Local authorities in the city of Bayan Nur in the Chinese region of Inner Mongolia issued a warning on Sunday after a hospital reported a case of suspected bubonic plague. It followed four reports of plague in people there last November, including two of pneumonic plague, a deadlier variant.

The internet sprung to life with dire predictions of a second pandemic and historical references to the Black Death, which is believed to have killed a third of Europeans between 1347 and 1351 – at least 25 million people.

The threat today is very different. Here’s what you need to know.

What is the bubonic plague?

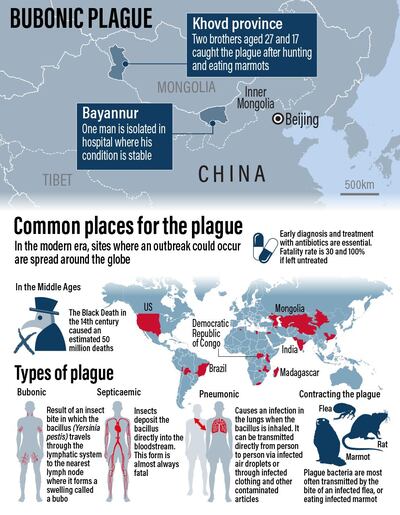

Bubonic plague, also known Plague bacillus or Yersinia pestis, attacks the lymph nodes, leading to swelling, pain and pus formation.

Although related, it differs from septicaemic plague (which if it enters the bloodstream can cause meningitis and endotoxic shock) and pneumonic plague, which produces severe pneumonia.

Without prompt and effective treatment, 50 to 60 per cent of cases of bubonic plague are fatal, the World Health Organisation says. But the disease is entirely treatable – more on that below.

Didn’t it die out years ago?

Mostly, but cases do still occur. The US has averaged seven cases per year for the past few decades, says the US Centres for Disease Control, and Madagascar and other nations have experienced a low number of cases in recent years.

Cases have also occurred in Inner Mongolia before, so it seems the current coronavirus pandemic is stoking fear of other diseases.

“Because plague is a disease of wildlife, it is very difficult to eliminate it completely,” said Jimmy Whitworth, Professor of International Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

How can humans contract it?

The disease is usually spread via fleas living on rodents – the majority of US cases of human infection came from marmots and prairie dogs – but can also be contracted through contact with contaminated fluid or tissue of an animal that died from the disease.

Humans can spread the disease between one another by infectious droplets, but it requires the infected person to be in very close contact and have a case of plague pneumonia.

The CDC said this type of spread has not been documented in the US since 1924, but still occurs with some frequency in developing countries.

Is it preventable or treatable?

Yes to both. For those regularly exposed to the disease, there is a vaccine, although it is not widely available. It can be treated with simple antibiotics.

“It is good that this has been picked up and reported at an early stage because it can be isolated, treated and spread prevented,” said Dr Matthew Dryden, a consultant microbiologist at Hampshire Hospital NHS Trust in the UK.

“Bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium and so unlike Covid-19 is readily treated with antibiotics.”

Should we be worried about the case in Mongolia?

“Bubonic plague is a thoroughly unpleasant disease and this case will be of concern locally within Inner Mongolia,” said Dr Michael Head, Senior Research Fellow in Global Health at the University of Southampton in the UK.

“However, it is not going to become a global threat like we have seen with Covid-19. Bubonic plague is transmitted via the bite of infected fleas, and human-to-human transmission is very rare.”

The WHO said the case is being managed well.

“We are monitoring the outbreaks in China, we are watching that closely and in partnership with the Chinese authorities and Mongolian authorities,” WHO spokeswoman Margaret Harris said at a UN press briefing in Geneva.

“At the moment we are not … considering it high-risk but we are watching it, monitoring it carefully,” she said.

Coronavirus: What is a pandemic?