ISTANBUL // Five years after it started membership talks with the European Union, Turkey is becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow progress of negotiations and has started to disconnect its programme of democratic reforms from the EU's script, observers and politicians say.

"If you do not want Turkey, then come out and say it," Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the prime minister, said during a speech at a business conference in Istanbul this week, addressing the EU. "Don't keep us at arm's length."

Accepted as a candidate country by the EU in 1999, Turkey started formal accession talks in October 2005, but negotiations have proceeded very slowly. So far, Ankara has been able to address not even half of the 35 negotiation chapters ranging from human rights to food safety standards that a candidate country needs to comply with in order to become a member. Several chapters are blocked because of a row over Cyprus, others have been held up by EU member France, which is openly opposed to the accession of the overwhelmingly Muslim country of 70 million people.

Turkey first applied to become a member in the club of European democracies in 1963, and the project has traditionally enjoyed broad public support as it exemplifies the country's move towards western liberal standards. But the lack of progress in recent years has taken its toll. According to a poll published last month, only 38 per cent of Turks still support the aim of membership. Members of Mr Erdogan's government have been expressing their frustration about what they see as a concerted effort by Turkey's critics in the EU to stop the country's march towards membership. "No other candidate country has seen 18 chapters blocked for political reasons," Egemen Bagis, Turkey's EU minister and Ankara's top negotiator in the accession talks with Brussels, said during a panel discussion on Turkey's EU accession process in Istanbul last week.

Ankara is also angry about the EU's decision to lift visa restrictions with several Balkan states that have not even begun membership talks while refusing to do so in the case of Turkey. "We want this visa nonsense to end," Mr Bagis said. EU officials say that membership talks have been difficult for other countries as well but that a disagreement over ports makes things even more complicated in Turkey's case. "It remains difficult, uncertain and frustrating," Marc Pierini, the EU ambassador to Turkey, told the panel with Mr Bagis.

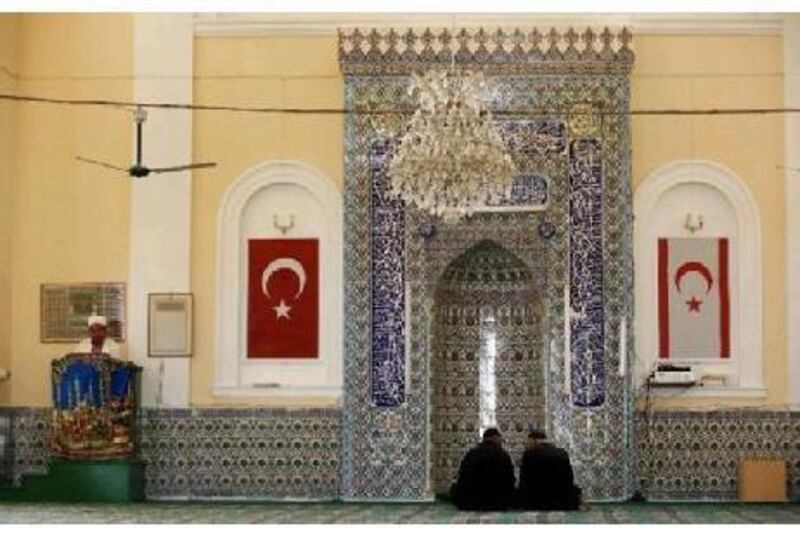

The EU has told Turkey to open its ports for ships from the Greek republic of Cyprus, which has been an EU member since 2004, before eight negotiation chapters currently on hold can be unblocked. Ankara says it is willing to fulfil that demand only if the EU makes good on its promise to end the economic isolation of the Turkish sector of Cyprus by accepting direct trade between EU countries and the Turkish Cypriots. But a direct trade regulation designed by EU officials has been blocked by Cyprus.

Turkish diplomats say the negotiation process may come to a complete standstill by the end of the year if the Cyprus problem is not overcome. Mr Pierini, the EU ambassador, said there may be a "transitional solution", although he did not provide details to such a solution. Despite all the problems of the accession talks and even though its prospects of joining the EU any time soon are slim, Turkey has embarked on a new wave of liberal reforms. Last month, voters passed an unprecedented package of 26 constitutional amendments, designed to further weaken the political power of the military while strengthening civil rights, in a referendum.

Cengiz Aktar, a political scientist and EU specialist at Istanbul's Bahcesehir University, sees the current set of changes as a "second wave of reforms" after a first phase that lasted from 2002 to 2005. The main difference between the two reform periods is that the current one is no longer exclusively powered by the desire to fulfil the wishes of the EU, but by interests and calculations independent of the EU process, he said.

"These reforms have not been made under the order of the EU," Prof Aktar told the panel in Istanbul, in reference to changes made since late 2008. "For the first time, there is a domestic dynamism." He pointed out that Mr Erdogan, in his victory speech after the acceptance of the constitutional reform package in the referendum on September 12, had not mentioned Europe at all. "He talked about everything, but not about the EU."

One factor behind the domestic reform drive is a civil society that has been strengthened by democratic changes in recent years. But the government itself is also interested in reforms that can help to solve long-running political problems such as the Kurdish conflict and can boost Turkey's economic power. "We have become the sixth largest economy in Europe without receiving any EU money," Mr Bagis, the EU minister, said.