The news from Down Under reached New York on Christmas night, speeding there in just 24 minutes through the modern miracle of land and sea cables. Most Americans got the word the next morning in their newspapers: A black man was the heavyweight champion of the world. The year 1908 was drawing to an end, and Jack Johnson reigned supreme. After years of chasing reluctant white champions for a fight, he gave Tommy Burns a beating in Australia that reverberated half a world away.

Almost immediately, a search began to find someone to wrest the crown from his freshly shaved head. It settled on Jim Jeffries, the former champion who had retired unbeaten to his California farm four years earlier. "Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson's face," Jack London, the author, wrote. It would not be easy. Jeffries had ballooned to more than 135kg and had little interest in fighting again. He had even less interest in bearing the weight of an entire race against a champion who flouted society's mores with his love of fast cars and white women.

Jeffries also knew something most of white America refused to acknowledge: Johnson possessed perhaps the best skills of any heavyweight since the Marquess of Queensbury rules turned boxing into a somewhat respectable sport. Still, the drumbeat intensified. Promoters dangled riches in front of Jeffries, and newspapers campaigned for him to regain the title for his race. Finally, Jeffries acquiesced. They would meet on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada, in a scheduled 45-rounder that was immediately dubbed the Fight of the Century.

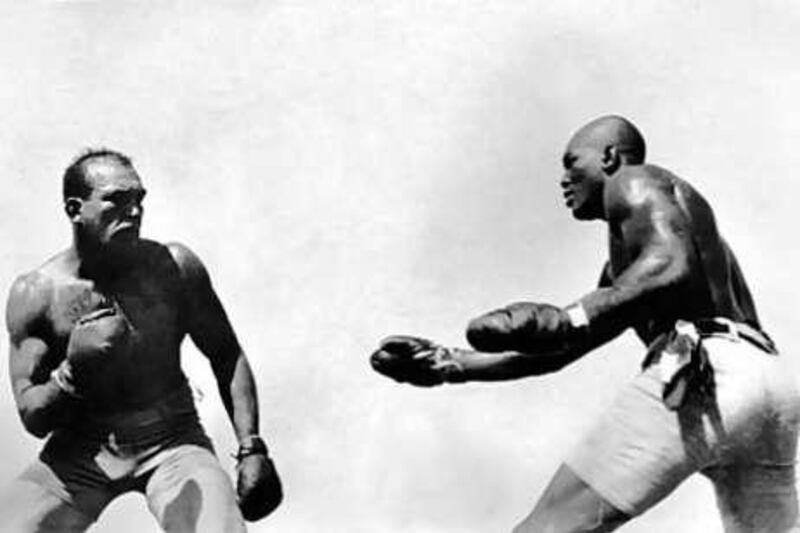

The day of the fight was a hot one, and there was no shade in the arena. The arena, built in just two weeks, had room for 18,000 spectators. Ticket prices ranged from $10 (Dh36.7) to $50 at ringside. Another 2,000 people paid $5 for standing-room-only. With racial tensions on edge, no liquor was allowed in the arena. No guns either. The fight started late, causing rumours to sweep through the crowd that Johnson had chickened out. It finally went off at 2.44pm, with both men smiling at each other as they made their way to the centre of the ring, though Jeffries refused to shake Johnson's hand.

It did not take long to realise that Jeffries would have trouble against the younger champion. Jim Corbett, a former champion, roamed about at ringside shouting insults at Johnson and cheering on Jeffries, but Johnson was too good. By the 13th round, the challenger's nose was broken, his eyes were nearly swollen shut and he was gasping for air. The end came in the 15th round when Jeffries, his face puffy and bloody, went down for the first time in his career from a flurry of punches. He was able to get up at the count of nine, but Johnson sent him through the ropes with a right hand to the jaw. Reporters had to help him back into the ring.

Jeffries staggered across the canvas where a combination put him down for the last time. His team jumped into the ring to stop the fight, even though there was no doubt Jeffries was not getting up. John L Sullivan wrote for The New York Times that there had never been a championship contest so one-sided. Even more impressive, he said, was how it was done. "He played fairly at all times and fought fairly," he said.

Things got ugly as news flashed around the country that a black boxer had not only defeated the "great white hope" but had given him a beating in the process. The next day The Chicago Daily Tribune counted at least 11 dead around the country. White America was unsettled with the realisation that not only was there a black heavyweight champion, but one with the skills to be champion a long time. It hardly mattered that outside the ring, Johnson was a man of culture who was conversant in several languages, and often read novels in French. They saw only the public side of Johnson, that of a high-flying flamboyant champion who refused to live by the unwritten rules of society.

Johnson would not fight for another two years and, soon afterward, was arrested on charges of violating the Mann Act by transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes. He was convicted and sentenced to a year and a day in prison, but skipped bail and left the country. Never repentant about his ways, Johnson was still an attraction in his later years, fighting sporadically and putting on exhibitions. Jeffries, meanwhile, returned to the alfalfa ranch and trained fighters until his death in 1953.

It would be 27 more years before Joe Louis beat James Braddock and a black man became heavyweight champion again. * AP