A Syrian friend of mine complained, rightly, that both sides in the country's civil war have had a hand in destroying his house.

His summer villa was perched in a hillside village between Damascus and the Lebanese border. Armed militants broke in and fired, from the roof, at an army post. Soldiers responded with mortars and machine-gun fire. The rebels ran away.

No one won, and the house was wrecked.

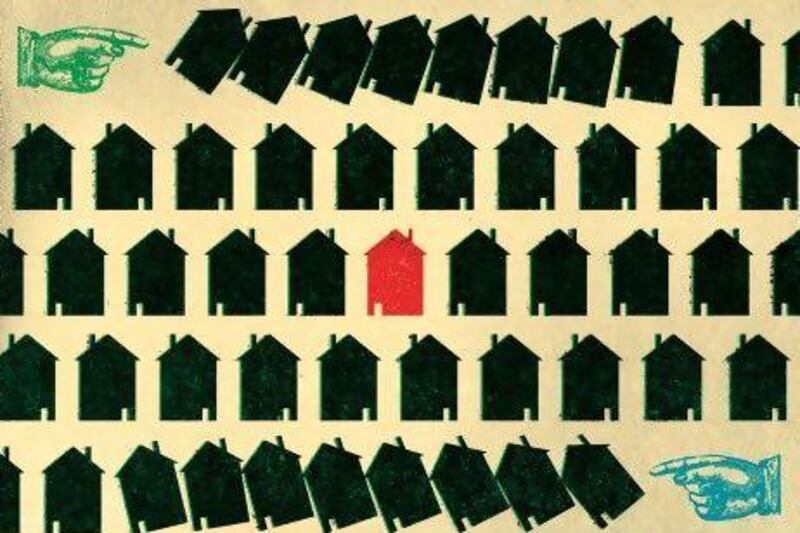

If a single image sums up the war in Syria, my friend's house does the job. Neither the troops nor the insurgents gave a damn about him or his house, and it's not clear how much either cares about the country, either.

When 15 schoolchildren wrote the first dissident slogans on walls in the border town of Dera'a in February 2011, neither they nor the policemen who tortured them foresaw where their actions would lead.

The children's courage emboldened their elders to march through the streets of Damascus, Homs, Idlib and other cities to voice discontent, as they never had before.

This was not a violent insurrection by religious obscurantists as in 1982, when the Muslim Brotherhood took up arms in Hama and Aleppo without consulting their inhabitants. Rather, this was a popular movement that was finding its way, learning from its mistakes and winning support.

Some backing came from foreign powers, which assisted the transformation of a popular and non-violent struggle into an armed uprising more like Hama in 1982 than Dera'a in 2011.

The outsiders, with their own objectives, provided rifles, ammunition, communications equipment, military vehicles and combat advice to young men who lacked the discipline and patience for a long-term, non-violent and democratic struggle.

The contending forces met head-on in Homs, whose citizens lost their houses and the previous harmony among communities.

No one envisaged the consequences of this conflict when it began. About 20,000 people, by most estimates, have died. More than that number are maimed, scarred or blinded for life. At least 78,000 have fled to neighbouring states, according to figures published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

One NGO, Refugees International, estimates that another million people have been driven from their homes to other corners of Syria. Some have fled more than once, as the violence spread.

For many refugees, the rallying cries of the regime and of the armed opposition ring equally hollow. Some have been sheltered in tented camps in Turkey and Jordan, while others have found lodging with friends or relations in Lebanon.

Syrians, who earned an average of Dh1,000 a month when they had jobs, are paying rents of Dh365 a month or more to sleep in Bekaa Valley car parks or Dh1,850 for space above a garage. Others sleep rough and beg for sustenance in the streets of Lebanese cities.

The exiled Syrians are learning what Palestinians have known since 1948: refugee existence is demeaning, cruel and crippling.

Palestinian refugees, 486,000 of whom are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in nine camps in Syria, are suffering more now than at any time in their 64 stateless years.

They are trapped, not permitted by Israel to return home and unable to obtain visas to most other countries. They are also caught between the regime's and the Free Syrian Army's rival demands on their loyalty.

Rebels took positions in Damascus's largest refugee camp, Yarmouk, provoking a predictable army response. Shells hit Palestinian dwellings, frightening many refugees away to Lebanon, which offers neither work nor hope.

Young Palestinians conscripted into the government's all-Palestinian brigade, the Palestine Liberation Army, have been attacked. When someone murdered about 20 of them on a bus near Aleppo in July, the regime and the Free Syrian Army blamed each other - although why the regime would kill conscripts in its own army is hard to explain.

No one is untouched. Nearly 150,000 Armenians are caught between the contending forces. Some belong to families that have lived in Syria for centuries, but the majority of them descend from survivors of the Turkish massacres of more than one million Armenians around the First World War.

Several hundred have reportedly left for Armenia. Those who depart are leaving behind their churches, some dating to the early years of Christianity, as well as schools, clubs and other institutions around which their comfortable lives revolved.

Criminals are looting Syria's archaeological heritage, as they did in Iraq. Interpol has warned of "imminent threats" to Syria's Sumerian, Hittite, Greek, Arab, Roman, Crusader and Ottoman treasures. Unesco appealed for protection of World Heritage Sites, and rebels have moved on the Crusaders' Crac des Chevaliers and Aleppo's Citadel. The Global Heritage Fund documented at least 16 historical venues "known to have been affected by shelling".

In the meantime, Syria's Kurds, with Bashar Al Assad's blessing, have assumed control of their own affairs in the north-east, along the Turkish border.

This example of Kurdish autonomy upsets Turkey as much as the fact that the largest Kurdish group, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), is allied with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) that is launching armed attacks in south-east Turkey.

Mr Al Assad's message to the Turks is perfectly clear: if you send my citizens to attack me, I can do just the same thing to you.

Now the kidnappings have begun. Salafists allied to the armed opposition have kidnapped a number of western journalists, and other militias have taken 48 Iranians.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry wrote to the US, through Swiss intermediaries, that "because of the United States' manifest support of terrorist groups and the dispatch of weapons to Syria, the United States is responsible for the lives of the 48 Iranian pilgrims abducted in Damascus".

This was very like the message the Iranians sent in 1982, when pro-Israeli Christian gunmen kidnapped four of its embassy personnel in Lebanon. That time, the retaliation came with the kidnapping of almost 100 western nationals over the follow=ing eight years.

Rather than contain this mayhem, which is already backfiring on Turkey and will undoubtedly do the same to the United States, Washington and Moscow are encouraging their clients to fight rather than negotiate.

Syria is the primary victim in all of this, but it will not be alone.

Charles Glass is the author of several books on the Middle East, including Tribes with Flags and The Northern Front: An Iraq War Diary. He is also a publisher under the London imprint Charles Glass Books.