It is so natural, we never give it a second thought. To pick up a phone and instantly speak to someone in the next street or town or even a country thousands of kilometres away. Not too long ago, this was far from the case.

As the UAE entered its third year since unification, the seven emirates still seemed like foreign countries when it came to telephone calls. To reach someone in Dubai from Abu Dhabi, or vice versa, meant a complicated process of speaking to an operator, who would place the call. This tiresome routine applied to everyone, whether a sheikh or a salesman.

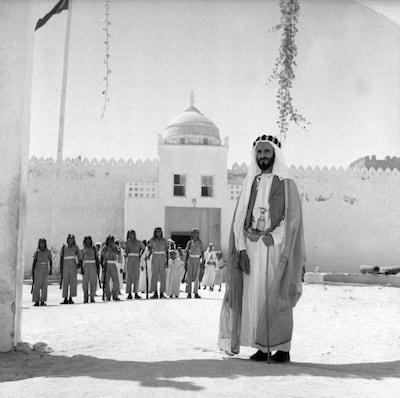

All this changed on the last day of January 1974 when UAE Founding Father, the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, picked up the phone in his office and dialled Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed, Ruler of Dubai.

From that day, 50 years ago, anyone in Abu Dhabi could phone someone in Dubai. Within five days, anyone in Ajman, Umm Al Quwain and Sharjah could do the same. Ras Al Khaimah, whose telephone exchange at the time had only 750 lines, would follow later, with Fujairah opening its first telephone exchange in 1979.

It was the simplest of things, but one with enormous significance. It signalled that the seven emirates had become truly connected. At a time when the UAE’s road system was still under development, when Dubai and Abu Dhabi were connected only by a single lane of tarmac, a fast and efficient electronic motorway now existed.

Even more extraordinary is the fact that barely a decade earlier, phones in what was now the UAE did not exist at all. Dubai was the first, with Sheikh Rashid watching the first call placed by a British official on July 29, 1960. Two years later, the phones began ringing in Abu Dhabi.

By then more than 80 years had passed since the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell, a communication system long taken for granted in much of the rest of the world.

The long delay was largely the result of Britain’s grip on the region, where it controlled foreign affairs – and investment – thorough a series of 19th century treaties.

In the 1950s and early 60s, it meant British companies were first in line when it came to building infrastructure projects. In the case of telephones, these companies decided the emirates were not worth the expense or trouble.

“The picture is rather gloomy,” a report to London began in May 1954. Bernard Burrows, the British political resident in Bahrain, the base of UK operations in the Gulf, had been examining the likelihood of expanding phone services in the region.

His concerns were political as much as practical. “The provision of telephone and telegraph services has come to be part of the British connexion with the States and if the services provided are unsatisfactory or are withdrawn, this will represent a weakening in our position in the Gulf,” he wrote to his masters in Whitehall.

Phone services in the Arabian Gulf were operated by Cable and Wireless, a telecoms company nationalised by Britain’s socialist government in 1947 and which held a monopoly of services across the British Empire.

Cable and Wireless had looked at Dubai and Sharjah but decided the number of potential local subscribers was too low and the cost uneconomic. The company did not even consider Abu Dhabi, which in the 1950s had a population estimated at fewer than 3,000.

But they had not reckoned with Sheikh Rashid. A moderniser, he had already dredged the Creek to allow bigger ships to trade through Dubai. Electricity was next, creating demand for a whole range of consumer products, from air conditioners to refrigerators.

A telephone system was the obvious next step. Cable and Wireless was persuaded to give up its rights to Dubai and a new joint company was set up with International Aeradio Ltd (IAL), another British firm better known for its air-traffic control systems and which was also building the city’s new airport.

IAL would hold a minority stake in the new Dubai Telephone Company with the emirate holding a 51 per cent of shares. The honour of inaugurating the first telephone was given to Donald Hawley, British political agent in Dubai, the equivalent to an ambassador.

“The advent of telephones has made a tremendous difference to the way in which business is conducted in Dubai,” Hawley wrote home later that year.

With telephones came the first phone book, containing only 30 pages in 1961, with adverts, some hand-drawn, for Land Rovers, typewriters and radios. It listed the home numbers of 275 subscribers, including many of Dubai’s most prominent people.

By 1962, the number of subscribers had grown to more than 500, and to 850 the following year. By the end of the decade this had exceeded 2,000, with services extended to Sharjah and Ras Al Khaimah.

What Dubai had, Abu Dhabi quickly wanted, too. Large quantities of oil had been discovered in the emirate in 1958 and the local economy was exploding.

Like Dubai, Abu Dhabi was in theory a concession of Cable and Wireless, but this was of little concern to the Ruler at the time, Sheikh Shakhbout bin Sultan, who summoned IAL and offered them a 51 per cent in the new Abu Dhabi Telephone Company with rest to be held by himself and local partners.

Alan Ashmole arrived in Abu Dhabi in 1962 to work for the British Bank of the Middle East, now HSBC. “One of the problems of working there was there was no telephone system,” he notes in his memoir Sand, Oil and Dollars.

By the following year this had changed, but: “Even when this was installed later, there was no direct telephone communication to the outside world. The oil company had radio telephone communications and in case of an emergency this was the only way to contact the outside world quickly.”

An early decision made by Sheikh Zayed, when he became Ruler of Abu Dhabi in 1966, was to fully nationalist the emirate’s telephone company. Following the formation of the UAE in December 1971, a new national telephone firm was created, initially called Emirtel, and later renamed as the more familiar Etisalat.

The country was divided into different dialling codes, with 02 for Abu Dhabi, 03 for Al Ain, 04 for Dubai, 06 for Sharjah, Ajman and Umm Al Quwain, 07 for Ras Al Khaimah and 09 for Fujairah.

Etisalat introduced mobile phones in 1987, with the relatively slimline NEC TR5E1000-9A and a price tag of Dh8,500 ($2,314). An early handset was acquired by Mohammad Al Fahim, whose father had been one of the first with a desk phone.

It is now an exhibit in his private museum. “It's very heavy, you cannot carry it in your pocket, and talk time would be about 45 minutes. Then you would have to recharge it for about two hours. So you used it only when necessary,’ he told The National in an earlier interview.

Today, it is estimated there are close to 20 million smartphones in the country, or about two for every man, woman and child, one of the highest percentages in the world.

Like the record company executive who turned down the Beatles, or the publishers who rejected JK Rowling and Harry Potter, that decision by Cable and Wireless to pass on Abu Dhabi and Dubai may well have been once of the worst business decisions in history.