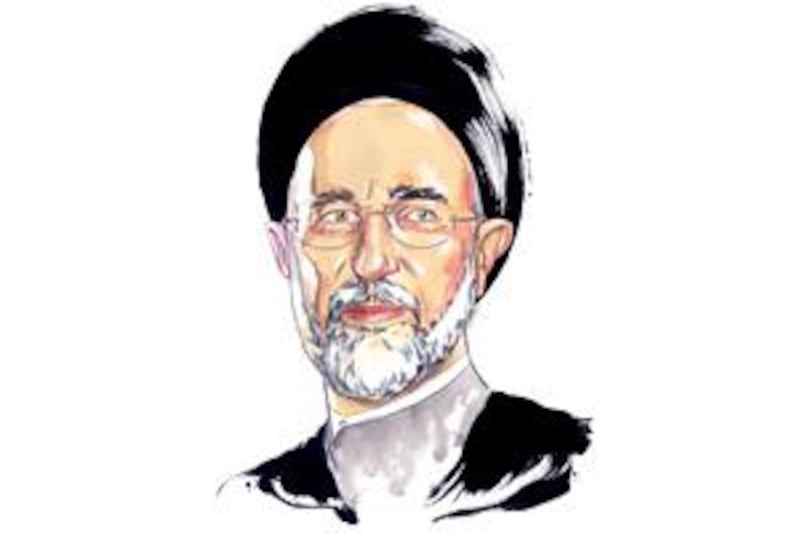

He has not so much thrown his hat into the ring as jumped into the bear pit. Mohammed Khatami, a mild-mannered, softly spoken man, has confirmed he is once again to challenge for the presidency of Iran. He will lock horns with Iran's current president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in June in what promises to be a fiercely competitive, and tightly fought election involving two of the most contrasting political figures in the land. Indeed, if successful, Khatami will be Iran's very own Comeback Kid.

Ending months of speculation, Khatami announced that he would be stepping into the fray last Sunday in a bid to secure a third term in office. President of the Islamic republic from 1997 to 2005 - serving two four-year terms - Khatami was Iran's great reformist, a moderate whose presidency ultimately foundered on the country's powerful conservative resistance. His intention to dislodge the controversial firebrand Ahmadinejad, however, will be welcomed by the West - not least Washington. President Barack Obama, having made a firm commitment to engage Iran with diplomacy, would be keen to deal with the comparatively liberal Khatami, as opposed to the current incumbent who has forged a worldwide reputation as a Holocaust denier and a lover of all things nuclear.

That Khatami wishes to step back into the lion's den is testament to a man who is widely seen in conservative circles as a threat to the ideals of the Islamic revolution, and in the eyes of some reformists as a conviction politician who, nevertheless, bottled it when it mattered most. His wish to take on Ahmadinejad is a bold one, and he will have to use everything at his disposal - from his rich and wide-ranging background to the quietly irresistible urge to better his own modest achievements as president - if he is to re-capture the presidential crown and put Iran back on the road to reform - a platform that saw him win by a landslide in 1997 and again in 2001.

"It has taken a lot of pushing for him to run," says Prof Ali Ansari, an associate fellow in the Middle East and North Africa programme at London's Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. "He was only prepared to do it when he realised the support that he had ? [which includes] his alliance with former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, which is a significant one." Born in the Yazd province of central Iran in 1943, Khatami, the son of a highly regarded Ayatollah, grew up in a strictly orthodox Muslim household. It was a background that helped him reach the third-highest rank - Hojatoleslam - within the Islamic clerical establishment. Yet, through the actions of his father, the young Khatami, the eldest boy of seven children, also gained access to outside views through books and news.

His interest in politics hardened while a student at Isfahan University, one of Iran's leading higher education institutes. Active in the Association of Muslim Students, he worked alongside Ayatollah Khomeini's late son, Ahmed Khomeini, with whom he organised political and religious debates. After gaining a BA in philosophy in 1969, he went on to secure an MA in education at the University of Tehran in 1970, pursuing his love for the written word and western political thought, disciplines that would come to symbolise Khatami as a man of great intellect - a position not shared by his more conservative detractors, and certainly not the mob who were baying for his blood on the 30th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution last Tuesday.

Following a compulsory two-year spell in the Iranian Army, he flirted with journalism, becoming editor-in-chief of the widely read Iranian newspaper the Kayhan Daily, doing so after the overthrow of the Shah and the 1979 Islamic Revolution. By then, he had already spent some time as head of the Hamburg Islamic Centre in Germany, where he studied the work of German philosopher, Jürgen Habermas, whose writings on civil society - explicit in its concept of political and social citizen participation being the bedrock of a functioning democracy - later influenced his own political ideology.

Khatami entered the Iranian political arena in 1980 when he was elected to serve in the Majlis, Iran's new parliament. Then a married man for some six years - he is now a father to two daughters and one son - he was already mastering English, German and Arabic, other than his own native tongue, Farsi. Appointed to the brief of Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance in 1982, Khatami soon demonstrated an ability to ruffle a few feathers when he veered off from the republic's hard-line Islamism. But easing restrictions on the media, art and music were steps too far for many within the political establishment and in 1992 he was forced to resign.

Domestically at least, the die was cast, and after becoming the director of the National Library and an adviser to the then president Rafsanjani, Khatami made a bid for the presidency himself in 1997, winning some 70 per cent of the vote and humiliating his conservative opponent, who was swept away by the then little known cleric's promises of social reform and freedom of expression. Khatami followed up his victory in 1997 with another four years later, again using his understanding of cultural sensibilities and an uncanny ability to tap into the public mood.

"He didn't just charm me, he charmed the whole country - and that's why he was elected in 1997 in that stunning victory," said Elaine Sciolino, a writer on Iran for The New York Times, speaking to the BBC before Khatami's election win in 2001. "This is a man who went on public buses. He's the kind of baby-kissing politician we're used to here in the United States. He rolled up his sleeves publicly and gave blood. He tries to straddle the world of Islam and Islamic clericalism, and the world of the people."

His presidency essentially hit the buffers when his desire for change was blocked by the nation's conservative institutions, leading to mass student demonstrations in 2003. But in both appointing the country's first woman to the cabinet and becoming the first Iranian head of state to visit Europe since the revolution, Khatami made a statement of intent, which, by symbolism alone, captured the public imagination - at least for a while. Indeed, the widespread belief that the middle-ranking cleric's terms in office were the least effective in Iran's post-revolutionist history disregards the harsh political climate in which he was forced to operate - one, which weighted against him, partly explained his inability to follow through on many of his chosen reforms.

"My policies might not have borne any fruit, but I still believe that they were and are useful," he told The Washington Post on Monday, defending his record in office. It is with this reformist agenda that Khatami will take on Ahmadinejad in the political bear pit this summer. Khatami will need to reinvigorate his base - the country's professional class and student body, but also the aspiring working classes who, so taken with Ahmadinejad's promises of a better life in 2005, have since found their wants unfulfilled.

Analysts, including the US-Iranian expert Trita Parsi, have highlighted the contrast between Khatami's perceived lack of derring-do with the current president's brio, suggesting that the only way the 65-year-old Khatami can win over Iran's voting public is by adopting some of his adversaries' boldness. Yet, boldness should not be confused with confrontation, and, in a foreign policy sense at least, confrontation has almost been Ahmadinejad's raison d'être. Khatami who, in contrast to his more populist opponent, heartily subscribes to the republican element of the Islamic republic, will require a little extra inner steel and outward drive and gusto if elected to an unprecedented third-term, yet he is no stranger to the rough and tumble of politics, and knows what it takes to pull off explosive election victories.

Although one cannot expect too much change in the foreign policy department - and certainly not straight away - if Khatami succeeds in unseating Ahmadinejah, there is one major diplomatic row - other than the nuclear one where Khatami is seen as a moderate - which has had western leaders choking into their soup bowls for the past four years, that will almost certainly be consigned to the scrap-heap.

"Khatami has already said that he accepts the Holocaust as an historical fact and that it is a tragedy that should be recognised," says Prof Ansari. "He is very popular among the Iranian Jewish community, who see him as a very sympathetic figure." If Khatami should triumph in June, such intimations would, in the context of the decidedly frosty relationship between Tehran and Washington, provide for at least one area of mutual agreement.

* The National