Anyone with an email address has been there. An unsolicited offer out of Africa, promising a fortune. All the sender needs is a helping hand to retrieve millions hidden in a secret overseas account.

“Please, sir/madam, send your bank details as a matter of urgency.”

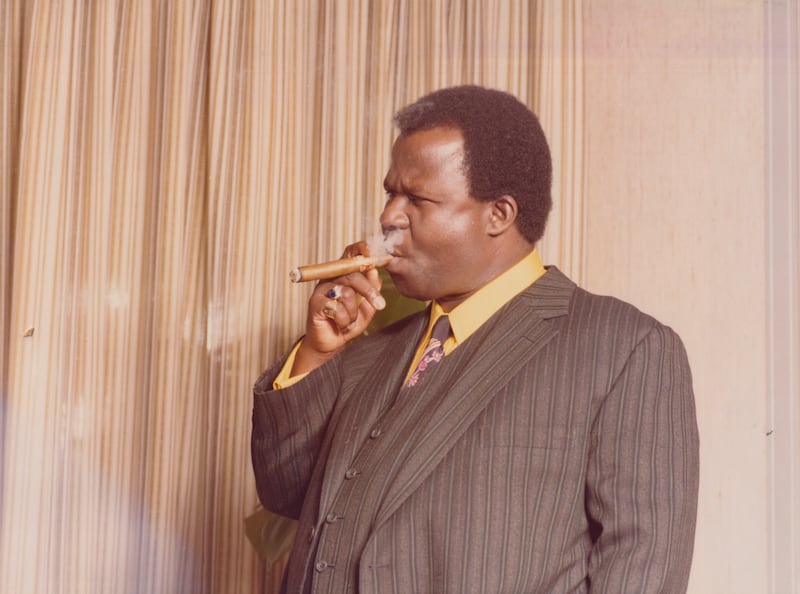

Except this particular fraud – because it always is a fraud – dates back decades before the internet and was carried out by John Ackah Blay-Miezah, a Ghanaian con man of spectacular proportions.

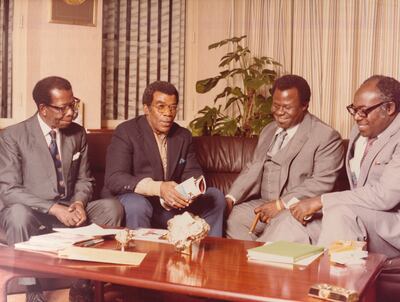

For years, he persuaded the gullible (mostly rich Americans) that he had been entrusted with the secrets of tens of millions in gold bars hidden in Switzerland by Ghana’s former president, Kwame Nkrumah.

Only Blay-Miezah knew the location, and only Blay-Miezah could access it. But it wouldn’t be easy, he warned. There were legal and diplomatic complications that would need time and money, a lot of money, to resolve.

And so the Oman Ghana Trust Fund was born; sole beneficiary, as it turns out, John Ackah Blay-Miezah.

The full, audacious, story is told in a new book, Anansi’s Gold, by the Ghanaian writer and journalist, Yepoka Yeebo. Anansi is a folk hero from West Africa, a god in spider form who endlessly outsmarts his opponents using cunning and wit.

The story of this modern Anansi will be a revelation to most us. Outside Ghana, Blay-Miezah is almost unknown. He does not even have that ultimate recognition of fame or infamy: a Wikipedia page.

During the 1970s and '80s, though, Blay-Miezah extracted several hundred million US dollars from investors. No one, it seems, doubted his story, or found him anything other than charming.

“I don't think I encountered one person who was originally involved or gave money over who didn't think that the money existed and didn't think of Blay-Meizah somewhat fondly,” Yeebo tells The National.

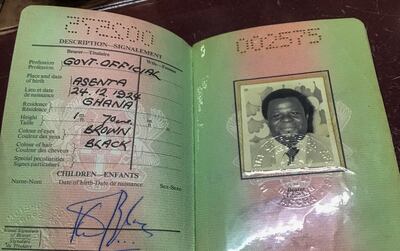

Blay-Meizah was born in 1941, in rural Ghana. By all accounts, he was a charmer even as a child. An altar boy, everyone was pleased when he claimed to have won a scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania in the US in 1959.

It was his first lie. While Blay might have partied with other African students, in reality he was working as a bus-boy at a private members club, washing dishes and clearing tables. He was fired after a year.

By the early 1970s, he was back in Philadelphia posing as a Ghanaian diplomat, running up huge bills he had no intention of paying in fancy hotels. Arrested and charged with fraud, he was given a one- to two-year prison sentence, still claiming diplomatic status. A prison psychiatrist noted: “I feel this man cannot distinguish reality from fantasy.”

But the small-time con man was about to hit the big time. Back in Ghana, Blay-Meizah began to spin his story. It centred on Kwame Nkrumah, who had led his country to independence from Britain in 1957, but was deposed by a military coup nine years later.

Before his death in 1973, he had confided a secret to his good friend Blay-Meizah. Hundreds of gold bars representing Ghana’s wealth had been deposited in Switzerland as the Oman Ghana Trust Fund, to be repatriated one day to restore the country’s fortunes. And only he, Blay-Meizah, could get it out.

There is no evidence Blay-Meizah ever met Nkrumah beyond a brief handshake during a campaign trip. But the story rang true to many of his countrymen. After all, the British had exploited Ghana’s considerable mineral resources for years, and it was rumoured, wrongly, that a large portion of this had been set aside for the country’s future.

Armed with the story, Blay-Meizah set about recruiting investors to retrieve the gold and who would receive massive returns on their investment. By one account, he extracted more than US$200 million from American investors alone before he was finally exposed in the early ‘90s. He died in Ghana, under house arrest, in 1993.

Blay-Meizah maintained his story until the end. In the late '80s he was investigated by Ed Bradley of the CBC programme 60 Minutes. Interviewed in London, wearing traditional robes, Blay-Meizah first insisted on a “tribal ritual” of swallowing a mouthful of gin and then spitting it on a golden “ceremonial sword”.

This, he said, required him to speak the truth. Sitting on his tribal “throne” (in reality a reproduction Louis XV chair) he was asked directly by Bradley: “Have you defrauded people?” He answered: “I have not.”

Yeebo first learnt of Blay-Meizah more than two decades after his death, and in that most modern of ways; a WhatsApp from her mother in 2016 that included a clip from 60 Minutes.

“That’s when I started poking around,” she says. “Initially, I was like: ‘This is obviously a scam.’ But my mum was saying: ‘Is it true? Do you think what he’s saying is true?’ And she’s a pretty serious person, a doctor.

“For the next weeks, I would tell friends about it. And everybody had a story that was similar. And a good number of the people I spoke to were like: 'It's possible that what he is saying is true and it's also possible that he's a huckster.' ”

Yeebo’s point is that Blay-Meizah is unusual only in the sense of the scale of his fraud. Con men like him have been around for centuries. Often, there is just enough of a grain of truth in their stories to hook even the most cautious.

She spent the next six years diving ever deeper into the rabbit hole as she researched the book. “It was countless newspapers, countless clips, countless personal archives, just endless document requests.”

Many of those who had known Blay-Meizah were nearing the end of their lives, a race against time that Yeebo sometimes lost.

Some surprising names cropped up. The US ambassador to Ghana who became wary of Blay-Meizah in the 1970s was none other than Shirley Temple Black, the former child star of films such as Wee Willie Winkie and Bright Eyes in which she sang On the Good Ship Lollipop.

Henry Kissinger, former US Secretary of State under Richard Nixon, is reported to have been baffled by him. John Mitchell, Nixon’s attorney general and architect of the Watergate break-in, flew to Ghana to offer his services as a legal adviser. Blay-Miezah even spent time with W.E.B. du Bois, the celebrated black academic and civil rights activist.

In Ghana, he is remembered more fondly. Some of his millions were handed out to launch a short-lived campaign for the presidency. More went to a lower league football team, Eleven Wise, which he filled with star players and took to the top.

Yeebo says her grandparents' generation would wonder how Ghana, a country rich in natural resources, was so poor after independence. “The sums don't add up,” she explains. “It doesn't make any sense that Ghana would have all these assets that have been stripped and nothing to show for it but widespread environmental degradation, and nothing else. Obviously, the answer is that it was all taken elsewhere to make another place rich.”

As for Blay-Miezah, most people thought that he was only robbing the wealthy in Ghana, the US and the UK, who could afford to lose that money.

“Especially, if he was going to give it away charitably. Talking to people, when I described the basics of what had happened, they were like: 'Well, he was never charged, so good for him.'

“Having said that, there were a lot of people who lost their savings or their livelihoods or worked for him for decades without being paid. The people who invested their time and money with him were by no means universally rich.

“When you look at it that way, you can't really enjoy him screwing over rich people if he was screwing over everybody else as well.

“I think he was incredibly charming and intelligent and also very good at reading and manipulating people.”

Was it possible that even Blay-Miezah came to believe his own story? “I think to run a con as thoroughly as he did, he had to believe some of it. And I think he salted in bits of truth with various versions of his stories.”

In the end, though, Yeebo says, it began to slip out of his control, with other scams involving gold and diamonds “to see if he could just hand over enough money to keep the investors happy long enough”.

She has listened to audio tapes made by Blay-Miezah. “In some of the recordings, he knows it's an absolute scam and says as much, and, then, in some of the more recent recordings, he's like: ‘I can still bring it home.'”

What is clear is that Blay-Miezah, while living the high life with Rolls-Royces and some of the best addresses in New York and London, spent it all.

“His family got left the rights to some of his books and a modest sum of money,” says Yeebo, before making a comparison with how relatives of Ghana's politicians of the day fared. “He clearly hadn't grafted as hard as people in the administration because a lot of their families are rich to this day.”

It bears pointing out that, this month, Ghana’s Minister of Sanitation and Water Resources, Cecilia Abena Dapaah, reported to police that domestic workers had stolen $US1 million and €300,000 from her home, along with handbags worth US$35,000 and US$95,000 in jewellery.

Mrs Abena Dapaah, protesting her innocence, has since resigned. The real story, though, remains: why were such huge quantities of cash in the bedroom of a government minister in the first place?

And, so, decades on from the time of Blay-Miezah, perhaps nothing has really changed.

'Anansi's Gold: The Man Who Swindled The World', by Yepoka Yeebo (Bloomsbury, £20), is available in hardback now