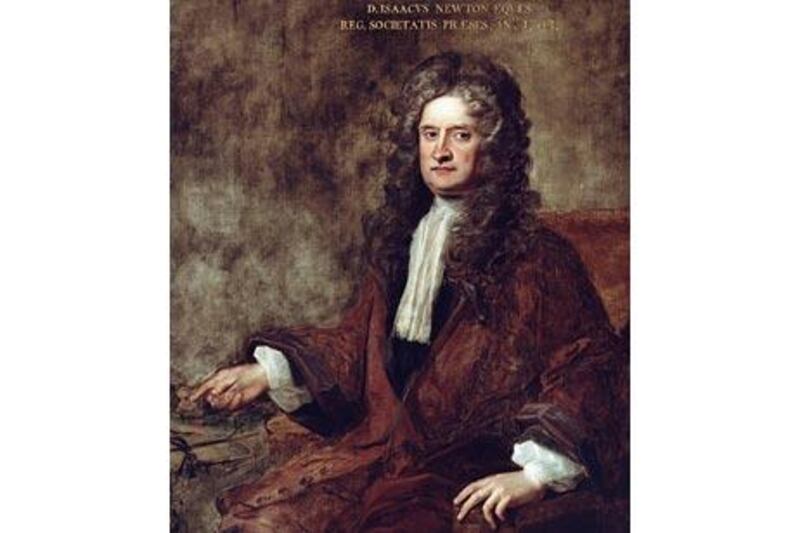

So now we know: the fall of an apple really did inspire Isaac Newton to discover his law of universal gravitation. To great fanfare last week, the Royal Society, Britain's premier scientific institution, made available online images of the manuscript confirming that Newton himself told the celebrated story to a fellow scholar.

As an example of inspired discovery, the story of the falling apple ranks alongside that of Archimedes and his eureka moment in the bath. But unlike that ancient tale, we have the word of Newton - or at least, his contemporary, the archaeologist William Stukeley - attesting to its veracity. The manuscript certainly seems to have impressed some 21st century scholars. As Professor Martin Kemp of the University of Oxford pointed out, the story of the apple has been regarded with mounting suspicion over the years. "We needn't believe that the apple hit his head," he told BBC News, "But sitting in the orchard and seeing the apple fall - was a chance event that got him engaged with something he might have otherwise have shelved."

But as an art historian, Prof Kemp will know that not everything can be taken at face value. And when it comes to the story of one of the greatest discoveries in science, scepticism is certainly merited. For according to some scholars, Newton may have used Stukeley to deny credit to the real discoverer of the law of gravitation. Almost 350 years after the events that supposedly took place in the garden of Newton's childhood home in Lincolnshire, the concept of gravity is still taught according to its original description, whereby "All celestial bodies whatsoever have an attraction or gravitating power towards their own centres". These words date from 1670, but their author is not Newton. They were written by his brilliant contemporary and implacable rival Robert Hooke.

Born seven years before Newton in 1635, Hooke is remembered today chiefly for a dull law connecting the extension of springs to the weight hung from them. Yet his achievements are far more varied. As a pioneer of telescopic astronomy, Hooke discovered the Red Spot of Jupiter, while at the other end of the scale, he designed his own microscopes and coined the word "cell" for the tiny cavities in plant tissue. He also found time to discover the diffraction of light, speculate on the nature of memory - and invented the universal joint, among other things.

Hooke would be a household name today had he not been unlucky enough to suffer the same fate as the composer Joseph Haydn or the playwright Christopher Marlowe, and be eclipsed by an even more gifted contemporary. Yet at least Mozart and Shakespeare had no qualms about acknowledging those who had influenced them. Newton, in contrast, had a pathological personality that made him crave credit and launch hate campaigns against any perceived rival. And chief among these was Hooke.

As fellows of the then newly formed Royal Society, Newton and Hooke regularly exchanged intellectual blows. But Hooke achieved the rare distinction of scoring the occasional knock-out. One such victory arose during Newton's attempt to show that, contrary to appearances, the Earth orbits the Sun. To do this required a way of showing that the Earth spins on its axis, thus creating the illusion that the sun moves around the sky. Newton suggested dropping a ball off a high tower. If the Earth were stationary, the ball would hit the ground directly under the release-point. Yet if it rotated, the landing-point would be shifted slightly. The question was - which way? Common sense suggested the ball would land slightly to the west, having been "left behind" as the Earth rotated eastward. But Newton realised this was not correct: a tower fixed to a spinning Earth shares in its rotation, forcing its tip to move through a greater distance than its base. The ball would thus leave the tower with a tangential speed greater than that of the base, and land slightly to the east. Or so Newton claimed in a letter to Hooke, sketching out the trajectory taken by the ball.

Yet Newton had also made a mistake - as Hooke quickly pointed out. Using his own concepts about falling bodies, he showed that Newton's prediction would only be borne out for a tower on the equator. In the northern hemisphere, the ball would actually land slightly south of east, a fact later confirmed by experiment. A small matter, one might think - but not to Newton, who regarded any form of correction or criticism an unforgivable slur. Historians have shown that he conceived a particular loathing for Hooke, and set about airbrushing him out of history. In the case of gravitation, this required considerable cunning, as letters and manuscripts from the period show that Hooke had come up with the basic features of the phenomenon not later than January 1680. This was several years before the first documentary evidence of Newton's efforts. Unless, that is, one believes the story of the apple.

Newton told this tale to several friends apart from Stukeley just before his death in 1727. Among them was a former colleague, John Conduitt, who dated the incident with the apple to 1666, when Newton was still an undergraduate. If true, this would utterly undermine Hooke's claim to have pioneered the concept of universal gravitation. So what should we believe: Hooke's documented claim, or Newton's uncorroborated anecdote recalled 60 years after the incident supposedly took place? Despite the hoopla generated by the publication of Stukeley's account, many historians will continue to have their doubts - not least because of Newton's refusal to acknowledge the undoubted priority of others in similar cases.

Newton undoubtedly did more than anyone else to lay the foundations of modern science. But when it comes to establishing the originator of the law of gravity, the story of the apple should play second fiddle to the Latin motto of the Royal Society itself: Nullius in Verba - "Take no one's word for it." Robert Matthews is Visiting Reader in Science at Aston University, Birmingham, England