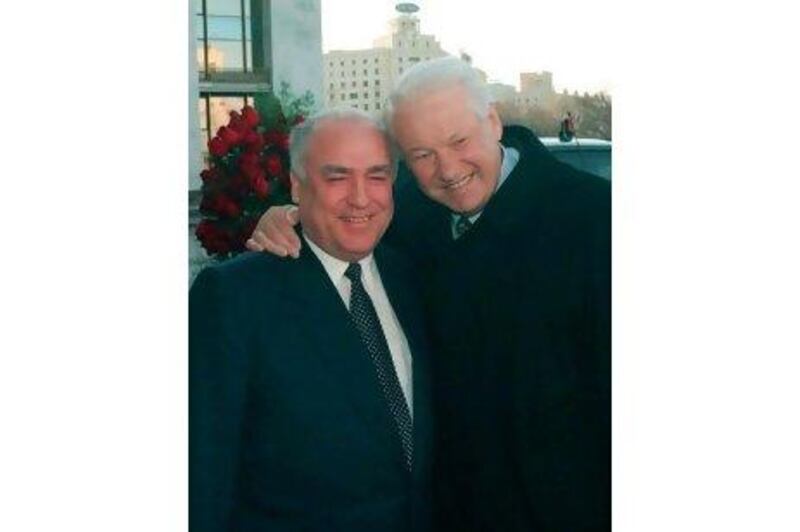

Viktor Stepanovich Chernomyrdin was one of the key politicians active in the Kremlin as Russia moved away from communism towards a market economy in the turbulent 1990s.

He served the president, Boris Yeltsin, as aide and then as prime minister from 1993 to 1998, helping push through liberal reforms and overseeing the strengthening of the ruble. He negotiated major loans from the International Monetary Fund that would ultimately push Russia's economy clear of post-Soviet turmoil.

His critics decried his reforms as inconsistent and claimed that the economic innovations had come at too great a cost to Russia's industry. One colleague commented that his conversion to the cause of market reform was "the most expensive education in history".

In 1995, he angered Kremlin hardliners by negotiating with Chechen guerrillas to end a hostage crisis in the southern city of Budyonnovsk as the international media hung on his every word. The following year, he held the reins of power - and control of the country's nuclear codes - for 23 hours while Yeltsin underwent heart surgery.

His greatest achievement was the creation of the world's largest gas corporation, Gazprom, which holds 17 per cent of Earth's natural gas reserves, and serves as the Kremlin's most powerful economic tool on the international stage. "My whole life went by in an atmosphere of oil and gas," he once said.

Sacked for alleged economic incompetence early in 1998, he was recalled by Yeltsin, but the State Duma rejected his candidature. Soon afterwards, he announced his intention to stand in the 2000 presidential poll, despite a marked lack of support. Instead, for eight years, from 2001 to 2009, he acted as the country's ambassador to Ukraine, an appointment widely believed to be an attempt by Vladimir Putin, Yeltsin's successor as president, to distance him from the centre of Russian politics.

In February last year, he strained relations between Russia and Ukraine by declaring in an interview: "It is impossible to come to an agreement on anything with the Ukrainian leadership." Soon after he was relieved of his duties by Dmitry Medvedev and subsequently appointed presidential adviser and special presidential representative on economic co-operation with member countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States, which was formed from the remnants of the Soviet Union.

One of five children born to a peasant family in Siberia, Chernomyrdin left school in 1957 and went to work as a mechanic in an oil refinery. There he remained until 1962, with a two-year hiatus while he completed compulsory military service. In 1966, he graduated from the Kuybyshev Industrial Institute, and went to work in the Soviet Union's booming gas industry. In 1972 he completed further studies, by correspondence, at the department of economics.

He worked his way steadily up the Soviet industrial ladder. In 1982, he was named deputy minister of the federal natural gas industries. From 1985, he served as the minister of gas industries and in 1989 was elected chairman of the oil and gas ministry.

As head, he anticipated the importance of the market as the Soviet Union crumbled and in 1989 merged the most lucrative gas assets into a new monopoly, Gazprom. Months after Yeltsin appointed him prime minister in 1992, he signed a decree turning Gazprom into a joint stock company.

In Russian-speaking countries, he was famous for his numerous malapropisms and ungrammatical speech. He once told opponents: "If your hands are itchy, scratch yourself on other spots." Of his many expressions, the most frequently quoted was: "We wanted the best, but it turned out as always." Uttered after a spectacularly unsuccessful monetary reform by the Russian Central Bank in July 1993, it became a popular proverb, encapsulating for a generation of Russians the corruption-riddled failure of the transition from communism to a market economy.

His wife predeceased him. He is survived by their two sons.

Born April 9, 1938. Died November 3, 2010.