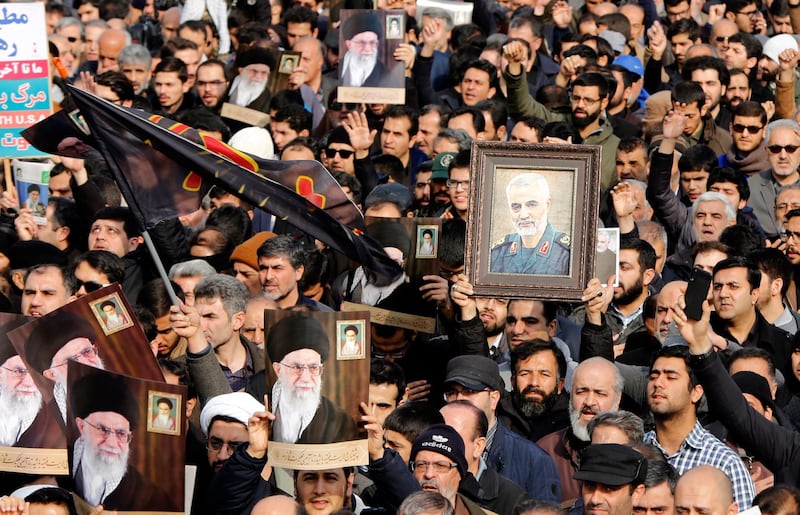

The killing of Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani will have a long-lasting impact across the Middle East region, nowhere more than in Iraq.

His successor, Esmail Qaani, was named within hours but Suleimani is not one to be replaced so easily.

Personal relationships cultivated with leaders of key militias, from Lebanon’s Hezbollah Hassan Nasrallah to the head of the Badr Brigades, Hadi Al Ameri, made Suleimani a lynchpin of Iran’s role in directing militias around the Arab world.

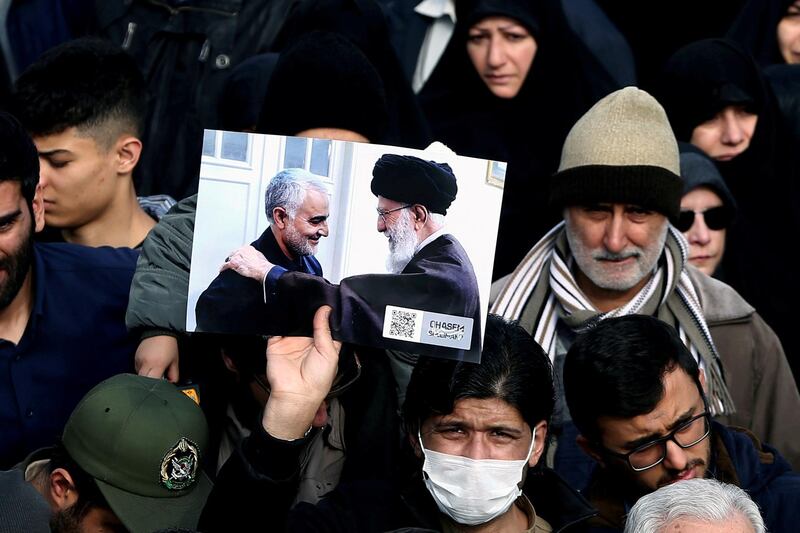

Suleimani’s closeness to Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei developed over decades as he rose in the ranks of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and was critical to Iranian expansionism.

Khamenei declared Suleimani a “living martyr” for a reason. Suleimani not only expected the status but wanted it in order to be lionised in death and thus act as a rallying point in future.

His influence over the key political leaders in Iraq was demonstrated by his ease of movement in the country, especially in the last couple of years.

It had led many to believe that he was invincible in the country and could ultimately call the shots. His demise will not only impact Iran, but will play out in the calculations of friends and foes in Iraq.

The tone of the third decade of this century in the Middle East has been set by the surprise American attack on Friday morning. Also removed was the main architect of militia control in Iraq, Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis.

There can be no doubt that this is the start of a new era in the region and its repercussions will be felt for years. Confrontation between the US and Iran may not develop in a traditional military sense but it has entered a different phase.

Whether Suleimani’s death weakens Iran’s ability to enforce its agenda in the region or propels Iran to act even more decisively is yet to be seen. Either Iran will take the hit, sit on the backfoot and make concessions, or it will feel a need to retaliate on a large scale to prove it won't give up any of its regional political and military gains.

Equally Washington could decide to de-escalate as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced hours after the attack, or choose to see the confrontation through.

There is no longer a proxy war, even if proxies will be used to fight the battles.

What is certain is that the calculations will take years to play out and the impact will likely dominate this decade in the region.

The first decade of this century for the region was defined in large part by the attacks of 11 September 2001 and the consequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The second decade was framed by the uprisings that began in Tunisia and Egypt but then quickly spiralled into violence in Syria, Libya and beyond. The consequences are still unfolding.

The dramatic events of both decades led to a rise of non-state actors, including Al Qaeda affiliated groupings as well as militias trained and commanded by Suleimani and the IRGC.

Washington maintained its fight against extremist Islamist groups, beginning with the war on the Taliban in Afghanistan and culminating with the killing of ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi in Syria last October.

Iran meanwhile was largely able to expand its reach unchecked. No-one symbolised that reach more than Suleimani criss-crossing through Iraq and Syria imposing Tehran’s agenda and making a show of it.

The act of “exporting of the revolution” was considered by the Iranian regime as essential to its existence and was increasingly orchestrated by Suleimani.

The new leader of the Quds Force, Qaani, will now seek to pick up this mantle. As deputy of the elite special forces, Qaani was responsible for Iran’s activities in Afghanistan and oversaw the “Fatemiyoun” brigade that fought in Syria to prop up the regime of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad.

Qaani famously said in 2017 that “Fatemiyoun is a new culture — a collection of brave men who do not see boundaries and borders” in realising Iran’s ideology on the ground.

The fact that a direct confrontation between the US and Iran took so long is in itself a wonder.

Iran has not ceased calling for “death to America” for 40 years while America for its part branded Iran the “number one state sponsor of terrorism”.

Iraq was the arena for a contradictory phase of US-Iranian cooperation even as each country wanted to take Iraq in completely opposite directions.

Iran wanted to pull Iraq into its sphere of “revolution” and “resistance” while the US saw Baghdad as the centre of a new “democratic” region.

The brief spell of cooperation in fighting ISIS and supporting mutual allies in Baghdad embodied the contradictions of the Middle East region and could not have lasted. The killing of Suleimani in Baghdad put an end to those contradictions.

Iraq will have to chose in which direction it wants to go and that could be the defining struggle of the coming decade.