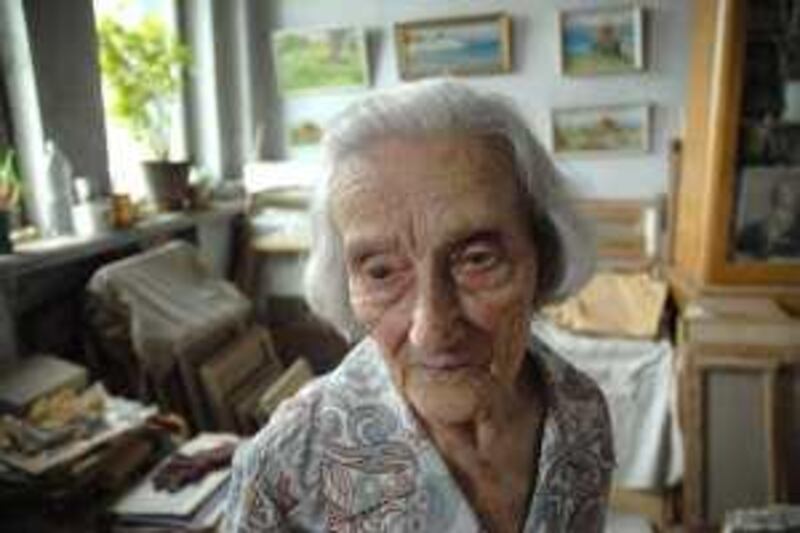

YEREVAN, ARMENIA // Yelena Abrahamyan is one of the dwindling number of survivors of what Armenia describes as the genocide against its people nearly a century ago. Now 97, the artist admits she is concerned her country could establish relations with neighbouring Turkey, which rejects Armenia's assertion that 1.5 million people died when the Ottoman authorities drove them from what was then Western Armenia. Turkey, which shut its border with Armenia in the early 1990s in a dispute over the breakaway Nagorno-Karabakh territory, officially part of Azerbaijan, claims the death toll was 300,000. The two countries have held talks over establishing diplomatic relations, which Armenia has said it is prepared to do without Turkey's acceptance that "genocide" took place.

Any border reopening would be expected to lift Armenia's stuttering economy, but Ms Abrahamyan believes the genocide issue should take precedence. "Until they recognise the genocide, they shouldn't open the border," she said. "I don't think they will recognise it any time." Her cousin, the daughter of her aunt, was among those who died during the events that Ms Abrahamyan says she remembers "very well". After moving to present-day Armenia in 1920, Ms Abrahamyan went on to become a distinguished artist during the Soviet era. She was part of a group of artists who moved into an apartment block in the centre of Yerevan when it was completed in 1951.

In an arrangement common at the time, the accommodation was provided by the local artists' union and as many as 28 artists lived in or had studios in the block, where Ms Abrahamyan still lives. Sometimes painters had to produce work that reflected the communist policies of the times, and Ms Abrahamyan was no exception. Holding a black-and-white leaflet about her paintings, with text in Russian, she pointed at a 1961 portrait of a woman in a farmyard setting. "This was a woman who works on a collective farm," she said. "She is not an interesting woman, you can see. It is nothing as a portrait but I was made to do it. Everybody was made to paint the villages and collective workers." But not all of her pictures had a socialist agenda: her walls showcase vibrant and colourful paintings of coastal scenery, churches and countryside.

In her spare room canvases are stacked up by the dozen, and a white metal pot on her sideboard contains brushes of different sizes. Ms Abrahamyan is the only artist left in the apartment block, which overlooks Yerevan's opera house, whose many hoardings for forthcoming productions are testament to the continued thriving of the city's artistic scene. While the other artists have died, about 80 per cent of the flats are occupied by their descendants, according to Anahit Stepanyan, also a resident of the block and herself a painter's daughter. "Later on, there were a few other buildings for painters, but this was probably the first one," she said.

"Nearly all the painters living here were famous and most of them were teaching in the art academy or art colleges." Ms Stepanyan's father, Suren Stepanyan, was born in 1915 to parents who came from what was then Western Armenia. Like Ms Abrahamyan, he moved into the building in 1951 and was based there until his death in 1977, when his flat passed to his family. More than two dozen of his paintings, ranging from early realist pictures to more abstract designs, are displayed in his daughter's flat. Many foreign travellers to Yerevan get the chance to enjoy the paintings as, like some other residents of the block, Ms Stepanyan runs a homestay. As well as painting in oil and other media, Stepanyan produced wood carvings and metalwork, including a medallion presented to the Soviet former chess world champion Tigran Petrosyan. He also illustrated magazines and books written by some renowned Armenian writers. "He got a lot of orders for these things," Ms Stepanyan said. "They were all government [magazines] but they were very good. "There was huge support for the sciences, culture and education. The people didn't have to think about earning money, they were just creating." Her sister Gayane said their father was fortunate in that he rarely had to produce art that could be described as propaganda. "My father didn't do such things because he was too high," she said. "He was very talented and he was very free." According to Vardan Azatyan, an art historian at Yerevan State Academy of Fine Arts, it was also "quite common" for the state to provide buildings for composers and writers. He said artists suffered "harsh and strict controls" under Joseph Stalin, who died in 1953, but the situation eased under his successor, Nikita Khrushchev. "It's a very common feeling, especially in Armenia, that the Soviet-era artists, they think they were forced to do something against their will," he said. This "rejectionism" of socialist realism, as Mr Azatyan describes the feelings that Ms Abrahamyan and others have towards some of the work of the time, means such art is rarely exhibited in Armenia. "In the National Gallery of Armenia, there's no exposition of the works of socialist realism," he said. "But it's a kind of art and it's a period of history that this and other Soviet countries went through." dbardsley@thenational.ae