his approach of going after top leaders even at the expense of a more time-consuming method of lower-level players and working up.

Whatever its merits, however, Mr Moreno-Ocampo's modus operandi has reinforced a perception among Arab leaders that vengeance, not justice, is the motive for the court's prosecutions, observed Namira Negm, a professor of legal studies at the American University in Cairo. There is a reluctance among these leaders, she said, to support a legal framework that could be turned against them.

Against the background of the regional perceptions, it may be decades before a majority of the nations of the Middle East and North Africa sign on to the court. It is difficult to see Syria or Yemen, at least in the near-term, becoming a party. The best the court may hope for is to encourage reforms internally, so that Arab states build the legal systems that are able to try war crimes domestically.

The prospect of a long struggle for support did not deter ICC from toiling this week to enlist more Arab voices.

"You may be wondering, why should my country join the ICC?", the court president, Judge Sang-Hyun Song, asked delegates from around the region, including Bahrain, Kuwait and Iran.

Answering his own question, Judge Song said it was to gain the protection and services of the court, send a signal about commitments to rule of law and peace, and help build a "truly global court."

For all the reservations about the court that were in evidence here in Doha, attitudes are not etched in stone.

Since the beginning of the Arab Spring, Tunisia and Egypt have announced their intent to consider ratifying the Rome Statute. Mahmoud Samy, Egypt's ambassador to the Netherlands, where the ICC is located, said: "There is a growing interest in supporting human rights and joining old treaties that are giving more human rights to the people." These treaties include the ICC, he said.

Qatar is also looking to bolster its credentials as a regional reformer. Along with the UAE, this tiny nation has provided resources to help depose Colonel Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. The country is also cooperating with the UN to establish a regional anti-corruption charter.

That Qatar hosted the ICC at all was a bold statement. In 1998, Qatar was one of seven states to vote against the Rome Statute (including China, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, the United States and Israel). Two years ago, Qatar openly rebuffed the ICC when the accused war criminal and Sudanese president Omar al Bashir flew to Doha for an Arab League summit days after a warrant was issued for his arrest.