SRINAGAR, India // Anger and protests over the execution of a Kashmiri man convicted in a deadly attack on India's Parliament have stirred fears the volatile Himalayan region could again descend into a cycle of violence after two years of relative peace.

Kashmir has been rocked by anti-India protests, despite a rigid curfew, since Mohammed Afzal Guru was hanged in New Delhi early on Saturday. Three protesters have died so far in clashes with security forces.

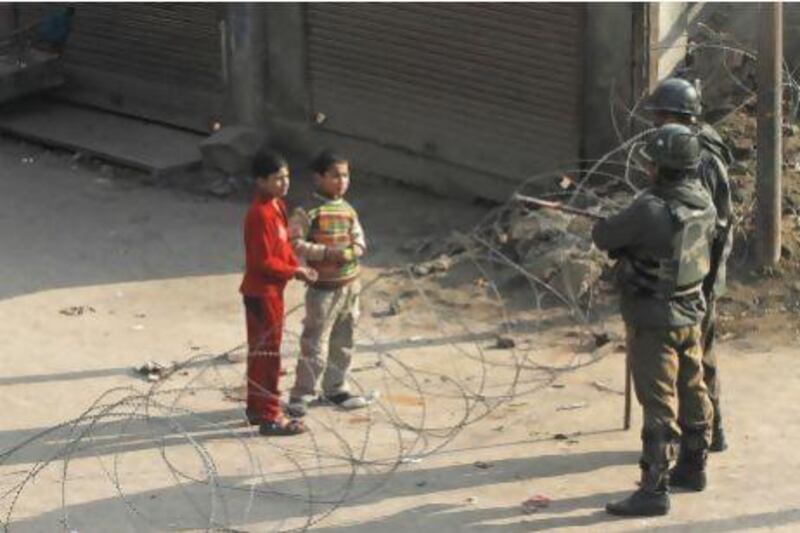

Tens of thousands of troops patrolled the streets of Indian-controlled Kashmir yesterday, confining residents to their homes.

Shops, businesses and government offices were closed, streets ringed with barbed wire were deserted, and the region's nearly 60 newspapers were unable to publish for a third day. Cable television and mobile internet services were shut down in most areas.

Violent clashes and rigid curfews were long routine in Indian-held Kashmir, where insurgents have been fighting for more than two decades, demanding either a separate state or merger with Muslim-majority Pakistan. The region is divided between India and Pakistan and claimed in its entirety by both.

However, a slew of measures ranging from a harsh security crackdown to the government's use of sports, economic development and culture to promote goodwill toward India have helped authorities maintain relative calm in Kashmir over the past two years. During that time, the region received a record number of tourists.

But the region remains a tinderbox, and many fear Guru's execution could be the match that lights it. Many Kashmiris believe Guru did not get a fair trial, and the government's surprise execution of the man - with his family only finding out afterward - only exacerbated the anger here.

"Please understand that there is more than one generation of Kashmiris that has come to see themselves as victims, that has come to see themselves as a category of people who will not receive justice," Omar Abdullah, Indian Kashmir's top elected official, told reporters.

"Whether you like it or not, the execution of Afzal Guru has reinforced that point that there is no justice for them, and that, to my mind, is far more disturbing and worrying than the short-term implications for the security front," he said.

Separatist politicians called for a mass funeral prayer for Guru to be held on Friday at a large square near Srinagar's Martyr's Graveyard, where hundreds of separatists and civilians killed in the conflict are buried.

"This hanging has magnified manifold the sense of alienation and dejection and has plunged Kashmir into new cycle of uncertainty," said Sheikh Showkat Hussain, an international law professor at Central University of Kashmir. "This has also closed the doors of any reconciliation for those who wanted to be a bit moderate toward India."

Unknown residents have, meanwhile, put up a tombstone as a mark over an empty grave for Guru in the main martyr's graveyard in Srinagar. The epitaph reads: "His mortal remains are lying in trust with the government of India. Kashmiri nation awaits its return."

Since 1989, an armed uprising in the region and an ensuing crackdown have killed an estimated 68,000 people, mostly civilians. But in recent years, as the uprising waned, Kashmiris took a different tack, taking to the streets to protest, often in response to an event that triggered anger across the region.

In 2010 alone, 112 people were killed as troops fired live ammunition into the crowds, inciting further protests in a deadly cycle of violence.