RABAT // When she was 12, and against her parents' orders, Salma Bounjara went into their bedroom and slid volume one of a novel from the bookcase: The Thorn Birds, a story of romance in the Australian outback. "You're too young for that kind of book," her mother told her when Bounjara confessed. But she handed over the missing second volume, resigned to her daughter's drive to find things out.

Today that drive fuels the quest of Bounjara, a 21-year-old journalism student in Rabat, the Moroccan capital, to become an investigative reporter, one of many young journalists seeking careers among new media testing social taboos and government restrictions. "Morocco is virgin territory," she said. "Right now, you open up most of the papers and they're just empty." She was dismayed last month when the government shuttered Le Journal Hebdomadaire, an independent magazine known for reporting critically on the state, citing unpaid taxes in a move the magazine's founder claimed was nonetheless politically motivated.

Media rights watchdogs have said that Moroccan authorities are allegedly using courts to silence critics. Despite the risks, Bounjara sees the country's growing media industry as a place where she can flourish. That industry took shape under 20th-century French colonialism, when many newspapers were written by and for foreigners, among them L'Écho du Maroc and Le Petit Marocain. Not to be outdone, in the 1930s Moroccan nationalists offered competition with titles including L'Action du Peuple and Al Salam. Independence in 1956 brought state media and party organs such as the leftist Libération and the establishment L'Opinion.

It also brought the four-decade reign of King Hassan II, who shuttered papers that challenged him and jailed dissidents during a period remembered as les années de plomb - the years of lead. When the late king Hassan eased restrictions in the late 1990s, a young business school graduate named Aboubakr Jamai saw an opening for a new kind of reporting. "We wanted to set up a profitable operation while maintaining a decent editorial line and living up to ethical standards of good journalism," said Jamai, who co-launched Le Journal after legislative elections in 1997 strengthened party politics by bringing the opposition into government. "We are the offspring of the dream that Morocco was opening up."

Le Journal investigated the murky intersection between politics and big business, while Jamai's editorials repeatedly challenged government policies. However, that set off a string of lawsuits, closures and fines that saw him relaunch the publication as Le Journal Hebdomadaire and leave Morocco when his assets were seized in 2007. Last month a court liquidated the magazine's holding company and despatched bailiffs to replace locks at its Casablanca office, citing mountains of unpaid tax.

Jamai acknowledged the debts but claimed authorities had encouraged advertisers to boycott Le Journal Hebdomadaire in retaliation for his criticism of the state, starving the magazine of revenue. The communication minister, Khalid Naciri, said the magazine's closing was not politically motivated. "We don't forbid anyone to criticise, but a professional journalist is one who respects the law." The government has called legal actions against media in recent years a legitimate response to allegedly inaccurate journalism.

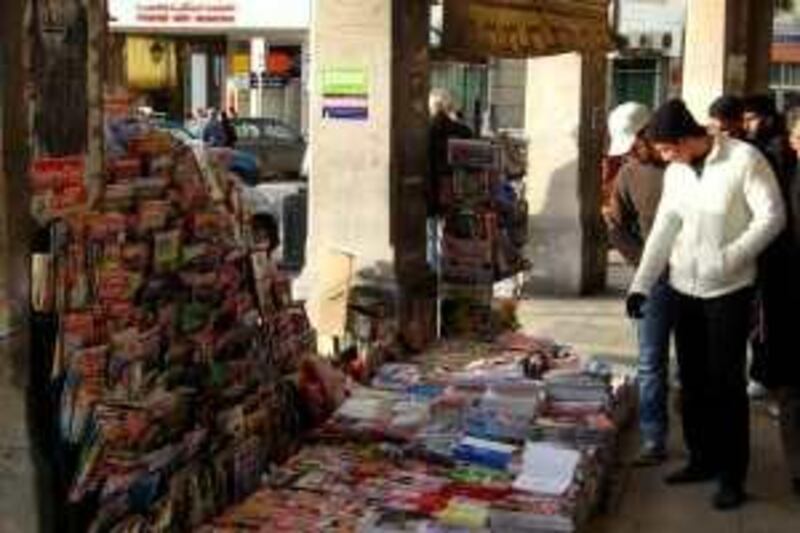

Authorities crack down on journalists accused of libel or breaching restrictions on criticising Islam, the monarchy and Morocco's rule in Western Sahara, a trend that accelerated in 2009, according to a report last month by Human Rights Watch. Nevertheless, media have proliferated as limits have relaxed overall during the past decade. News-stands are crowded with new titles, from the Islamist Al Tajdeed (editorials condemning alcohol and mixed bathing), to the liberal TelQuel (critical reporting on government and society), to the popular daily Al Massae (a mix of hard news and scandal).

In 2006, the airwaves were opened to private broadcasters including Luxe Radio, launching next month, where a reform-minded reporter, Ikram el Ghinaoui, 28, has found a new home. In April 2007, el Ghinaoui risked death while covering Casablanca suicide bombers for a different station. "I was thrown to the ground and burnt a bit, and when I got up to do a 'live' my voice was trembling," she recalled. "Afterwards male colleagues said I had been rattled because I'm a woman."

It was a catalysing moment. "I want to change that kind of mentality," el Ghinaoui said. "Journalism is the best way to make Morocco advance." Starting next month, she will host a daily one-hour programme profiling prominent women. Bounjara, meanwhile, will finish her journalism studies in June. She has freelanced for newspapers on culture and society but hopes to start covering politics. "I want to see a lot more investigative journalism, especially about public money," she said. "That's the big question worrying everyone: where is the people's money going?"

Jamai is not planning a comeback. But he hopes young journalists like Bounjara and el Ghinaoui will continue braving the choppy seas in which Le Journal Hebdomadaire ultimately foundered. "I believe in markets, I really do," he said. "My experience in Morocco showed me that when markets are left alone, there is space for daring, serious journalism." jthorne@thenational.ae